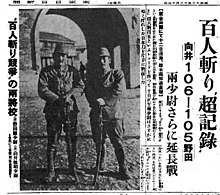

| The competition was reported in a Tokyo newspaper, and it was clear that two soldiers of the Japanese Imperial Army were partaking with extraordinary enthusiasm. ‘Incredible record in the contest to behead 100 people!’ screamed the headline with gruesome relish. ‘Mukai 106 - 105 Noda - Both 2nd Lieutenants go into extra innings.’ According to the report, two junior officers had a wager to see who could decapitate 100 Chinese soldiers first.

Brutal history: A scene from the new film City Of Life And Death. But they hit their target so quickly that they decided to set a new goal of 150. The date was December 13, 1937, and the Japanese Imperial Army was in the process of ruthlessly conquering Nanking, which was then the capital of China. Ten years later, the story came to the attention of the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal. Second Lieutenants Mukai and Noda were extradited from Japan and executed. Hitler and Stalin may have killed millions more by gassing or starving, but the sheer velocity of the Nanking massacre is what takes the breath away. In just six weeks, hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians were slaughtered by the Imperial Army in and around Nanking. Quite how many hundreds of thousands has never been agreed. China claims 300,000. The official tribunal put the death toll at 200,000. The more conservative elements of Japanese society have always argued that the figures were wildly exaggerated. Where some revised it down to 100,000, or even less, others went so far as to question whether the killings took place at all. You might imagine that nearly three-quarters of a century on, none of this matters any more. But the massacre is a historical event that refuses to be consigned to the past. To many Chinese and Japanese alike, it still matters intensely. While the argument about massaging the figures and the extent of Japanese guilt continues to simmer, the smoking bonfire of the conflict cannot be extinguished. And while that remains the case, relations between two of the world’s biggest and most important economies will never be normalised. This month not one but two new films about Nanking are out in British cinemas. Watching them is a brutalising experience. The first, called City Of War: The Story Of John Rabe, tells the story of a German resident and Nazi party leader in Nanking who set up a safety zone in the city. Like Oskar Schindler, whose story was told in Schindler’s List, Rabe helped to save the lives of thousands of civilians.

Barbarity: 20,000 Chinese women were raped by Japanese soldiers in Nanking during the 1930sCity Of War includes a reenactment of the beheading contest. But for the sheer scope of violence, it finishes in second place to the other film, City Of Life And Death. Though Rabe is featured in this film, too, the main characters are Chinese and Japanese. City Of Life And Death is one of the most unsparing films about the horrors of war ever made. There are mass shootings and executions, crowds indiscriminately mown down and men shot at the stake by firing squad. Victims dig their own mass graves. A barn full of hundreds of screaming prisoners is locked and incinerated. The carnage is indescribable. In the charnel house that is Nanking, Japanese soldiers drunk on death kill like addicts getting a fix. Nor does the film flinch in visiting the other horrific aspect of Japanese crimes: the rape of 20,000 women, most of whom were then killed. In one scene a woman lies numbed, as if in a self-protecting coma, while a group of eager soldiers queue up. A few frames later, her naked body is tossed on to a cart already loaded with female corpses. The viewer is at least spared the uniquely ghastly method of ritualised mutilation, which was to stab the rape victim afterwards with bayonets or bamboo. Nor is there any overt reference to another aspect of the Imperial Army’s sadism: the random slaughter of children. Babies were speared on bayonets. Pregnant women were raped. One was raped at full-term, then stabbed in her womb. While China continues to refer to this bloodstained moment in Chinese history as the Nanking Massacre or the Rape of Nanking, in Japan they call it the Nanking Incident, as if it’s some slightly embarrassing faux pas committed by a drunken uncle a few years back. So what was the background to such atrocities? It was in 1931 that Japan invaded Manchuria. The trigger was a bomb attack on a stretch of railway on the Chinese coast leased by Japan. The bomb did little damage, feeding speculation that it was planted by the Japanese themselves.

Civilians were 'shot down like the hunting of rabbits in the streets' by soldiers . However, the Imperial Army promptly occupied several cities along hundreds of miles of coastline. Resistance from the Chinese began only once the communists and nationalists buried their differences and agreed to unite. That was in 1937. As a result, the Japanese army took huge casualties and several bloody months to subdue Shanghai. Nanking was next. The Chinese leadership anticipated a heavy defeat and withdrew the majority of their troops. A rump of 100,000 mostly untrained soldiers remained, many of whom later fled, forcing civilians to hand over their clothes to them before they left. Civilians were prevented from fleeing by the blockage of the roads and port. The conditions could not have been more perfectly created for what happened next. And it’s not difficult to see why, for many, this is a wound that stubbornly refuses to heal. According to Japanese historians and politicians, the deaths, such as they were, were a legitimate consequence of war. Yes, punishment was threatened for soldiers who ‘dishonour the Japanese army’. But according to a journalist travelling with the army, the rapid advance on Nanking was fuelled by ‘the tacit consent among the officers and men that they could loot and rape as they wish’. A small number of remaining Westerners, mostly Americans, were able to keep a record of events as they unfolded. Among them was a rookie reporter for the New York Times. At the waterfront he saw ‘a group of smoking, chattering Japanese officers overseeing the massacring of a battalion of Chinese captured troops. They were marching about in groups of about 15, machine-gunning them’.In just ten minutes he saw 200 prisoners meet their deaths. The Japanese were evidently enjoying themselves. The Japanese government had agreed to attack only those parts of the city containing Chinese troops. Civilians fled to the Nanking safety zone, but it turned out to be no guarantee of salvation. John Magee, an American missionary who had lived in Nanking for more than 20 years, witnessed civilians ‘shot down like the hunting of rabbits in the streets’. He captured on film examples of Japanese crimes, including the murder in one house of 12 residents, from grandparents to babies.

'We stabbed and killed them, all three - like potatoes in a skewer,' a Japanese soldier recalled The females, including teenagers, were raped and horrifically mutilated. ‘The slaughter of civilians is appalling,’ wrote Robert Wilson, a surgeon in the University Hospital, in a letter home on December 15. ‘I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief. ‘Two bayoneted corpses are the only survivors of seven street cleaners who were sitting in their headquarters when Japanese soldiers came in without warning or reason and killed five of their number and wounded the two that found their way to the hospital.’ ‘Rape! Rape! Rape!’ wrote the Reverend James McCallum. ‘We estimate at least 1,000 cases a night, and many by day. In case of resistance or anything that seems like disapproval, there is a bayonet stab or a bullet.’ John Rabe reported the same figure: a tariff of 1,000 rape victims in one night, including one woman behind his garden wall. She was raped, then stabbed in the neck. ‘You hear nothing but rape,’ he wrote. ‘If husbands or brothers intervene, they’re shot. What you hear and see on all sides is the brutality and bestiality of the Japanese soldiers.’ A Chinese witness recalled a pregnant woman being raped, then stabbed. ‘She gave a final scream as her stomach was slashed open. Then the soldier stabbed the unborn child and tossed it aside.’ It’s not as if the only witness accounts were from neutrals or victims. A Japanese soldier called Azuma Shiro later recalled capturing nearly 40 old people and children, including one woman with a child in each arm. ‘We stabbed and killed them, all three - like potatoes in a skewer. I thought then that it’s been only one month since I left home ... and 30 days later I was killing people without remorse.’ An English language teacher called Minnie Vautrin kept a diary. ‘There probably is no crime that has not been committed in this city today,’ she wrote on December 16. ‘Thirty girls were taken from the language school last night, and today I have heard scores of heartbreaking stories of girls who were taken from their homes last night - one of the girls was but 12 years old.’ Her diary refers to scenes ‘that a lifetime will not erase from my memory’.

Japanese soldiers raped up to 1,000 women a day - anyone who resisted was stabbed or shot. After a breakdown, she returned home in 1940 and a year later committed suicide. Prophetically, she wrote: ‘How many thousands were mowed down by guns or bayoneted we shall probably never know.’ And that is the nub of the argument between China and Japan that continues to this day. If anything, in the past decade it has intensified. Where Germany has long since admitted its guilt for wartime genocide and made Holocaust denial a crime, Japan has passed no equivalent legislation. Ten years ago, a Nanking survivor - who was eight when she saw seven family members murdered and heard her mother and sister being raped and then killed - sued two Japanese authors and their publisher for allegedly distorting the truth about the event. Hiding under a quilt, she had been stabbed three times. She bore witness at the war crimes tribunal in 1945. And yet one of the writers, a professor, said in an interview that there was ‘no record’ proving the massacre had taken place. For Japanese schoolchildren there was, indeed, very little record. In Japan, history lessons have tended to ignore the atrocities committed by the Imperial Army. Textbooks tell their own version of the truth while Takami Eto, a senior Japanese politician, described the Nanking massacre as ‘a big lie’. For much of the past decade, China refused to hold bilateral talks with Japan because its then prime minister kept visiting the shrine memorial to Japan’s war dead in Tokyo. Among the dead are several convicted war criminals held responsible for the Nanking massacre. Now we have the latest instalment in this toxic saga with the release of City Of Life And Death. It is an immensely powerful film, brilliantly directed by Lu Chuan, a young star of the Chinese cinema. When the film opened last April in China, it caused a storm of protest. On his official blog, Lu received a number of death threats. The interesting thing about these violent responses is that they did not come from Japan. They came from China. Lu’s crime, in the eyes of some, has been to humanise the enemy. One Japanese soldier is seen wandering through the scenes of horror looking profoundly shaken by the senseless acts of savagery perpetrated by his compatriots. The idea that a Japanese soldier might have feelings turns out to be deeply shocking to some Chinese. Some detractors called for City Of Life And Death to be deleted from the history of Chinese cinema. It was not included in the official list of films celebrating the 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. It was also withdrawn at the last minute from the Chinese equivalent of the Baftas. Despite the furore, City Of Life And Death made $20million (£13.1million) in its first two weeks. The film has been seen elsewhere in the world. Two weeks ago, it won best movie at the Asian Film Awards. But however much it humanises the enemy, there is one country in Asia where there is no immediate prospect of a release.

| |

n August 1937, the Japanese army invaded Shanghai where they met strong resistance and suffered heavy casualties. The battle was bloody as both sides faced attrition in urban hand-to-hand combat. By mid-November the Japanese had captured Shanghai with the help of naval bombardment. The General Staff Headquarters in Tokyo initially decided not to expand the war due to heavy casualties and low morale of the troops. However, on December 1, headquarters ordered the Central China Area Army and the 10th Army to capture Nanking, then-capital of the Republic of China. Relocation of the capital After losing the Battle of Shanghai, Chiang Kai-shek knew that the fall of Nanking would simply be a matter of time. He and his staff realized that they could not risk the annihilation of their elite troops in a symbolic but hopeless defense of the capital. In order to preserve the army for future battles, most of them were withdrawn. Chiang's strategy was to follow the suggestion of his German advisers to draw the Japanese army deep into China utilizing China's vast territory as a defensive strength. Chiang planned to fight a protracted war of attrition by wearing down the Japanese in the hinterland of China.[13] Leaving General Tang Shengzhi in charge of the city for the Battle of Nanking, Chiang and many of his advisors flew to Wuhan, where they stayed until it was attacked in 1938. Strategy for the defense of Nanking In a press release to foreign reporters, Tang Shengzhi announced the city would not surrender and would fight to the death. Tang gathered about 100,000 soldiers, largely untrained, including Chinese troops who had participated in the Battle of Shanghai. To prevent civilians from fleeing the city, he ordered troops to guard the port, as instructed by Chiang Kai-shek. The defense force blocked roads, destroyed boats, and burnt nearby villages, preventing widespread evacuation. The Chinese government left for relocation on December 1, and the president left on December 7, leaving the fate of Nanking to an International Committee led by John Rabe. The defense plan fell apart quickly. Those defending the city encountered Chinese troops fleeing from previous defeats such as the Battle of Shanghai, running from the advancing Japanese army. This did nothing to help the morale of the defenders, many of whom were killed during the defense of the city and subsequent Japanese occupation. Approach of the Imperial Japanese Army Japanese war crimes on the march to Nanking

An article on the "Contest to kill 100 people using a sword" published in theTokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun. The headline reads, "'Incredible Record' (in the Contest to Cut Down 100 People) —Mukai 106 – 105 Noda—Both 2nd Lieutenants Go Into Extra Innings".[14]

Sword used in the "contest" on display at the Republic of China Armed Forces Museum in Taipei, Taiwan Although the Nanking Massacre is generally described as having occurred over a six-week period after the fall of Nanking, the crimes committed by the Japanese army were not limited to that period. Many atrocities were reported to have been committed as the Japanese army advanced from Shanghai to Nanking. According to one Japanese journalist embedded with Imperial forces at the time, "The reason that the [10th Army] is advancing to Nanking quite rapidly is due to the tacit consent among the officers and men that they could loot and rape as they wish."Prince Asaka appointed as commander Prince Yasuhiko Asaka in 1940

Head of a Chinese man beheaded by Japanese is wedged in a barricade near Nanking just before the fall of the city.[28] In a memorandum for the palace rolls, Hirohito had singled Prince Asaka Yasuhiko out for censure as the one imperial kinsman whose attitude was "not good." He assigned Asaka to Nanking as an opportunity to make amends.[29] On December 5, Asaka left Tokyo by plane and arrived at the front three days later. Asaka met with division commanders, lieutenant-generals Kesago Nakajima and Heisuke Yanagawa, who informed him that the Japanese troops had almost completely surrounded 300,000 Chinese troops in the vicinity of Nanking and that preliminary negotiations suggested that the Chinese were ready to surrender.[30] Prince Asaka allegedly issued an order to "kill all captives," thus providing official sanction for the crimes which took place during and after the battle.[31] Some authors record that Prince Asaka signed the order for Japanese soldiers in Nanking to "kill all captives"[32] Others claim that lieutenant colonel Isamu Chō, Asaka's aide-de-camp, sent this order under the Prince's sign manual without the Prince's knowledge or assent.[33] However, even if Chō took the initiative on his own, Prince Asaka, who was nominally the officer in charge, gave no orders to stop the carnage. When General Matsui arrived in the city four days after the massacre had begun, he issued strict orders that resulted in the eventual end of the massacre. While the extent of Prince Asaka's responsibility for the massacre remains a matter of debate, the ultimate sanction for the massacre and the crimes committed during the invasion of China were issued in Emperor Hirohito's ratification of the Japanese army's proposition to remove the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners on August 5, 1937 Siege of the city The Japanese military continued to move forward, breaching the last lines of Chinese resistance, and arriving outside the walled city of Nanking on December 9. Demand for surrender At noon on December 9, the military dropped leaflets into the city, urging the surrender of Nanking within 24 hours, promising annihilation if refused.Meanwhile, members of the Committee contacted Tang and suggested a plan for three-day cease-fire, during which the Chinese troops could withdraw without fighting while the Japanese troops would stay in their present position. General Tang agreed with this proposal if the International Committee could acquire permission of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, who had already fled to Hankow to which he had temporarily shifted the military headquarters two days earlier. John Rabe boarded the U.S. gunboat Panay on December 9 and sent two telegrams, one to Chiang Kai-shek by way of the American ambassador in Hankow, and one to the Japanese military authority in Shanghai. The next day he was informed that Chiang Kai-shek, who had ordered that Nanking be defended "to the last man," had refused to accept the proposal.[citation needed] Assault and capture of Nanking Pursuit and mopping-up operations

Soldiers from the Imperial Japanese Army enter Nanking in January 1938 Japanese troops pursued the retreating Chinese army units, primarily in the Xiakuan area to the north of the city walls and around the Zijin Mountain in the east. Although most sources suggest that the final phase of the battle consisted of a one-sided slaughter of Chinese troops by the Japanese, some Japanese historians maintain that the remaining Chinese military still posed a serious threat to the Japanese. Prince Yasuhiko Asaka told a war correspondent later that he was in a very perilous position when his headquarters was ambushed by Chinese forces that were in the midst of fleeing from Nanking east of the city. On the other side of the city, the 11th Company of the 45th Regiment encountered some 20,000 Chinese soldiers who were making their way from Xiakuan.[13] The Japanese army conducted its mopping-up operation both inside and outside the Nanking Safety Zone. Since the area outside the safety zone had been almost completely evacuated, the mopping-up effort was concentrated in the safety zone. The safety zone, an area of 3.85 square kilometres, was literally packed with the remaining population of Nanking. The Japanese army leadership assigned sections of the safety zone to some units to separate alleged plain-clothed soldiers from the civilians |

No comments:

Post a Comment