|

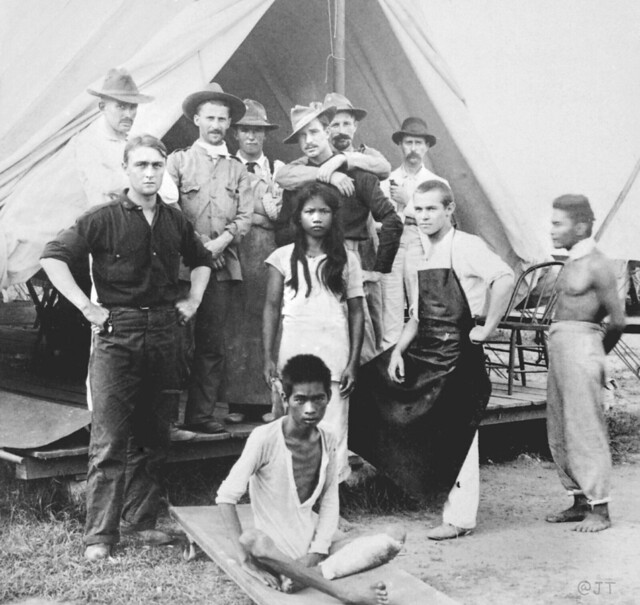

The first Americans encamped in Malabon after the fall and burning of the town, Philippines, c1898 CASUALTIES, February 4, 1899 - July 4, 1902: Filipinos : 20,000 soldiers killed in action; 500,000 civilians died Americans : 4,390 dead (1,053 killed in action; 3,337 other deaths) Photos of the American conquest of the Philippines, an episode also referred to as the Filipino Genocide.

Soundtrack :Campanades a morts, by Lluís Llach.

LETRA (Catalan original)

Campanades a morts

fan un crit per la guerra

dels tres fills que han perdut

les tres campanes negres.

I el poble es recull

quan el lament s'acosta,

ja són tres penes més

que hem de dur a la memòria.

Campanades a morts

per les tres boques closes,

ai d'aquell trobador

que oblidés les tres notes!

Qui ha tallat tot l'alè

d'aquests cossos tan joves,

sense cap més tresor

que la raó dels que ploren?

Assassins de raons, de vides,

que mai no tingueu repòs en cap dels vostres dies

i que en la mort us persegueixin les nostres memòries.

Campanades a morts

fan un crit per la guerra

dels tres fills que han perdut

les tres campanes negres.

II

Obriu-me el ventre

pel seu repòs,

dels meus jardins

porteu les millors flors.

Per aquests homes

caveu-me fons,

i en el meu cos

hi graveu el seu nom.

Que cap oratge

desvetllí el son

d'aquells que han mort

sense tenir el cap cot.

Fotos de la conquista norteamericana de Filipinas, también llamada El Genocidio Filipino.

May 1, 1898: Dewey destroys Spanish fleet at Manila Bay

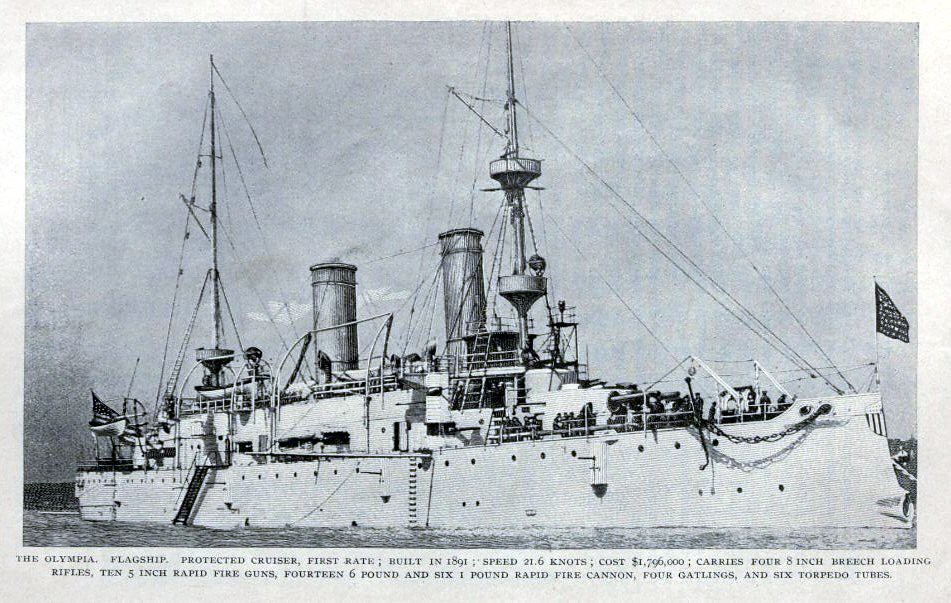

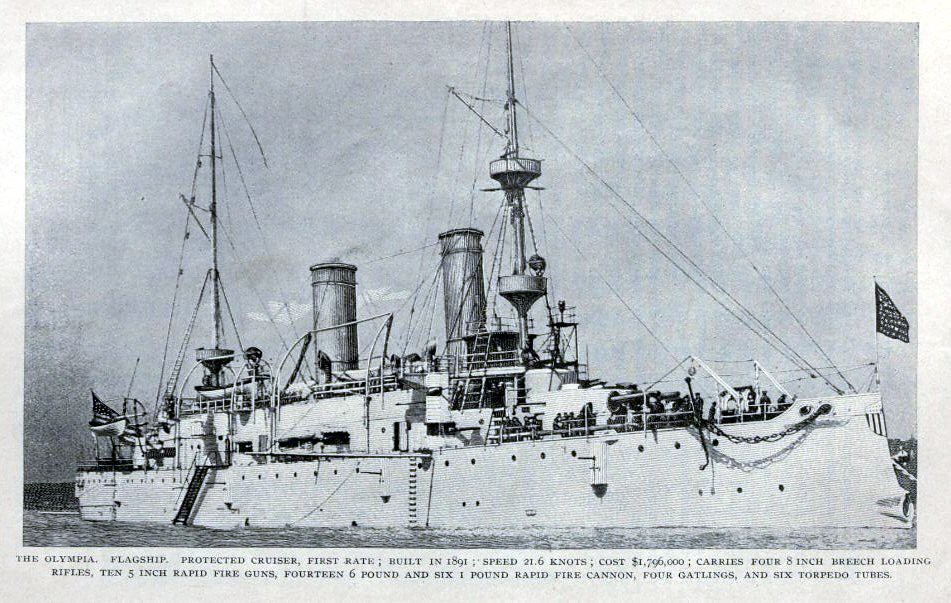

The USS Olympia at Hong Kong Harbor. Commodore George Dewey had his ships' brilliant peacetime white and buff schemes over-painted to war gray; this made them less conspicuous in battle. PHOTO was taken in April 1898.  On April 22, 1898, the US Asiatic Fleet commanded by Commodore George Dewey was riding at anchor in the British port of Hong Kong. Navy On April 22, 1898, the US Asiatic Fleet commanded by Commodore George Dewey was riding at anchor in the British port of Hong Kong. Navy  Secretary John Davis Long (LEFT) cabled the commodore that the United States had begun a blockade of Cuban ports, but that war had not yet been officially announced. Secretary John Davis Long (LEFT) cabled the commodore that the United States had begun a blockade of Cuban ports, but that war had not yet been officially announced.

On April 25, Dewey (RIGHT) was notified that war had begun and received his sailing orders from Secretary Long : "War has commenced between the United States and Spain. Proceed at once to Philippine Islands. Commence operations at once, particularly against the Spanish fleet. You must capture vessels or destroy. Use utmost endeavors."

On that day, due to British neutrality regulations, the American squadron was ordered to leave Hong Kong (ABOVE, in 1898). While Dewey's ships steamed out from the British port, military bands on English vessels played "The Star-Spangled Banner," and their crews cheered the American sailors.

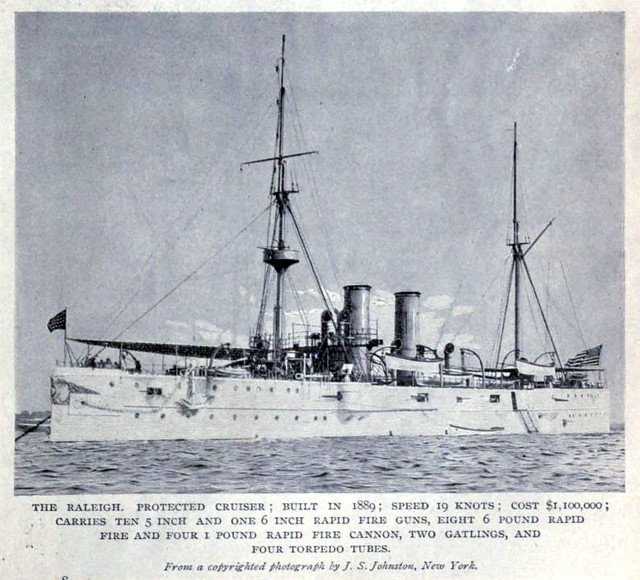

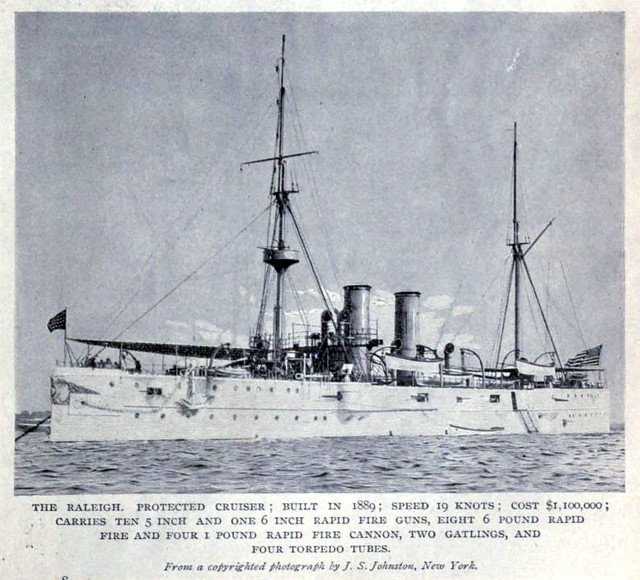

The USS Petrel at Hong Kong, prior to getting swathed in wartime gray, April 15, 1898 Commodore Dewey violated China's neutrality and anchored his fleet about 30 miles (50 km) down the Chinese coast, at Mirs Bay, and waited for further instructions. The squadron consisted of 1,744 officers and men, and 9 vessels: the cruisers Olympia,Baltimore, Raleigh and Boston, the gunboats Concord and Petrel, the revenue cutterMcCulloch, and the transport ships Zafiro and Nanshan.

The USS Concord at Hong Kong wearing wartime gray paint, 1898. The Chinese did not bother to protest, and for two days the crews drilled with torpedoes and quick-fire guns, and aimed their eight-inchers at cliffside targets on Kowloon Peninsula.

The Atlanta Constitution, issue of April 27, 1898. At 2:00 p.m. on April 27, the American squadron raised anchor and left Mirs Bay for the 628-mile run to the Philippines (1,162 km). The Olympia's band blared "El Capitan" and the men shouted, "Remember the Maine!"

The British colony of Hong Kong is located in the upper left corner of this 1899 US army map

Battle of Manila Bay On May 1, the squadron destroyed the antiquated Spanish fleet commanded by Admiral Patricio Montojo in Manila Bay; sunk were 8 vessels: the cruisers Reina Cristina andCastilla, gunboats Don Antonio de Ulloa, Don Juan de Austria, Isla de Luzon, Isla de Cuba, Velasco, and Argos.

Chart (LEFT) shows Dewey's battle track during the Battle of Manila Bay, with X's depicting the positions of the Spanish vessels.

Contemporary satellite photo of the Cavite Peninsula. Cavite City is the current name of Cavite Nuevo. The city proper is divided into five districts: Dalahican, Santa Cruz, Caridad, San Antonio and San Roque. The Sangley Point Naval Base is part of the city and occupies the northernmost portion of the peninsula. The historic island of Corregidor and the adjacent islands and detached rocks of Caballo, Carabao, El Fraile and La Monja found at the mouth of Manila Bay are part of the city's territorial jurisdiction.

A Japanese woodblock print of the Battle of Manila Bay. Print courtesy of the MIT Museum. By 1899, the United States was involved in its first war in Asia. Three others were to follow in the course of the next century: against Japan, North Korea and China, and, finally, Viet Nam. But the first Asian war was against the Filipinos. At the end of the Spanish-American War, the U.S. collected Puerto Rico as a colony, set up a protectorate over Cuba, and annexed the Hawaiian Islands. President William McKinley also forced Spain to cede the Philippine Islands. To the American people, McKinley explained that, almost against his will, he had been led to make the decision to annex: "There was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and christianize them as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died." McKinley was either unaware of or simply chose not to inform the people that, except for some Muslim tribesmen in the south, the Filipinos were Roman Catholics, and, therefore, by most accounts, already Christians. In reality, the annexation of the Philippines was the centerpiece of the "large policy" pushed by the imperialist cabal (neocons of today) to enlist the United States in the ranks of the great powers. To encourage the Americans in their new role, Rudyard Kipling, the British imperialist writer, composed a poem urging them to "take up the White Man's Burden." There was a problem, however. When the war with Spain started, Emilio Aguinaldo, the leader of the Philippine independence movement, had been brought to the islands by Commodore Dewey himself. Aguinaldo had raised an army of Filipino troops who had acquitted themselves well against the Spanish forces. But they had fought side by side with the Americans to gain their independence from Spain, not to change imperial masters. With the Spaniards gone, the Filipinos prepared a constitution for their new country — while McKinley prepared to conquer it. Hostilities broke out in February 1899, and an American army of 60,000 men was sent halfway across the globe to subdue a native people. At first Aguinaldo, whose rebel army had been fighting the Spanish for two years, allied with the U.S. in defeating the Spanish, hoping the U.S. would support the independence of the Philippine republic that he had declared in 1898. But it soon became apparent that the U.S. intended to keep the Philippines as a colony and, in early 1899, the conflict erupted into full war between the U.S. army and Aguinaldo's army. Two years later Aguinaldo was captured. He agreed to swear allegiance to the U.S., and the war was effectively over. In July 1902 the U.S. declared an official end to the war. (In 1946 the U.S. granted independence to the Philippines.)

In September 1899, as intense jungle fighting continued in the Filipino-controlled areas, Aguinaldo published two appeals to Americans. One was a pamphlet entitled A True Narrative of the Philippine Revolution addressed "To All Civilized Nations and Especially to the Great North American Republic," in which he accuses the U.S. of manipulating the Filipino leaders into a false hope of independence. The second was this article published in the North American Review, in which he challenges Americans to consider the Philippine struggle as equivalent to the American Revolution—with the same ideals of freedom and republican government that the U.S. was violating in its foreign policy, he argues. He also warns the U.S. that it is "falling into the pit you have dug for yourselves," and that the American public—even its president—is being misled about the true course of the war. A strong piece to pair with the essays in this section by Mark Twain (a member of the short-lived Anti-Imperialist League), and to introduce students to an oft-neglected war in U.S. history.

Commodore George Dewey (second from right) on the bridge of USS Olympia during the battle of Manila Bay. Others present are (left to right): Samuel Ferguson (apprentice signal boy), John A. McDougall (Marine orderly) and Merrick W. Creagh (Chief Yeoman).

The Olympia's men cheering the Baltimore during the battle of Manila Bay

Sunken Spanish flagship Reina Cristina  One hundred sixty-one Spanish sailors died and 210 were wounded, eight Americans were wounded and there was one non-combat related fatality (heart attack). One hundred sixty-one Spanish sailors died and 210 were wounded, eight Americans were wounded and there was one non-combat related fatality (heart attack).

Admiral Montojo (LEFT) escaped to Manila in a small boat. Montojo was summoned to Madrid in order to explain his defeat in Cavite before the Supreme Court-Martial. He leftManila in October and arrived in Madrid on Nov. 11, 1898. By judicial decree of the Spanish Supreme Court-Martial, (March 1899), Montojo was imprisoned. Later, he was absolved by the Court-Martial but was discharged. In an odd change of events, one of those who defended Admiral Montojo was his former adversary at Cavite, Admiral George Dewey. Montojo died in Madrid, Spain, on Sept. 30, 1917 (Dewey died earlier in the same year, on January 16).

The Cavite arsenal and navy yard. PHOTOS were taken in 1898 or 1899.

Fort Guadalupe, Cavite Navy Yard (photo taken in 1900) The victory gave to the US fleet the complete control of Manila Bay and the naval facilities at Cavite and Sangley Point..

When the news of the victory reached the U.S., Americans cheered ecstatically. Dewey became an instant national hero. Stores soon filled with merchandise bearing his image. Few Americans knew what and where the Philippines were, but the press assured them that the islands were a welcome possession. President McKinley told his confidant, H.H. Kohlsaat, Editor of the Chicago-Times Herald: "When we received the cable from Admiral Dewey telling of the taking of the Philippines I looked up their location on the globe. I could not have told where those darned islands were within 2,000 miles!" [Some months later he said: "If old Dewey had just sailed away when he smashed that Spanish fleet, what a lot of trouble he would have saved us."] On the morning of May 2nd, Dewey notified the Spanish Governor-General that since the underwater Manila-Hong Kong telegraph cable was Manila's only link to the outside world, it should be considered neutral so that he could use it as well. When the Governor-General refused, Dewey dredged up and cut the cable, ending the direct flow of information out of the Philippines. The cable was operated by the British-owned Eastern Extension Australasia China Telegraph Company. [On May 23, Dewey also cut the company's Manila-Capiz cable, severing the electronic connection between Manila and the central Philippine islands of Panay, Cebu, and Negros]. In January of 1899, while fighting between American and Filipino troops was already occurring, President William McKinley issued the “Benevolent Assimilation Proclamation” which announced America’s intent to annex the Philippines and “assimilate” it into the United States. Imagine hearing that one on CNN every day for a month. Sounds like “Healthy Forests” and “Clear Skies,” doesn’t it? You’re right. When the news of the proclamation reached the Philippines it was greeted with all the warmth of a striking cobra. How could Spain cede the Philippines to America when Spain herself no longer ruled it? And what’s all this about “assimilation?” That doesn’t sound very benevolent. There is one answer to all three questions: superior military power, and the United States was not only prepared to use it, but gave the commander of American troops in the Philippines a mandate to “extend by force American sovereignty over this country.” The Treaty of Paris was finally ratified in February of 1899. Angulinda’s Filipino government issued a counter proclamation to McKinley’s “benevolent assimilation,” declaring that they would not allow the United States to occupy the Philippines. So we massacred them. Don’t take my word for it. Listen to one of our own soldiers. Captain Elliott of Kansas described what “benevolent assimilation” really meant: Talk about war being “hell,” this war beats the hottest estimate ever made of that locality. Caloocan was supposed to contain seventeen thousand inhabitants. The Twentieth Kansas swept through it, and now Caloocan contains not one living native. Of the buildings, the battered walls of the great church and dismal prison alone remain. The village of Maypaja, where our first fight occurred on the night of the fourth, had five thousand people on that day—now not one stone remains upon top of another. You can only faintly imagine this terrible scene of desolation. War is worse than hell. And perhaps he is saying to himself, “It is yet another civilized power with its banner of the Prince of Peace in one hand and its loot basket and its butcher knife in the other. Is there no salvation for us but to adopt civilization and lift ourselves down to its level?” American military strength was vastly greater than the Filipinos – in numbers, in equipment, and in training. Yet, just like the British and the Boers, they could not quickly subdue what many American historians arrogantly call the “Filipino Insurrection.” American forces indiscriminately killed natives (women and children included), burned villages, looted homes, and engaged in systematic torture of Filipino captives. The war finally “ended” in 1902 when Aguinaldo was captured through trickery and deceit by General Frederick Funston (right). Several years later, Twain would lay his sight on Funston himself in “A Defense of General Funston,” after Funston labeled all those who had doubts about the war “traitors.” After Angulinda was captured, Filipino guerillas continued to fight American forces until 1913. Many people supported the colonization of the Philippines, and had no troubles with the slaughter of the Filipino “niggers.” No person supported in more than Alfred Beveridge, United States Senator from Indiana: "The Philippines are ours forever. We will not repudiate our duty in the archipelago. We will not abandon our duty in the Orient. We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustee under God, of the civilization of the world." Others like Twain, and Sumner before him, saw a great injustice and refused to be silent. In 1903, George Hoar, distinguished Senator from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, had this to say on the Senate floor to his colleagues who supported the war in the Philippines: “What has been the practical statesmanship which comes from your ideals and sentimentalities? You have wasted six hundred millions of treasure. You have sacrificed nearly ten thousand American lives, the flower of our youth. You have devastated provinces. You have slain uncounted thousands of the people you desire to benefit.”

May 3, 1898: 1Lt. Dion Williams, US Marine Corps, and the marine detachment which ran up the first American flag to fly over the Philippines, render military courtesies to Commodore George Dewey on his first visit ashore.

Four American soldiers at a captured Spanish outpost in Cavite Province. Photo was taken in 1898.  The Spanish Governor-General and military commander, General Basilio de Agustin y Davila (LEFT), through the British consul, Edward H. Rawson-Walker, intimated to Dewey his willingness to surrender to the American squadron. The Spanish Governor-General and military commander, General Basilio de Agustin y Davila (LEFT), through the British consul, Edward H. Rawson-Walker, intimated to Dewey his willingness to surrender to the American squadron.

But Dewey could not entertain the proposition because he had no force with which to occupy Manila. He said, "...I would not for a moment consider the possibility of turning it over to the undisciplined insurgents, who, I feared, might wreak their vengeance upon the Spaniards and indulge in a carnival of loot."

Spanish Captain-General Basilio de Agustin y Davila clothed in the functions of a viceroy surrounded by his staff with a group of the principal officers under his command inManila. The Spanish army garrisoned in Manila consisted of about 13,332 soldiers (8,382 Spanish, 4,950 Filipino).

Gun practice on the Baltimore during the blockade of Manila Bay With no ground troops to attack the city, Dewey blockaded the harbor. He also soon became aware of the dual risks of a Spanish relief expedition and intervention by another power. He cabled Washington and asked for reinforcements.

1st California Volunteer Infantry Regiment heading to the Presidio, May 7, 1898. The US Army started to marshall a force at the Presidio, San Francisco, California, that became the 8th Army Corps, dubbed the Philippine Expeditionary Force, under Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt.

Rear Admiral George Dewey with staff and ship's officers, on board USS Olympia, 1898. On May 11, 1898, Dewey was promoted to Rear Admiral. The few major warships left in the eastern Pacific were also ordered to reinforce Dewey. The cruiser Charleston accompanied the first Army expedition, bringing with her a much-needed ammunition resupply. To provide the Asiatic Squadron with heavy firepower, the monitors Montereyand Monadnock left California in June. These slow ships were nearly two months in passage. Monterey was ready in time to help with Manila's capture, while Monadnock arrived a few days after the Spanish surrender. May 19, 1898: Emilio Aguinaldo Returns

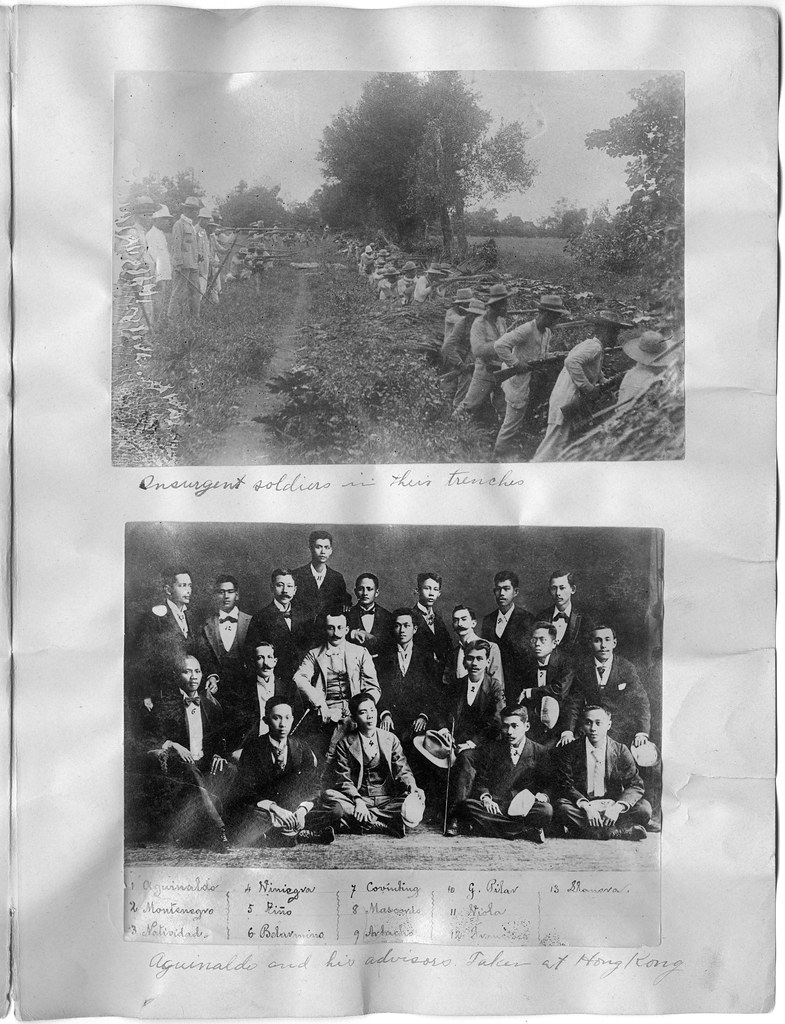

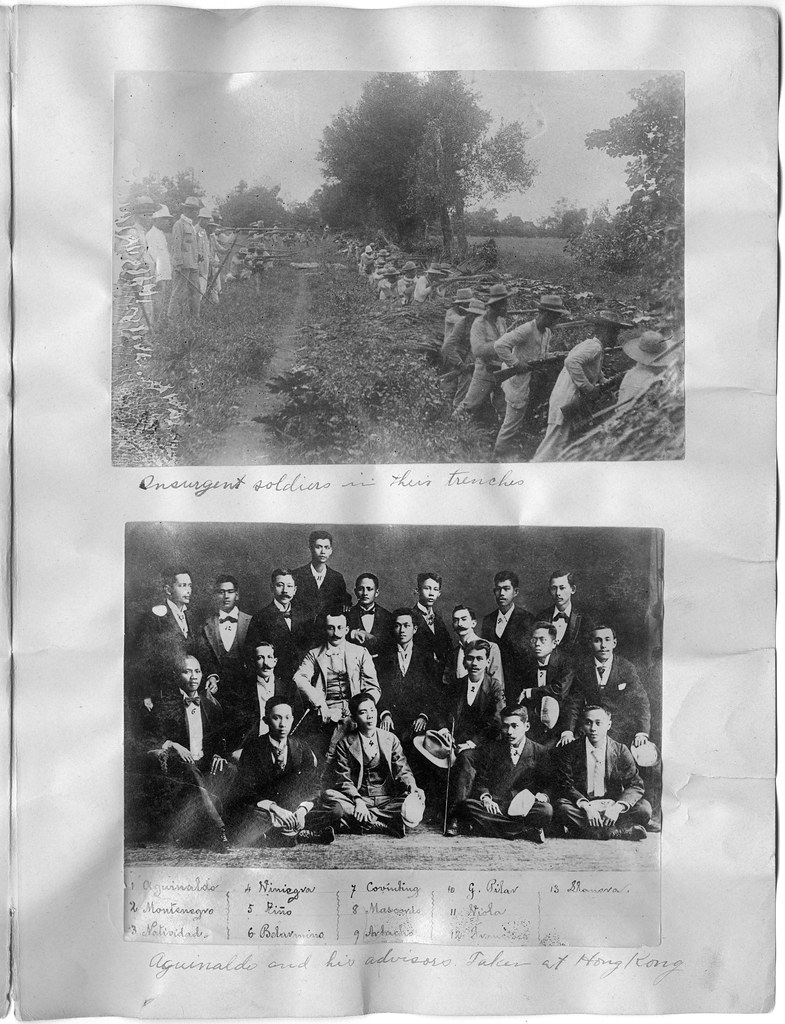

Filipino exiles in Hong Kong, photo taken in early 1898: Emilio Aguinaldo (sitting, 2nd from right) led 36 other revolutionary leaders into exile in the British colony. They were: Pedro Aguinaldo, Tomas Aguinaldo, Joaquin Alejandrino, Celestino Aragon, Jose Aragon, Primitivo Artacho, Vito Belarmino, Agapito Bonzon, Antonio Carlos, Eugenio de la Cruz, Agustin de la Rosa, Gregorio H. del Pilar, Valentin Diaz, Salvador Estrella, Vitaliano Famular, Dr. Anastacio Francisco, Pedro Francisco, Francisco Frani, Maximo Kabigting, Vicente Kagton, Silvestre Legazpi, Teodoro Legazpi, Mariano Llanera, Doroteo Lopez, Vicente Lukban, Lazaro Makapagal, Miguel Malvar, Tomas Mascardo, Antonio Montenegro, Benito Natividad, Carlos Ronquillo, Manuel Tinio, Miguel Valenzuela, Wenceslao Viniegra, Escolastico Viola and Lino Viola. In the run up to the Spanish-American War, several American Consuls - in Hong Kong,Singapore and Manila - sought Emilio Aguinaldo's support. None of them spoke Tagalog, Aguinaldo's own language, and Aguinaldo himself spoke poor Spanish. A British businessman who spoke Tagalog, Howard W. Bray, agreed to act as interpreter. Aguinaldo and Bray maintained later that the Philippines had been promised independence in return for helping the U.S. defeat the Spanish.

Some of the Filipino exiles and Spanish officers in charge of their deportation to Hong Kong. Emilio Aguinaldo is the central figure in the second row; to his right is Lt. Col. Miguel Primo de Rivera, nephew of the Spanish Governor-General. PHOTO was taken in Hong Kong in early 1898.

Hong Kong: Some of the exiles at a park with British acquaintances. Photo taken in 1898. In Hong Kong, Aguinaldo was told by U.S. consul Rounsenville Wildman that Dewey wanted him to return to the Philippines to resume the Filipino resistance.

The San Francisco Call, May 18, 1898 Arriving in Manila with thirteen of his staff on May 19 aboard the American revenue cutter McCulloch, Aguinaldo reassumed command of Filipino rebel forces. Although he and Dewey spoke, no one knows the substance of the discussions– Dewey only spoke Spanish, Aguinaldo spoke it poorly and there was no intermediary. of Filipino rebel forces. Although he and Dewey spoke, no one knows the substance of the discussions– Dewey only spoke Spanish, Aguinaldo spoke it poorly and there was no intermediary. [Years later, Aguinaldo recalled a meeting with Dewey: "I asked whether it was true that he had sent all the telegrams to the Consul at Singapore, Mr. Pratt, which that gentleman had told me he received in regard to myself. The Admiral replied in the affirmative, adding that the United States had come to the Philippines to protect the natives and free them from the yoke of Spain. He said, moreover, that America is exceedingly well off as regards territory, revenue, and resources and therefore needs no colonies, assuring me finally that there was no occasion for me to entertain any doubts whatever about the recognition of the Independence of the Philippines by the United States."] [Aguinaldo, in his book, "A Second Look At America," admitted he naively believed that Dewey "acted in good faith" on behalf of the Filipinos.]

Cavite Province: A medic attends to a wounded Filipino soldier. Photo taken in May or June 1898.

Cavite Province: The same wounded Filipino soldier shown in preceding photo is loaded onto a cart. Photo taken in May or June 1898. Five days after his arrival, on May 24, Aguinaldo temporarily established a dictatorial government, but plans were afoot to proclaim  the independence of the country. A democratic government would then be set up. the independence of the country. A democratic government would then be set up. In late May, Dewey was ordered by the U.S. Department of the Navy to distance himself from Aguinaldo lest he make untoward commitments to the Philippine forces. The official directive was not necessary; Dewey had already made up his mind beforehand: "From my observation of Aguinaldo and his advisers I decided that it would be unwise to co-operate with him or his adherents in an official manner... In short, my policy was to avoid any entangling alliance with the insurgents, while I appreciated that, pending the arrival of our troops, they might be of service." [RIGHT, Aguinaldo's headquarters inside the Cavite navy yard, May 1898]. Dewey referred to the Filipinos as "the Indians" and promised Washington, D.C. that he would "enter the city [Manila] and keep the Indians out."

Issue of May 31, 1898

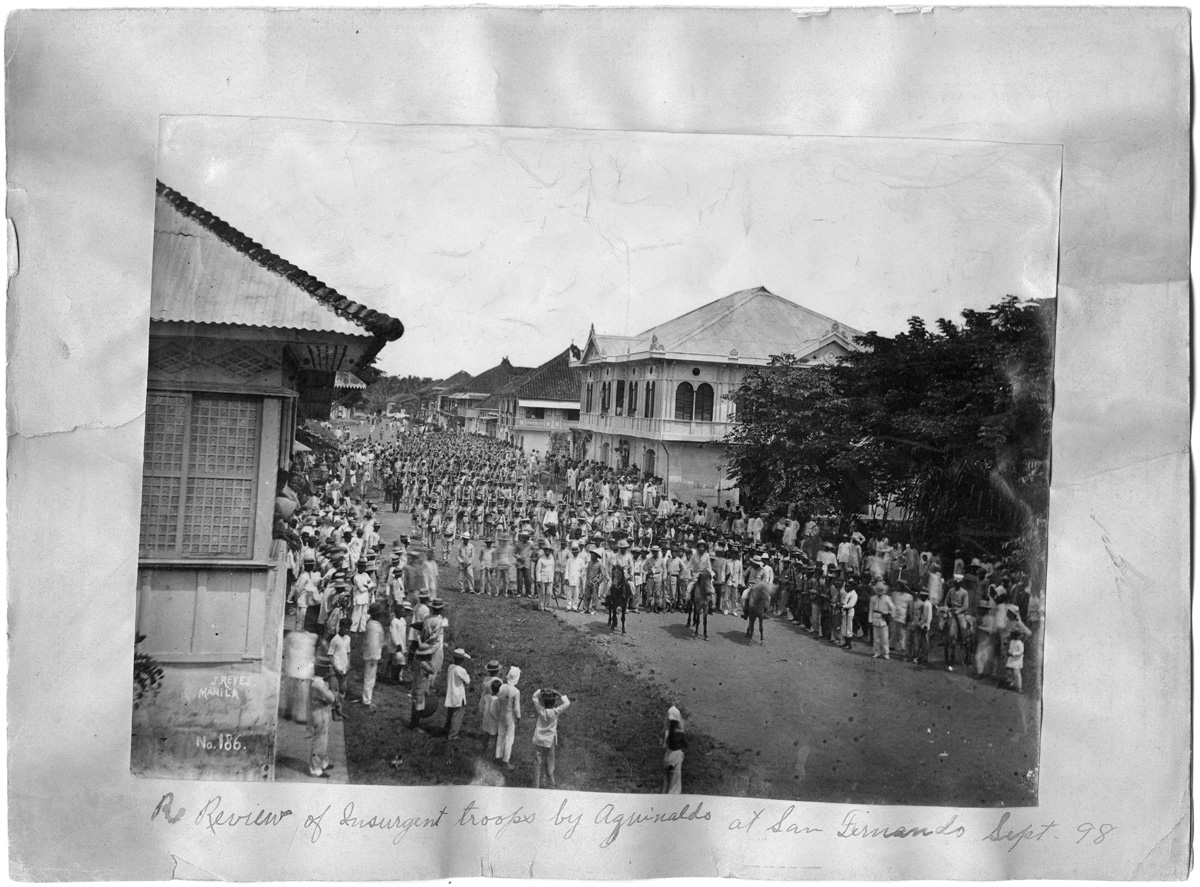

Issue of June 7, 1898 By early June, with no arms supplied by Dewey, Aguinaldo's forces had overwhelmed Spanish garrisons in Cavite and around Manila, surrounded the capital with 14 miles of trenches, captured the Manila waterworks and shut off access or escape by the Pasig River. Links were established with other movements throughout the country. With the exception of Muslim areas on Mindanao and nearby islands, the Filipinos had taken effective control of the rest of the Philippines. Aguinaldo's 12,000 troops kept the Spanish soldiers bottled up inside Manila until American troop reinforcements could arrive.

Philippine army soldiers are seen here guarding 3 Filipino judicial prisoners in the stocks. PHOTO was taken in 1898. Aguinaldo was concerned, however, that the Americans would not commit to paper a statement of support for Philippine independence. [John Foreman, American historian of the early Philippine-American War period stated that, "Aguinaldo and his inexperienced followers were so completely carried away by the humanitarian avowels of the greatest republic the world had seen that they willingly consented to cooperate with the Americans on mere verbal promises, instead of a written agreement which could be held binding on the U.S. Government."]

Spanish mestizas. LEFT photo was taken at Manila's Teatro Zorillain January 1894; RIGHT photo was taken in Cavite in 1898.

Photo taken in 1898 in Manila

Upper-class native Filipino women. Photos taken in the late 1890's.

Native Filipino women. Photo taken in the late 1890's.

Assembly room (LEFT) and library (RIGHT) of the private Universidad de Santo Tomas, at Intramuros district, Manila, in 1887. It was founded on April 28, 1611 by Dominican friars and until 1927 did not accept women (The same year that it moved to Sampaloc district). During the Spanish era, only affluent native Filipinos could afford to send their sons to the school. Now known as the University of Santo Tomas (UST), it has the oldest extant university charter in the Philippines. The UST produced four Philippine presidents and many revolutionary heroes, including Jose Rizal, the national hero.

The Colegio de San Juan de Letran in Intramuros district, Manila, and students, in 1887. The private Roman Catholic institution, founded in 1620, was and still is, owned by priests of the Dominican Order. It catered to the sons of wealthy native Filipinos and did not accept women until the 1970's. It produced four Philippine presidents and many revolutionary heroes; it is the only Philippine school that has graduated a Catholic Saint that actually lived and studied inside its original campus (Vietnamese Saint Vicente Liem de la Paz). Letran is the only Spanish-era school that still stands on its original site in Intramuros.

Scenes at the secondary school Ateneo Municipal de Manila, Intramuros district, Manila, in 1887. Now known as the Ateneo de Manila University, a private coed institution run by the Jesuits, it began on Oct. 1, 1859 when the latter took over the Escuela Municipal, then a small private primary school maintained for the children of Spanish residents. In 1865, it became the Ateneo Municipal de Manila when it converted to a secondary school for boys, and began admitting native Filipinos who invariably came from well-to-do families. The Ateneo attained college status in 1908. It moved to Ermita district, Manila, in 1932. The campus was devastated in 1945 during World War II. In 1952, most of the Ateneo units relocated to Loyola Heights, Quezon City. It became a university in 1959. It admitted women for the first time in 1973. The Ateneo produced many revolutionary heroes, including the national hero, Jose Rizal.

Manila: Native Filipino schoolboys of the public Escuela Municipal de Instrucción Primaria de Quiapo. Photo taken in 1887.

Montalban, Morong Province: A little village school for girls under a bigmango tree. Photo, taken in mid-May 1894, includes 3 American businessmen.

Chinese merchants in Manila. Photos taken in the late 1890's

Chinese merchants: a chocolate-maker (LEFT) and a textile fabric manufacturer (RIGHT). Photos taken at Manila in the late 1890's.

Filipino fighters and some American soldiers. Photo taken in 1898.

June 3, 1898: Spanish battery of two 8-centimeter caliber guns firing at Filipinos at the Zapote River bridge, Cavite Province. The Spaniards kept up a continuous fire with their field guns and Mauser rifles before charging the bridge.

June 3, 1898: Spanish soldiers on Zapote Bridge. It was a temporary occupation; the Filipinos, numbering about 500, counterattacked and sent the Spanish force of 3,500 reeling back.

Filipinos moving captured Spanish cannon

Filipinos with captured Spanish field-piece

Filipino soldiers with their artillery in front of Fort San Felipe Neri, Cavite Province. Photo taken in 1898.

Filipino soldiers assemble in front of the San Nicolas de Tolentino Church in Parañaque, a few miles south of Manila. The Filipino army converted the church and convent into a storehouse and magazine. PHOTO was taken in 1898.

Spanish troops in Cebu Island

The USS Olympia While awaiting the arrival of ground troops, Dewey welcomed aboard his flagship USS Olympia members of the media who clamored for interviews. Numerous vessels of other foreign nations, most conspicuously those of Britain, Germany, France, and Japan, arrived almost daily in Manila Bay. These came under the pretext of guarding the safety of their own citizens in Manila, but their crews kept a watchful eye on the methods and activities of the American Naval commander. The German fleet of five ships, commanded by Vice Admiral Otto von Diederichs (RIGHT, in 1898) and ostensibly in Philippine waters to protect German interests (a single import firm), acted provocatively—cutting in front of US ships, refusing to salute the US flag (according to customs of naval courtesy), taking soundings of the harbor, and landing supplies for the besieged Spanish. Germany was eager to take advantage of whatever opportunities the conflict in the Philippines might afford. Dewey called the bluff of the German vice admiral, threatening a fight if his aggressive activities continued, and the Germans backed down. In recognition of George Dewey's leadership during the Battle of Manila Bay, a special medal known as the Dewey Medal was presented to the officers and sailors under Commodore Dewey's command. Dewey was later honored with promotion to the special rank of Admiral of the Navy; a rank that no one has held before or since in the US Navy. Years later in U.S. Senate hearings, Admiral Dewey testified, "I never treated him (Aguinaldo) as an ally, except to assist me in my operations against the Spaniards." Dewey was born on Dec. 26, 1837 in Montpelier, Vermont. He graduated from the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland on June 18, 1858. During the American Civil War he served with Admiral David Farragut during the Battle of New Orleans and as part of the Atlantic blockade. He was commissioned as a Commodore on Feb. 28, 1896. On Nov. 30, 1897 he was named commander of the Asiatic Squadron, thanks to the help of strong political allies, including Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt. He held the rank of Admiral of the Navy until his death in Washington, DC, on Jan. 16, 1917. General Emilio Aguinaldo  Aguinaldo was the first and youngest President of the Philippines. He was born onMarch 22, 1869 in Cavite El Viejo (now Kawit), Cavite province. He was slender and stood at five feet and three inches. He studied at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran. He quit his studies at age 17 when his father died so that he could take care of the family farm and engage in business. Aguinaldo was the first and youngest President of the Philippines. He was born onMarch 22, 1869 in Cavite El Viejo (now Kawit), Cavite province. He was slender and stood at five feet and three inches. He studied at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran. He quit his studies at age 17 when his father died so that he could take care of the family farm and engage in business.

He joined freemasonry and was made a master mason on Jan. 1, 1895 at Pilar Lodge No. 203 (now Pilar Lodge No. 15) at Imus,Cavite and was founder of Magdalo Lodge No. 3. On March 14, 1896, he joined theKatipunan and for his name in the secret revolutionary society, he chose Magdalo, after the patron saint of Cavite El Viejo, Mary Magdalene. He was initiated in the house of Katipunan Supremo Andres Bonifacio on Cervantes St. (now Rizal Ave.), Manila. Aguinaldo married his first wife, Hilaria del Rosario of Imus, Cavite in 1896. From that marriage five children (Miguel, Carmen, Emilio, Jr., Maria and Cristina) were born. When the revolution against Spain broke out on Aug. 30, 1896, he was the capitan municipal (mayor) of Cavite el Viejo. Aguinaldo defeated the best of the Spanish generals: Ernesto de Aguirre in the Battle of Imus, Sept. 3, 1896; Ramon Blanco in the Battle of Binakayan, Nov. 9-11, 1896; and Antonio Zaballa in the Battle of Anabu, February 1897). He assumed total control of the Filipino revolutionary forces after executing Andres Bonifacio on May 10, 1897. He was captured by the Americans led by Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston on March 23, 1901 in remote Palanan, Isabela Province. On April 1, 1901, he pledged allegiance to the United States. (His son, Emilio Jr., graduated from West Point in 1927, in the same class as Gen. Funston's son.) On March 6, 1921, his first wife, Hilaria, died. On July 14, 1930, at age 61, Aguinaldo married Maria Agoncillo, 49-year-old niece of Felipe Agoncillo, the pioneer Filipino diplomat. On Feb. 6, 1964, less than a year after the death of his second wife, Aguinaldo died of coronary thrombosis, at the age of 95, at the Veterans Memorial Hospital in Quezon City. His remains are buried at the Aguinaldo Shrine in Kawit, Cavite Province. US Infantry, Naval Reinforcements, Embark For Manila, May 25 - June 29, 1898

The US Army forces that invaded the Philippines in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars assembled at the Presidio (ABOVE, in 1898) on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula, California.

Camps of the 51st Iowa and 1st New York Volunteers at the Presidio, 1898. The Iowans went but the New Yorkers did not proceed to the Philippines. The Presidio was originally a Spanish Fort built by Jose Joaquin Moraga in 1776. It was seized by the U.S. Military in 1846, officially opened in 1848, and became home to several Army headquarters and units. During its long history, the Presidio was involved in most of America's military engagements in the Pacific. It was the center for defense of the Western U.S. during World War II. The infamous order to inter Japanese-Americans, including citizens, during World War II was signed at the Presidio. Until its closure in 1995, the Presidio was the longest continuously operated military base in the United States.

Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., at the Presidio, 1898 The lack of transport accommodation, which was corrected by sending vessels from the Atlantic coast of the United States, coupled with the imperative necessity for dispatching troops immediately to the Philippines, resulted in the movement of the 8th Army Corps by 7 installments, extending over a period from May to October. Only 3 of these expeditions [470 officers and 10,464 men] reached Manila in time to take part in the assault and capture of that city on August 13. They were: First Expedition, 115 officers and 2,386 men,commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Anderson: 1st California Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 2nd Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 14th United States Infantry Regiment (5 companies); California Volunteer Artillery (detachment). Steamships: City of Sidney, Australia, and City of Peking [RIGHT, Harper's Weekly, June 11, 1898 issue]. Sailed May 25, arrived Manila June 30. Second Expedition, 158 officers and 3,428 men, commanded by Brig. Gen. Felix V. Greene: 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 1st Nebraska Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 10th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 18th United States Infantry Regiment (4 companies); 23rd United States Infantry Regiment (4 companies); Utah Volunteer Artillery (2 batteries); United States Engineers (detachment). Steamships: China, Colon, and Zealandia. Sailed June 15, arrived Manila July 17.

Men of Company D, 1st Idaho Volunteers, who sailed with the Third Expedition to the Philippines in June 1898. Photo was taken in May 1898. Third Expedition, 197 officers, 4,650 men, commanded by Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt accompanying: 18th United States Infantry Regiment (4 companies); 23rd United States Infantry Regiment (4 companies); 3rd United States Artillery acting as Infantry (4 batteries); United States Engineers Battalion (1 company); 1st Idaho Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 13th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 1st North Dakota Volunteer Infantry Regiment; Astor Volunteer Artillery; Hospital and Signal Corps (detachments). Steamships: Senator, Morgan City, City of Para, Indiana, Ohio, Valencia, and Newport. Sailed June 27 and 29, arrived Manila July 25 and 31.

Farewells at Camp Merritt, just outside the Presidio, San Francisco. The camp was established on May 29, 1898 but abandoned on August 27 of the same year due to problems with disease, mostly measles and typhoid. The remaining troops bound for the Philippines were moved to Camps Merriam and Miller a bit north at the Presidio.

Company F, 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry Regiment, at Camp Merritt, 1898

Dinner at the San Francisco armory to 1st California Volunteers, May 1898.

1st Nebraska Volunteers from Nebraska State University, 1898

The Lombard Gate of the Presidio, built in 1896, where most US troops en route to the Philippines passed through to meet awaiting ships.

The troops marched down Lombard Street to Van Ness, then to Market Street to the docks.

The Lombard Gate, the main entrance to the Presidio, as it looks in contemporary times.

Original caption: "Soldiers and their Sweethearts, on the Eve of Departure for Manila." Photo taken in 1898 in San Francisco.

1st California Volunteers boarding the City of Peking, San Francisco Bay, May 25, 1898

City of Peking leaving San Francisco Bay with the 1st California Volunteer Infantry Regiment aboard, First Expedition, May 25, 1898

The First Expedition stopped over at Honolulu, Hawaii, on June 1-4. Photo shows Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Anderson visiting the USS Charleston at Honolulu Bay. The cruiser convoyed the expedition to Manila.

USS Charleston, at Hong Kong Harbor, 1898. The protected cruiser convoyed the First Expedition from Hawaii to Manila, June 4-30, 1898. In 1899, during the Philippine-American War, she bombarded Filipino positions to aid Army forces advancing ashore, and took part in the capture of Subic Bay in September 1899. Charleston grounded and was wrecked beyond salvage near Camiguin Island north of Luzon on Nov. 2, 1899.

The USS Monterey is seen off Mare Island Naval Yard, Vallejo, California, 23 miles (37 km) northeast of San Francisco. The monitor sailed for Manila Bay on June 11 and arrived there on August 13. Photo was taken in June 1898.

1st Nebraska Volunteers embarking for Manila with the Second Expedition, June 15, 1898

The Second Expedition leaves San Francisco for the Philippines, June 15, 1898.

The transport China leaving for Manila as part of the Second Expedition. On board were the 18th US Infantry Regiment (Companies A and G); 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry Regiment; Utah Volunteer Light Artillery (Battery B, Sections 3,4,5); and US Volunteer Engineers (Company A), June 15,1898.

USS Monadnock enroute to Manila from San Francisco Bay, June 23 - Aug. 16, 1898

USS Valencia leaving San Francisco with the Third Expedition aboard, June 27, 1898. The transport carried the 1st North Dakota Volunteer Infantry Regiment; 1st Washington Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Companies F, G, I, and L); and the California Heavy Artillery (Batteries A and D).

The USS Indiana leaving San Francisco for the Philippines, Third Expedition, June 27, 1898. On board were the 18th US Infantry Regiment (Companies D and H); 23rd US Infantry Regiment (Companies B, C, G, and L); US Engineers Battalion (Company A); and 1st North Dakota Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Company H). Aug. 13, 1898: Mock Battle of Manila

PEACE PROTOCOL, Aug. 12, 1898, 4:23 p.m., Washington, D.C. [August 13, 4:23 a.m. in Manila] : Jules Cambon, Ambassador of France and representing Spain [SEATED, left] and William R. Day, U.S. Secretary of State [SEATED, near center], sign the protocol suspending hostilities and defining the terms on which peace negotiations were to be carried on between the United States and Spain. The protocol was signed in the presence of Pres. William R. Mckinley [STANDING, 4th from right].

The mock battle of Manila was staged on August 13. At 7:30 a.m., with American and Spanish commanders unaware that a peace protocol had been signed between their governments a few hours earlier, the battle for Manila commenced. Admiral Dewey had cut the only cable that linked Manila to the outside world on May 2nd; news of the war's end reached neither General Jaudenes or Admiral Dewey until August 16th.

13th Minnesota Volunteers fighting in the woods near Manila Capt. Thomas Bentley Mott, aide to Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, wrote: "...the bugle sounded the advance, the whole camp sent up a tremendous cheer, showing that neither rain, the darkness of the night, nor the unseen foe could dampen the involuntary delight of the men at the idea of at last getting at their enemy."

A carabao (water buffalo) drags a gun of the Utah Light Battery into position General MacArthur's 1st Brigade began its movement towards the Spanish positions on the road leading to Pasay. The terrain was swampy, the roads muddy, but by 8:05a.m. most of the elements had reached their forward positions and taken shelter for the opening volley.

1st Nebraska Volunteers moving on the seashore toward Manila

1st Colorado Volunteers kneeling on the beach to fire Less than a mile to the west, General Greene's 2nd Brigade was making its advance along the beach. Leading the way was the 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry Regiment, followed by volunteer regiments from California, Nebraska, Utah, Pennsylvania, andOregon. Ahead lay the Spanish fortification at Malate district, Fort San Antonio de Abad.

Company I of the 1st Colorado Volunteers advances through the grass

Fort San Antonio de Abad: Photo shows damage from Admiral Dewey's naval guns At 9:45 a.m., two of Admiral George Dewey's ships (the cruiser Olympia and the gunboat Petrel) began bombarding Fort San Antonio de Abad. There was only sporadic and light return fire. As the 1st Colorado Volunteers neared its walls, the naval bombardment stopped.

Aug. 13, 1898: Two wounded Spanish soldiers found by the Americans inside Fort San Antonio de Abad. The fort was deserted, save for two dead and two wounded Spaniards.

Original caption: "From the staff at left, the First Colorado lowered the Spanish and swung out the American flag." Fort San Antonio de Abad, Malate district, Manila

1st Colorado Volunteers occupy Fort San Antonio de Abad in Malate district, Manila At 10:35 a.m. Capt. Alexander M. Brooks of Denver, Colorado raised the Stars and Stripes over the captured fort.

Original caption: "Bamboo intrenchment of the Filipinos across the Manila and Dagupan railway. The cannon is a bronze piece captured from the Spaniards, June 1898". As the naval bombardment ended and the American forces continued north in two columns, the Filipinos --- who had not been apprised of the script ---raced to join the battle. They thought there was a real battle going on that would liberate their capitol and they did not want to be left out. The Filipinos assaulted from four directions - the column of General Pio del Pilar took Sampaloc district; that of General Gregorio del Pilar took Tondo district, that of General Mariano Noriel took Singalong and Paco districts; that of General Artemio Ricarte routed the Spaniards in Sta. Ana district and pursued them all the way to Intramuros. General Greene's 2nd Brigade left Malate and continued along the beach.

Aug. 13, 1898: 1st Colorado Volunteers entering Ermita district, Manila, close to Intramuros.

Aug. 13, 1898: The first 2 American soldiers killed during the battle of Manila.

Blockhouse No. 14. Around this spot a great deal of the fighting of August 13 took place. A shell from a Utah gun took away the corner.

The gun that destroyed Spanish Blockhouse #14 Meanwhile, in the east, MacArthur's 1st Brigade moved through the Spanish trenches, overran Blockhouse #14, and confronted the Spanish position at Blockhouse #20 near Singalong.

Photo taken in 1898 or 1899: 13th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment Gatling Gun crew in the Philippines; the Minnesotans arrived in Manila on Aug. 7, 1898 and left on Aug. 10, 1899. The Regiment was mustered out with: 51 officers and 952 men; 6 officers and 68 men were wounded in action, 2 officers and 42 men died (4 Killed in Action, 1 officer and 2 men died of wounds,1 officer and 33 men died of disease, 1 drowned). When the 1st Brigade's 13th Minnesota Volunteers approached, the Spanish defenders fired a few rounds in a token resistance. It was met by a similarly light return fire from the Americans. Hearing the sound of the skirmish, the Filipinos rushed into the foray. A pitched battle ensued, the soldiers of the 13th Minnesota caught in a cross-fire between the Spaniards ahead of them and the Filipino forces behind them.

Astor Battery crew going to the front The men of the Astor Battery charged the stronghold in a pistol attack which saw the Spanish withdraw. It was probably at Blockhouse #20 that the Americans prohibited the Filipinos from proceeding any farther, and MacArthur's advance the rest of the way to the central city was unopposed.

US Third Artillery acting as infantry. In backqround is the strongest Spanish blockhouse outside the walled district of Intramuros, Manila. At 11:00 a.m., as the two American columns converged on Intramuros, Admiral Dewey hoisted the international signal flag "Do you surrender?".

Meanwhile, General Greene and his troops had reached the Luneta, the city promenade (ABOVE, pre-war 1890's), where they were confronted with a heavily defended blockhouse, and a group of Spanish soldiers who, like the Filipinos, apparently were not privy to the unfolding script. The periodic sniping from the Filipinos at the outskirts made the Spanish wary of an American double-cross, while  Admiral Dewey wondered if the Spanish were about to pull some kind of quick trick when the surrender flag failed to rise over the city. A huge Spanish flag continued to float over the city walls near one of the heavy batteries. Admiral Dewey wondered if the Spanish were about to pull some kind of quick trick when the surrender flag failed to rise over the city. A huge Spanish flag continued to float over the city walls near one of the heavy batteries. At 11:45 a.m., the Belgian consul's launch drew alongside the Olympia. Consul Edouard Andre (LEFT) conferred with Admiral Dewey. Flag Lt. Thomas Brumby took the largest American flag on the ship and went aboard the launch. The launch steamed away toward Manila, 1,500 yards away. At 12:00 p.m., the international signal "C.F.L.", meaning "Hold conference", was hoisted over the city walls.

At 2:33 p.m., Lt. Brumby returned and reported that the Spaniards would surrender as soon as General Merritt got 600 to 700 American troops inside Intramuros to protect them from the Filipinos. Admiral Dewey ordered Lt. Brumby to tell General Merritt that he agreed to anything.

American troops marching into Intramuros The Americans rushed into Intramuros.

At 5:45 p.m., the Spanish flag went down and Lt. Brumby (ABOVE, in 1898) hoisted the huge American flag in its place. The 2nd Oregon band struck up "The Star-Spangled Banner" while the Spanish women wept. The ships of the US fleet saluted the new flag with 21 guns each. In ten minutes 189 saluting charges were fired.

Programme of the musical concert on board Dewey's flagship, August 13th, the day of the fall of Manila At 6:00 p.m., the band on the Olympia struck up "The Victory of Manila".

The squad of 2nd Oregon Volunteers detailed to escort and raise the American flag over Manila.

Aug. 13, 1898: Group of American officers before the Puerta Real ("Royal Gate") of Intramuros, Manila.

Terms of capitulation were promptly agreed upon between American and Spanish commanders and the occupation of the Spanish capital of the Philippines was complete. The Americans at once began to fraternize with their Spanish counterparts.

Squad of Spanish prisoners, surrendered to Brig. Gen. Francis V. Greene on Aug. 13, 1898

After the American flag was raised over Intramuros, Aguinaldo demanded joint occupation. General Merritt immediately cabled Brig. Gen. Henry C. Corbin, US Army Adjutant-General, in Washington, D.C.: "Since occupation of the town and suburbs the insurgents on outside are pressing demand for joint occupation of the city. Situation difficult. Inform me at once how far I shall proceed in forcing obedience in this matter and others that may arise. Is Government willing to use all means to make the natives submit to the authority of the United States?"

An American soldier and two native Filipino policemen guard an entrance to Intramuros, Manila. PHOTO was taken in late 1898. Meanwhile, by 10:00 p.m., 10,000 American troops were in Intramuros; the 2nd Oregon Volunteers guarded its 9 entrances. General Greene marched his 2nd Brigade around Intramuros into Binondo district.

Audience room in the Malacañan Palace at San Miguel district, Manila. The 1st California Volunteers were sent east to the fashionable district of San Miguel and took over Malacañan Palace, official residence of the Spanish governor-general.

1st Colorado Volunteers marching in Manila The 1st Colorado Volunteers were sent into Tondo district and the 1st Nebraska Volunteers were established on the north shore of the Pasig river. General MacArthur's 1st Brigade patrolled Ermita and Malate districts.

1st Nebraska Volunteers in formation near their quarters at Binondo, Manila, 1898.

Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt and Brig. Gen. Francis Greene inspecting Fort San Antonio de Abad after the battle.

On Aug. 17, 1898, General Merritt received the following reply from General Corbin: "The President directs that there must be no joint occupation with the insurgents. The United States in the possession of Manila City, Manila Bay, and harbor must preserve the peace and protect persons and property within the territory occupied by their military and naval forces. The insurgents and all others must recognize the military occupation and authority of the United States and the cessation of hostilities proclaimed by the President. Use whatever means in your judgment are necessary to this end. All law-abiding people must be treated alike." The Americans then told Aguinaldo bluntly that his army would be fired upon if it crossed into Intramuros.

The Filipinos were infuriated at being denied triumphant entry into their own capital. The hot-headed Filipino generals thought it was time to strike at the Americans, but Aguinaldo stayed calm and refused to be pushed into a new war. However, relations continued to deteriorate.

A US soldier is photographed beside a stack of cannonballs near the Santa Lucia gate of Intramuros district, Manila.

A modern Spanish Krupp gun, 1898.

Spanish POWs held by the Americans in Manila

Spanish POWs held by the Americans in Manila

Spanish POWs held by the Americans in Manila

Spanish POWs quartered in Intramuros, Manila, receiving their rations.

Spanish POWs quartered in Intramuros, Manila, receiving their rations.

Spanish soldiers in the southern Philippines awaiting repatriation to Spain; about 3,000 were shipped out

Spanish arms captured by the Americans (20,000 Mausers, 3,000 Remingtons, 18 modern cannon and many of the obsolete pattern)

Original caption: "American troops guarding the bridge over the river Pasig on the afternoon of the surrender."

US troops on the Escolta, Manila; not too far from here, on Calle Lacoste in nearby Santa Cruz district, an American guard shot and killed a seven-year-old Filipino boy for taking a banana from a Chinese fruit vendor.

Two American soldiers pose with their .45-70 Springfield Trapdoor rifles. Photo was taken at the Centro Artistico Fotografico ("Photographic Arts Center") in Manila in late 1898.

Graves of American soldiers killed in Manila. The "mock" Battle of Manila was not entirely bloodless. Spanish soldiers who were not privy to the "script" put up serious resistance at a blockhouse close to the city and in a few other areas. Six Americans died while the Spanish suffered 49 killed and 100 wounded. Overall, 17 Americans were killed fighting the Spaniards, 11 on July 31, August 1-2 and August 5 in skirmishes at Malate district.

4th US Regular Infantry Regiment encampment at the Luneta, Manila

V. Tokizama, Japanese military attache to the Philippines with Colonel Harry Clay Kessler (CO, 1st Montana Volunteers), Major Robert H. Fitzhugh and 1Lt. William B. Knowlton; photo taken in Manila, 1898

A squad of American soldiers is enthralled by the Filipino "national sport" of cockfighting

The Ayuntamiento in Intramuros district, Manila. Photo taken in 1899.

Americans in Manila. Photo taken in 1898. The arrogance of the Americans and their continuing presence unsettled the Filipinos.

The 1st South Dakota Volunteer Infantry Regiment at rest at the Presidio, San Francisco. The regiment, consisting of 46 officers and 983 enlisted men, was commanded by Col. Alfred S. Frost. It left the Presidio on July 23, 1898 and arrived at Cavite Province, in Manila Bay, on Aug. 31, 1898.

The 38th US Volunteer Infantry Regiment upon their arrival at Manila, Dec. 26, 1899. Questions on their actual motives surfaced with the continuous arrival of American reinforcements, when there was no Spanish enemy left to fight.

13th Minnesota Volunteers, acting as police, raid an opium den and arrest 4 Chinese addicts. Photo was taken in Manila in late 1898. It did not take long for the Filipinos to realize the genuine intentions of the United States: the Americans were in the islands to stay.

Soon after the Spanish surrender at Manila, Pvt. Fred Hinchman, US Army Corps of Engineers, wrote his family about the Filipino soldiers: "We shall now have to disarm and scatter these abominable, semi-human monkeys." [John Durand, The Boys: 1st North Dakota Volunteers in the Philippines, Puzzlebox Press, 2010, p. 132]. Aug. 24, 1898: First Filipino-American Fatal Encounter

Calle del Arsenal, the main street in Cavite Nuevo, Cavite Province. Photo was taken in 1897. On Wednesday, Aug. 24, 1898, the first fatal encounter between the Filipinos and Americans took place in Cavite Nuevo (now Cavite City), Cavite Province. The U.S. Army put it down as a street fight. Pvt. George H. Hudson of Battery B, Utah Light Artillery Regiment, was killed; Cpl. William Q. Anderson of the same unit, and four troopers of the 4th U.S. Cavalry Regiment were wounded. On Saturday, Aug. 27, 1898, the New York Times reported:

Internal Filipino communications reported that the Utah artillerymen were drunk at the time.

American soldiers and Filipino civilians at Cavite Nuevo. Photo was taken in 1898-1899.

American soldiers and Filipino children at Cavite Nuevo, 1898-1899. Aug. 29, 1898: General Otis Becomes New Commander of 8th US Army Corps, Orders Philippine Army To Leave Manila

Major Generals Wesley Merritt (6th from Right) and Elwell S. Otis (4th from Right), and their staffs in front of Malacañan Palace, San Miguel district, Manila Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis replaced Merritt on Aug. 29, 1898. Ten days later, on September 8, he demanded that Filipino troops evacuate Manila beyond the demarcation lines marked on a map that he furnished Aguinaldo. Otis claimed that the Peace Protocol signed in Washington D.C. on August 12 between Spain and the United States gave the latter the right to occupy the bay, harbor and city of Manila. He ordered Aguinaldo to comply within a week or he would face forcible action. Aguinaldo's emissaries asked Otis to withdraw his ultimatum; when he refused, they requested him to moderate his language in a second letter. The American commander agreed.

Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis and his staff on the veranda of Malacañan Palace, San Miguel district, Manila On September 13, Otis wrote Aguinaldo an amended letter:

A Filipino regiment preparing to leave Manila On September 15, about 2,000 Filipino soldiers marched out of the zones.  They did not know of the ultimatum, but were told about the succeeding "friendly request". Their bands played American airs and they cheered for the Americans as they withdrew. They did not know of the ultimatum, but were told about the succeeding "friendly request". Their bands played American airs and they cheered for the Americans as they withdrew. Otis acceded to Aguinaldo's request that Gen. Pio del Pilar (RIGHT) and his troops continue to occupy Paco district. First, Aguinaldo asserted that Paco was traditionally outside the jurisdiction of Manila. Second, he was unable to discipline Del Pilar who would surely refuse to move out in response to his orders. [The Americans called Pio del Pilar a "fire-eater".] In any case, he would gradually withdraw his troops from the command of Del Pilar, until his force was too small to be threatening. [Twenty-five days later, on October 10, Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Anderson submitted to the Adjutant-general, US 8th Army Corps, an official complaint against Gen. Pio del Pilar: "Sir: "I have the honor to report that yesterday, the 9th instant, while proceeding up the Pasig River, on the steam launch Canacao, with three officers of my staff, the American flag flying over the boat. I was stopped by an armed Filipino guard and informed that we could go no farther. Explaining that we were an unarmed party of American officers out upon an excursion, we were informed that, by orders given two days before, no Americans, armed or unarmed. were allowed to pass up the Pasig River without a special permit from President Aguinaldo. "I demanded to see the written order, and it was brought and shown me. It was an official letter signed by Pio del Pilar. division general, written in Tagalo and stamped with what appeared to be an official seal. It purported to be issued by the authority of the president of the revolutionary government, and forbade Americans, either armed or unarmed, from passing up the Pasig River. It was signed by Pilar himself. "As this is a distinctly hostile act. I beg leave to ask how far we are to submit to this kind of interference. "It is respectfully submitted that whether this act of Pilar was authorized or not by the assumed insurgent government, it should, in any event, be resented."]

Aguinaldo's headquarters at Bacoor, Cavite Province. Photo was taken in 2006. Source:www.flickr.com/photos/15452709@N00/292183090 Aguinaldo transferred his headquarters and the seat of his government from Bacoor (ABOVE) to the inland town of Malolos, 21 miles (34 km) north of Manila on the line of the railroad. Here he was out of range of the guns of the US fleet, and in a naturally strong position.

The first American newspaper in the Philiipines, The American Soldier, reports on corruption under the old Spanish regime. This issue came out on Nov. 5, 1898. |

Jan. 23, 1899: Inauguration of the First Philippine Republic

Feb. 9, 1899: Battle of San Roque, Cavite Province

San Roque (ABOVE, in 1899) lies about 22 miles (35 km) southwest from Manila by road; a narrow artificial causeway about 600 yards (meters) in length separates it from mainland Cavite Province. [LEFT, 1896 map]. San Roque (ABOVE, in 1899) lies about 22 miles (35 km) southwest from Manila by road; a narrow artificial causeway about 600 yards (meters) in length separates it from mainland Cavite Province. [LEFT, 1896 map].

It adjoins the Cavite navy yard that fell under American control after the battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898. (In 1903, the town of San Roque was merged into Cavite Nuevo, which, in turn became Cavite City; San Roque has been reduced to a district). On the night of February 4, word reached the Americans at the yard that the Filipinos had attacked US forces in Manila . The call to arms was sounded. From across the bay the thunder of guns and the roll of volleys told that the conflict was on. The Americans expected that the Filipinos would attack them from San Roque, but they did not.

51st Iowa Volunteers in the Philippines, 1899 Immediately thereafter sentries and outposts were established at the outskirts of San Roque by a battalion of the 51st Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment under the command of Col. John T. Loper.

American outpost at San Roque, Cavite Province, 1899.

American outpost at the causeway separating San Roque and mainland Cavite Province Batteries were placed opposite the approach from the causeway separating San Roque and Cavite Nuevo. Gatling guns were placed on bastions, and field pieces were trained on the blockhouses of the Filipinos, while the gunboats Manila and Callao were anchored close inshore in readiness to lend assistance to the Americans in case it was needed.

Filipino entrenchments commanding the causeway connecting the Cavite peninsula with the mainland On the afternoon of February 8, the Americans sent 2Lt. John A. Glass, of the 1st Battalion of California Heavy Artillery (California National Guards), with a flag of truce and an escort to the Filipino commander, General Salvador Estrella, and presented him with Commodore George Dewey’s demand that the Filipinos evacuate San Roque; unless the demand was complied with before nine o'clock of the following morning, the town would be bombarded.

San Roque burns On February 9, at 7;30 a.m., a party of three, headed by the Mayor of San Roque, came over the American line and asked for further time. Commodore Dewey, who was ashore, refused, and the delegation immediately returned. A white flag was then hoisted over a Filipino blockhouse, but it was a bluff, intended to draw the advance of American troops into a trap. Shortly thereafter the town was set ablaze by the Filipinos.

Gun. No. 3 of the California Heavy Artillery shelling Filipino positions at 1,200 yards (meters), San Roque, Cavite Province.

American troops in San Roque fighting Two battalions of the 51st Iowa Volunteers, the Wyoming Light Battery and the Nevada Cavalry, with Batteries A and D of the California Heavy Artillery were dispatched across the causeway. Every passage through San Roque was a seething mass of flames, and in order to gain entrance to the town it was necessary for the Americans to flank it by moving along the seashore. The Americans fought their way through the flames of the burning town in pursuit of the retreating Filipinos, dragging their heavy guns by hand, and skirmishing whenever the opportunity afforded.

Fortifications at San Roque built by the Filipinos

Americans in San Roque battle

Filipino POWs at San Roque

Ruins of San Roque Burr Ellis, of Frazier, Valley, California, narrated what he did in San Roque, Cavite. He wrote: "They did not commence fighting over here for several days after the war commenced. Dewey gave them till nine o’clock one day to surrender, and that night they all left but a few out to their trenches, and those that they left burned up the town, and when the town commenced burning, the troops were ordered in as far as possible and said, 'Kill all we could find.' I ran off from the hospital and went ahead with the scouts. And you bet, I did not cross the ocean for the fun there was in it, so the first one I found, he was in a house, down on his knees fanning a fire, trying to burn the house, and I pulled my old Long Tom to my shoulder and left him to burn with the fire, which he did. I got his knife, and another jumped out of the window and ran, and I brought him to the ground like a jack-rabbit. I killed seven that I know of, and one more, I am almost sure of: I shot ten shots at him running and knocked him down, and that evening the boys out in front of our trenches now found one with his arm shot off at the shoulder and dead as h____. I had lots of fun that morning...."

The Wichita Daily Eagle, Feb. 10, 1899, Page 1

American guard mount at San Roque, 1899.

American officers in command at San Roque, 1899.

American troops in possession of Teatro Caviteño in Cavite Nuevo (now Cavite City). The theater was Emilio Aguinaldo's first military headquarters upon his return from Hong Kong on May 19, 1898. It was here that the Philippine national flag was hoisted for the first time on May 28, 1898 after the Filipinos defeated the Spaniards in the battle of Alapan, Imus, Cavite. The town of San Roque was merged into Cavite Nuevo in 1903.

The New York Times, issue of Feb. 10, 1899 Feb. 10, 1899: Battle of Caloocan

Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr. (central figure) and staff near Caloocan. At extreme left is Capt. Charles G. Sawtelle Jr., Asst. Quartermaster; 2nd from left is Colonel (later Brig. Gen.) Frederick Funston; 3rd from right is Maj. Putnam Bradlee Strong, Asst. Adjutant General; and 2nd from right is Maj. John Mallory, Inspector General.

After capturing La Loma, Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr. pushed toward Caloocan, an important railroad center 11 miles (17 km) north of Manila. For several days, trainloads of Filipino soldiers were seen landing in the town.

Old Spanish gun mounted by the Filipinos near Caloocan to control the railroad between Manila and Malolos. It also barred the way to Malolos, Aguinaldo's capitol. General Antonio Luna together with a Belgian-trained engineer, Jose Alejandrino had constructed trenches to defend Caloocan.

La Loma Church: General MacArthur's headquarters before the Battle of Caloocan. PHOTO was taken in February 1899.

Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr. directing the American advance on Caloocan.

20th Kansas Volunteers digging trenches just before the engagement at Caloocan

1st South Dakota Volunteers and a section of a light battery behind entrenchments just before the battle of Caloocan

Original caption: "The Montana Regiment Waiting The Order To Advance On Caloocan."

Original caption: "Idaho volunteers near Caloocan, waiting to be called to the Front" Edward Stratemayer in his article entitled UNDER OTIS IN THE PHILIPPINES described the capture of Caloocan: "On to the town! was the next cry and into the city they advanced, the Filipinos contesting every step stubbornly but unsuccessfully. A stand was taken at a church and at several public and private buildings; but the blood of the Americans was not up and they forced the rebels out, in many cases at the point of the bayonet. Compelled to give up the city, the Filipinos tried their best to burn the main portion of the town, and soon the smaller houses were a mass of flames. An attempt was also made to burn the church and the city hall, but here the Americans interferred and many of the rebels were caught and taken prisoner. The general advance had begun at one o'clock in the afternoon. At half past five, Old Glory was swung to the breeze from the flagstaff of the city hall and rebel sway in Caloocan became a thing of the past. When the smoke of war cleared out, the inhabitants of the town found their homes in ashes, the buildings razed to the ground and only the Casa Tribuna, the church, and the convent remained standing."

Original caption: "The trenches before Caloocan afforded the best test of soldierly nerve under the strain of constant expectation of attack. The guns are here being placed in position for the coming battle. The defense is admirable."

US Battery at Caloocan

1899 painting, drawn from eyewitness accounts, by G.W. Peters. Title: "The Battle Before Caloocan, February 10, 1899--View from the Chinese church". Maj. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., is the khaki-clad officer with binoculars; the battery of Utah Artillery is on the middle foreground, while the 10th Pennsylvania Volunteers occupy the ground behind the wall. This print came from the book, "Harper's Pictorial History of the War with Spain", published in 1899. Describing the Caloocan battle, Charles Bremer, of Minneapolis, Kansas, wrote: "Company I had taken a few prisoners, and stopped. The colonel ordered them up in to line time after time, and finally sent Captain Bishop back to start them. There occurred the hardest sight I ever saw. They had four prisoners, and didn’t know what to do with them. They asked Captain Bishop what to do, and he said: 'You know the orders', and four natives fell dead.” Capt. David S. Elliot, of the 20th Kansas Volunteers, said: "Talk about war being 'hell,' this war beats the hottest estimate ever made of that locality. Caloocan was supposed to contain seventeen thousand inhabitants. The Twentieth Kansas swept through it, and now Caloocan contains not one living native. Of the buildings, the battered walls of the great church and dismal prison alone remain. The village of Maypaja, where our first fight occurred on the night of the fourth, had five thousand people on that day—now not one stone remains upon top of another. You can only faintly imagine this terrible scene of desolation."

Original caption: "The Advance On Caloocan --- On The Firing-Line Of The Kansas Volunteers."

Volley firing by the 20th Kansas Volunteers, 1899

20th Kansas Volunteers advancing across an open field, 1899 Arthur Minkler, of the 20th Kansas Volunteers: ""We advanced four miles and we fought every inch of the way;... saw twenty-five dead insurgents in one place and twenty-seven in another, besides a whole lot of them scattered along that I did not count.... It was like hunting rabbits; an insurgent would jump out of a hole or the brush and run; he would not get very far.... I suppose you are not interested in the way we do the job. We do not take prisoners. At least the Twentieth Kansas do not". During the battle, the Kawit Battalion from Cavite refused to attack when given the order by Gen. Antonio Luna. Because of this, he disarmed and relieved them of their duties. Soldiers from this same Cavite battalion later assassinated Luna in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija on June 5, 1899.

Igorot POWs at Caloocan  The Igorots --- hardy mountaineers from the Cordilleras of northern Luzon island---sent a contingent of men to fight the Americans at Caloocan. The warriors were armed only with spears, axes, and shields.They were commanded by Maj. Federico Isabelo "Belong" Abaya (LEFT), a native of Candon, Ilocos Sur Province. He was a member of the Espiritu de Candon, a revolutionary group in Candon. On March 25, 1898, he led the so-called Ikkis ti Kandon (Cry of Candon), drove away the Spaniards from the town and beheaded the Spanish parish priest (Fr. Rafael Redondo) and two visiting friars. He served in the Philippine Army under General Manuel Tinio, and later became guerilla commander in southern Ilocos under Col. Juan Villamor of Bangued, Abra Province The Igorots --- hardy mountaineers from the Cordilleras of northern Luzon island---sent a contingent of men to fight the Americans at Caloocan. The warriors were armed only with spears, axes, and shields.They were commanded by Maj. Federico Isabelo "Belong" Abaya (LEFT), a native of Candon, Ilocos Sur Province. He was a member of the Espiritu de Candon, a revolutionary group in Candon. On March 25, 1898, he led the so-called Ikkis ti Kandon (Cry of Candon), drove away the Spaniards from the town and beheaded the Spanish parish priest (Fr. Rafael Redondo) and two visiting friars. He served in the Philippine Army under General Manuel Tinio, and later became guerilla commander in southern Ilocos under Col. Juan Villamor of Bangued, Abra Province

Abaya was born in 1854 to a well-to-do family and died in battle on May 3, 1900. He and 10 men were at the mountain village of Guilong, Galimuyod, 11 miles east of Candon, when they encountered a 30-man patrol of Company G, 33rd Infantry Regiment of United States Volunteers (USV). The Americans were led by 2Lt. Donald C. McClelland. Abaya died with 2 of his men and 3 were captured. There were no casualties on the American side. [Guilong has been renamed "Abaya" in honor of the hero].

Igorot POWs at Caloocan The Igorots soon fell out with the Philippine army and became U.S. allies, acting as guides for American troops in the rugged highlands of northern Luzon. A Tingguian Igorot, Januario Galut, led U.S. troops to a position where they could surround and defeat the forces of Gen. Gregorio del Pilar at Tirad Pass on Dec. 2, 1899. Many of the Igorots who served in Aguinaldo's army later joined the colonial Philippine Constabulary. The mortal combat at Caloocan killed Luna's Chief of Staff, Major Bautista of the Territorial Militia, and Captain Licero of Malolos. The Annual Report of the U.S. War Department listed 5 American dead and 45 wounded; 200 Filipinos killed and 800 wounded.

10th Pennsylvania Volunteers atop captured Filipino blockhouse

Original caption: "Flags of truce in the streets of Caloocan"

(LEFT) Caloocan Church after bombardment by Admiral George Dewey's fleet. (RIGHT) Americans set up a field telegraph station inside the church

Caloocan Church, after the battle. The American photographer wrote: "Caloocan, six miles north of Manila, bombarded by guns of the 'Charleston' and 'Monadnock' and leveled to the ground by fire, was a sorry sight as the Twentieth Kansas regiment advanced. The insurgent dead lay in great numbers for it was here that the Kansans won their first great victory. What was a prosperous town was in a few moments wiped out of existence. The church was afterwards used as headquarters."

A US soldier signals from the tower of Caloocan church to Manila Bay, spelling out a message to the monitor Monadnock over the intervening Filipino lines

Original caption: "View of Caloocan, showing burned district"

US army ambulances at Caloocan

Conveying wounded American soldier, February 1899

Trainload of dead and wounded Americans at Caloocan

Original caption: "On the road to Caloocan --- the aftermath. Photograph by Lieut. C.F. O'Keefe, U.S.A."

Dead Filipino soldier at Caloocan

Filipinos killed by the Utah Light Battery at Caloocan. Fred D. Sweet, of the Utah Light Battery: "The scene reminded me of the shooting of jack-rabbits in Utah, only the rabbits sometimes got away, but the insurgents did not." Theodore Conley, 20th Kansas Regiment: "Talk about dead Indians! Why, they are lying everywhere. The trenches are full of them...There is not a feature of the whole miserable business that a patriotic American citizen, one who loves to read of the brave deeds of the American colonists in the splendid struggle for American independence, can look upon with complacency, much less with pride. This war is reversing history. It places the American people and the government of the United States in the position occupied by Great Britain in 1776. It is an utterly causeless and defenseless war, and it should be abandoned by this government without delay. The longer it is continued, the greater crime it becomes—a crime against human liberty as well as against Christianity and civilization..."

Men of Company B, 1st Idaho Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 1899

Americans with captured Filipino smooth-bore cannon at Caloocan

The station at Caloocan, on the Manila to Dagupan railroad, captured by the Americans on Feb. 10, 1899.

Train captured from the Filipinos at Caloocan. The Americans secured 5 engines, 50 passenger coaches, and 100 freight cars. Photo was actually taken shortly before the Battle of Quingua, Bulacan Province, on April 23, 1899

The Atlanta Constitution of Georgia reports on the capture of Caloocan, issue of Feb. 11, 1899 Feb. 17, 1899: Founding of Philippine Red Cross  Emilio Aguinaldo's first wife was Hilaria del Rosario (LEFT, 1898 photo) of Imus, Cavite Province, whom he married on Jan. 1, 1896. She was born in 1877. They had five children: Miguel, Carmen, Emilio Jr., Maria and Cristina. Emilio Aguinaldo's first wife was Hilaria del Rosario (LEFT, 1898 photo) of Imus, Cavite Province, whom he married on Jan. 1, 1896. She was born in 1877. They had five children: Miguel, Carmen, Emilio Jr., Maria and Cristina.

Hilaria organized the Hijas de la Revolucion (Daughters of the Revolution), which later became the Asociacion Nacional de la Cruz Roja (National Association of the Red Cross), considered a kind of precursor of the present Philippine National Red Cross. On Feb. 17, 1899, the Malolos Republic approved the Constitution of the National Association of the Red Cross. The Republic appointed Hilaria del Rosario Aguinaldo as President of the Association. In its first five months it had thirteen chapters. She and others helped to organize and distribute the needed food and medicines to wounded Filipino soldiers. On Oct. 5, 1899, Mrs. Aguinaldo spoke to the soldiers assembled in Tarlac:  "...Were it not a shocking thing for us to wear trousers and to carry rifles ... we [the women] members of the Philippine Red Cross -- would aid you in the struggle and die by your side, for what would our lives amount to if we should still have to live in slavery? Though I am a weak woman, I can assure you that my prayer is for all the Filipino people..." She accompanied her husband in his long and arduous trek to northern Luzon, from Nov. 13, 1899 in Bayambang, Pangasinan, until Dec. 25, 1899 in Talubin, Bontoc, Mountain Province; on that Christmas day, Emilio Aguinaldo, wishing to spare the 5 women in his entourage from further hardships (Hilaria, Aguinaldo's sister, Col. Manuel Sityar's wife and Col. Jose Leyba's 2 sisters) ordered Colonel Sityar and another officer to accompany the women and surrender to the Americans in Talubin. Hilaria was reunited with her husband soon after his capture by the Americans on March 23, 1901.

Hilaria and son Miguel. Photos taken in 1901. Hilaria del Rosario Aguinaldo died of tuberculosis in Kawit, Cavite on March 6, 1921.

A view of the native hut used as a hospital during the Philippine-American War by the International Red Cross Society Francis A. Blake, of California, in charge of the Red Cross, wrote after a battle: "I never saw such execution in my life, and hope never to see such sights as met me on all sides as our little corps passed over the field, dressing wounded. Legs and arms nearly demolished; total decapitation; horrible wounds in chests and abdomens, showing the determination of our soldiers to kill every native in sight. The Filipinos did stand their ground heroically, contesting every inch, but proved themselves unable to stand the deadly fire of our well-trained and eager boys in blue. I counted seventy-nine dead natives in one small field, and learn that on the other side of the river their bodies were stacked up for breastworks." The War in the Visayas, Feb. 11, 1899 - March 10, 1899

On Feb. 11, 1899, the US First Separate Brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Marcus P. Miller, West Point Class 1858, invaded Iloilo City (ABOVE, in 1899) on Panay Island. The defenders were led by General Martin Delgado and Teresa "Nay Isa" Magbanua y Ferraris, the Visayan "Joan of Arc".