|

|

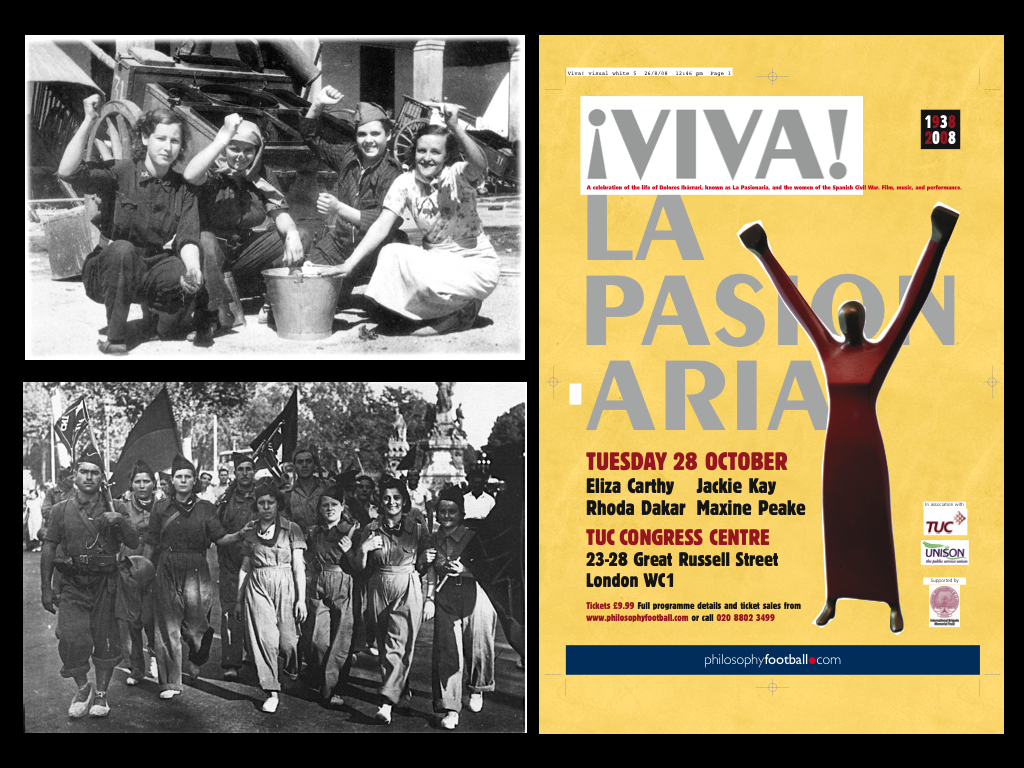

| Spanish Civil War 2011 marks the 75th anniversary of the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and a series of events are being held to commemorate the occasion. Available information suggests that there were about 500,000 deaths from all causes during the Spanish Civil War. An estimated 200,000 died from combat-related causes. Of these, 110,000 fought for the Republicans and 90,000 for the Nationalists. This implies that 10 per cent of all soldiers who fought in the war were killed. It has been calculated that the Nationalist Army executed 75,000 people in the war whereas the Republican Army accounted for 55,000. These deaths takes into account the murders of members of rival political groups. It is estimated that about 5,300 foreign soldiers died while fighting for the Nationalists (4,000 Italians, 300 Germans, 1,000 others). The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the war. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others). Around 10,000 Spanish people were killed in bombing raids. The vast majority of these were victims of the German Condor Legion. The economic blockade of Republican controlled areas caused malnutrition in the civilian population. It is believed that this caused the deaths of around 25,000 people. All told, about 3.3 per cent of the Spanish population died during the war with another 7.5 per cent being injured. After the war it is believed that the government of General Francisco Franco arranged the executions of 100,000 Republican prisoners. It is estimated that another 35,000 Republicans died in concentration camps in the years that followed the war. | Then&now - 1936: Spanish Civil War: After the bombing Spanish civil war: after the bombing of Gran Via avenue, in Madrid, from Franco´s army positions (in Casa de Campo park, out of the city, 5-6 kms far).

From 1934 to 1936, the Second Spanish Republic was governed by a center-right coalition that included the conservative Catholic Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA). During this time, there were general strikes in Valencia and Zaragoza, street conflicts in Madrid and Barcelona, and a miners' uprising in Asturias, which was put down forcefully by the troops commanded by General López Ochoa and the Legionnaires commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Juan Yagüe, under the direction of Minister of War Diego Hidalgo. During this time, the government expended great efforts to annul the social gains that had been made in the previous years, especially in agrarian reform. After a series of governmental crises, the elections of February 16, 1936, brought to power a Popular Front government supported by the parties of the left and opposed by those of the right and center. |

| | |

|

Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War Bristol RefugeesThe Spanish Civil War, between Franco's right-wing Nationalists and the left-wing Republicans, started 70 years ago today. But not many people know about the story of how a group of Spanish schoolchildren fled Spain and sought refuge in Bristol. Refugees: With fierce fighting in their native Basque region of Spain, dozens of children were evacuated to the safety of Bristol. The Spanish Civil War was a vicious conflict which killed thousands and divided not only the Spaniards, but people all over Europe. The war attracted worldwide attention from those who saw it as a straightforward battle between Socialism and Fascism. Many were rightly fearful that it would lead to the world war which followed it. Bristol people were involved in the war on many levels, with four young men even giving their lives for the Republican cause in Spain. Even those who remained in Bristol were reminded of the appalling danger the war posed to the civilians of Spain when 51 Basque refugees arrived in the city back in 1936. The children had been sent by anxious parents who wanted them removed from a land of warring factions, political murder and appalling civil strife. The late Gladys Parsons and her husband Graham knew very little about the rights and wrongs of the war when, in that year, Graham was offered a temporary job as a caretaker at No 10 Kingsdown Parade by Bristol Education Committee. It was a time of poverty and depression and Graham, an out-of- work electrician, took the job at what had been the Bristol School for deaf children (the building was lost in a wartime blitz). Gladys told the Post in 1986: 'It must have been the spring of 1936 when the children arrived. 'We all lived in this beautiful old house in Kingsdown and the children seemed happy enough. I remember my husband used to play football with them on the lovely lawns outside.' Her own children, Geoffrey and Sheila, became friends with the little Spanish refugees, and the people of Bristol rallied around, taking the youngsters on trips and parties. 'I can still remember some names,' recalled Gladys. 'Hortensia and Erisa were the teachers, and there was Maria and one little girl whose hair they had dyed blonde and whom everyone called Shirley Temple. 'The only boy's name I can remember was Alfonso. Most of the children came from the Bilbao area of Spain, I believe.' There were many happy memories. 'It was marvellous how volunteers responded, always ready and willing to take the children on excursions,' explained Gladys. 'They once took them to Blaise, and sometimes on days out to Weston- super-Mare.' Volunteers included the Coles family of Shirehampton. The late Charles Coles, a foreman stevedore with C J King's at Avonmouth docks, even played Father Christmas for the children. His daughter Olive told the Post in 1986: 'I remember the vitality of the children. I was 10 years old and remember going over by train from Shirehampton to see them. 'The one I remember in particular was Maria, such a little one and such fun. She even dared me to defy my father which was something I would never have dreamed of doing. He was very Victorian' 'We dressed up and took toys over to them for their Christmas party. No, they weren't sad or homesick. They were very happy children.' But the children were always thinking of home and their families in Spain, as Graham Parsons discovered one day when he went to clear the boilers in Kingsdown Parade. Trying to shovel out left-over ash, he found that the space was jammed packed with tinned food. The children said that they had hidden it because there was nothing like this in Spain and they wanted their families to have some when they went home. After several months, with the worst of the fighting over, the children returned to their homes and families. Mrs Parsons said: 'I never heard from any of them ever again, but I do think about them. I do wonder what happened to them, and I do like to remember their time here in Bristol, and think about what they must be like now. ' The children's story is really just a footnote in history, but one which illustrates just how disturbing events must have been to those who lived through them. So profound was the experience of the war that it inspired some of the 20th century's greatest artists to write some of their most moving work. George Orwell's masterpiece, Homage To Catalonia, was written about his experiences of the war, as was Ernest Hemingway's For Whom The Bell Tolls and Laurie Lee's A Moment Of War. It also inspired Pablo Picasso's famous painting Guernica, which commemorated the horrifying bomb attack on that city's civilian population. Others sent money, campaigned to raise awareness and lobbied the British government to help where it could. Bristol East, the constituency of 'Iron Chancellor' Stafford Cripps, had been the radical centre of Labour Party agitation for years and young Bristol Socialists there were determined to do what they could to end the suffering. It was a time of mass unemployment, when Oswald Mosley's right-wing Blackshirts, were on the rise. So the election of the left-wing Spanish Popular Front Government in 1936, which was dominated by the Socialist Republican party, made a big impact. When Franco and his fellow- conspirators rose up against them, the Labour League of Youth in Bristol flung itself into a frenzy of activity, organising propaganda and sending money and food to Spain. The old Empire and Olympia theatres saw massive Sunday night meetings with national speakers and regular collections were made at Bristol's largest factories, including Fry's and Wills', for an ambulance which the Bristol campaign bought in August 1937. Street meetings and collections were held every weekend on the Downs and Welsh Back. Of the young men and women prepared to go off to Spain to take part in the conflict, some joined the International Brigades and others the Spanish anarchist group POUM. In Castle Park, there's a plaque commemorating four young Bristol men who lost their lives in the civil war. It reads: 'This plaque was erected by Bristol City Council to commemorate those British volunteers who fought with the Republican Army in the Spanish Civil War. 'The 526 volunteers from Britain who gave their lives in the fight to defend democracy included four men from Bristol. They died for liberty.' The plaque then lists their names - W G Boyce, J Burton, L Huson and T E Stephens, who died between February 1937 and May 1938. It was unveiled in 1986 by trade union leader Jack Jones, who himself was a former member of the International Brigade. IT'S always a gamble to reread the books one loved in youth. Most of Fitzgerald still holds up, but Thomas Wolfe is virtually unreadable. J. D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye turns out to be as good as I remembered it, but Franny and Zooey is unbearably cute. Scribner has recently reissued in hardcover Ernest Hemingway's four major works -- The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and The Old Man and the Sea -- and I made my way through them again, mesmerized by Hemingway's genius as a storyteller and alarmed by the vicissitudes of his prose. The discrepancy between eloquence and maudlin self-indulgence was often visible on a single page; I never knew when he would soar and when he would lapse into the fabled macho pose that has proved so irresistible to parody. (I especially recommend Dwight Macdonald's essay in Against the American Grain, which begins: "He was a big man with a bushy beard and everybody knew him.") But there is something moving about this uneven achievement; Hemingway's tremendous vulnerability and his dogged efforts to master it, to push on at whatever cost, gave his life and work a terrible pathos. Then Alfonso XIII of Spain assumed power in 1902. Alfonso XIII became increasingly autocratic and in 1909 was condemned for ordering the execution of the radical leader, Ferrer Guardia, in Barcelona. He also prevented liberal reforms being introduced before the First World War. Blamed for the Spanish defeat in the Moroccan War (1921) Alfonso was in constant conflict with Spanish politicians. His anti-democratic views encouraged Miguel Primo de Rivera to lead a military coup in 1923. He promised to eliminate corruption and to regenerate Spain. In order to do this he suspended the constitution, established martial law and imposed a strict system of censorship. Miguel Primo de Rivera initially said he would rule for only 90 days, however, he broke this promise and remained in power. Little social reform took place but he tried to reduce unemployment by spending money on public works. To pay for this Primo de Rivera introduced higher taxes on the rich. When they complained he changed his policies and attempted to raise money by public loans. This caused rapid inflation and after losing support of the army was forced to resign in January 1930. In 1931 Alfonso XIII agreed to democratic elections. It was the first time for nearly sixty years that free elections had been allowed in Spain. When the Spanish people voted overwhelmingly for a republic, Alfonso was advised that the only way to avoid large-scale violence was to go into exile. Alfonso agreed and left the country on 14th April, 1931. The provisional government of the Second Republic called a general election for June 1931. The Socialist Party (PSOE) and other left wing parties won an overwhelming victory. Niceto Alcala Zamora, a moderate Republican, became prime minister, but included in his cabinet several radical figures such as Manuel Azaña, Francisco Largo Caballero and Indalecio Prieto. On 16th October 1931, Azaña replaced Niceto Alcala Zamora as prime minister. With the support of the Socialist Party (PSOE) he attempted to introduce agrarian reform and regional autonomy. However, these measures were blocked in the Cortes. Azaña believed that the Catholic Church was responsible for Spain's backwardness. He defended the elimination of special privileges for the Church on the grounds that Spain had ceased to be Catholic. Azaña was criticized by the Catholic Church for not doing more to stop the burning of religious buildings in May 1931. He controversially remarked that burning of "all the convents in Spain was not worth the life of a single Republican". The failed military coup led by José Sanjurjo on 10th August, 1932, rallied support for Azaña's government. It was now possible for him to get the Agrarian Reform Bill and the Catalan Statute passed by the Cortes. However, the modernization programme of the Azaña administration was undermined by a lack of financial resources. The November 1933 elections saw the right-wing CEDA party win 115 seats whereas the Socialist Party only managed 58. CEDA now formed a parliamentary alliance with the Radical Party. Over the next two years the new administration demolished the reforms that had been introduced by Manuel Azaña and his government. This led to a general strike on 4th October 1934 and an armed rising in Asturias. Azaña was accused of encouraging these disturbances and on 7th October he was arrested and interned on a ship in Barcelona Harbour. However, no evidence could be found against him and he was released on 18th December. Azaña was also accused of supplying arms to the Asturias insurrectionaries. In March 1935, the matter was debated in the Cortes, where Azaña defended himself in a three-hour speech. On 6th April, 1935, the Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees acquitted Azaña. On 15th January 1936, Manuel Azaña helped to establish a coalition of parties on the political left to fight the national elections due to take place the following month. This included the Socialist Party (PSOE), Communist Party ( PCE), Esquerra Party and the Republican Union Party. The Popular Front, as the coalition became known, advocated the restoration of Catalan autonomy, amnesty for political prisoners, agrarian reform, an end to political blacklists and the payment of damages for property owners who suffered during the revolt of 1934. The Anarchists refused to support the coalition and instead urged people not to vote. Right-wing groups in Spain formed the National Front. This included the CEDA and the Carlists. The Falange Española did not officially join but most of its members supported the aims of the National Front. The Spanish people voted on Sunday, 16th February, 1936. Out of a possible 13.5 million voters, over 9,870,000 participated in the 1936 General Election. 4,654,116 people (34.3) voted for the Popular Front, whereas the National Front obtained 4,503,505 (33.2) and the centre parties got 526,615 (5.4). The Popular Front, with 263 seats out of the 473 in the Cortes formed the new government. The Popular Front government immediately upset the conservatives by releasing all left-wing political prisoners. The government also introduced agrarian reforms that penalized the landed aristocracy. Other measures included transferring right-wing military leaders such as Francisco Franco to posts outside Spain, outlawing the Falange Española and granting Catalonia political and administrative autonomy. In February 1936 Franco joined other Spanish Army officers, such as Emilio Mola, Juan Yague, Gonzalo Queipo de Llano and José Sanjurjo, in talking about what they should do about the Popular Front government. Mola became leader of this group and at this stage Franco was unwilling to fully commit himself to joining any possible uprising. As a result of the government's policies the wealthy took vast sums of capital out of the country. This created an economic crisis and the value of the peseta declined which damaged trade and tourism. With prices rising workers demanded higher wages. This situation led to a series of strikes in Spain. On the 10th May 1936 the conservative Niceto Alcala Zamora was ousted as president and replaced by the left-wing Manuel Azaña. Soon afterwards Spanish Army officers began plotting to overthrow the Popular Front government. President Manuel Azaña appointed Diego Martinez Barrio as prime minister on 18th July 1936 and asked him to negotiate with the rebels. He contacted Emilio Mola and offered him the post of Minister of War in his government. He refused and when Azaña realized that the Nationalists were unwilling to compromise, he sacked Martinez Barrio and replaced him with José Giral. To protect the Popular Front government, Giral gave orders for arms to be distributed to left-wing organizations that opposed the military uprising. General Emilio Mola issued his proclamation of revolt in Navarre on 19th July, 1936. The coup got off to a bad start with José Sanjurjo being killed in an air crash on 20th July. The uprising was a failure in most parts of Spain but Mola's forces were successful in the Canary Islands, Morocco, Seville and Aragon. Francisco Franco, now commander of the Army of Africa, joined the revolt and began to conquer southern Spain. Manuel Azaña had no desire to be head of a government that was trying to militarily defeat another group of Spaniards. He attempted to resign but was persuaded to stay on by the Socialist Party and Communist Party who hoped that he was the best person to persuade foreign governments not to support the military uprising. Socialists and Communists all over Europe formed International Brigades and went to Spain to protect the Popular Front government. Men who fought with the Republican Army included George Orwell, André Marty, Christopher Caudwell, Jack Jones, Len Crome, Oliver Law, Tom Winteringham, Joe Garber, Lou Kenton, Bill Alexander, David Marshall, Alfred Sherman, William Aalto, Hans Amlie, Bill Bailey, Robert Merriman, Steve Nelson, Walter Grant, Alvah Bessie, Joe Dallet, David Doran, John Gates, Harry Haywood, Oliver Law, Edwin Rolfe, Milton Wolff, Hans Beimler, Frank Ryan, Emilo Kléber, Ludwig Renn, Gustav Regler, Ralph Fox, Sam Wild and John Cornford. Men came from a variety of left-wing groups but the International Brigades were nearly always led by Communists. This created problems with other Republican groups such as the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) and the Anarchists. In 1936 the Spanish Army had two distinct forces: The Peninsular Army and the Army of Africa. The Peninsular Army had 8,851 officers and 112,228 men. It was considered to be poorly trained force and on the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War over 40,000 men were on leave. It is estimated that 4,660 officers and 19,000 men joined the Nationalist forces in the struggle with the Republicans. Of the remaining 4,191 officers, around 2,000 supported the Popular Front government. The Army of Africa was considered to be superior to the Peninsular Army. It consisted of those Spanish Army units based in Morocco. In 1936 the force numbered 34,047 men and was composed of regular Spanish Army units and the Spanish Foreign Legion. On 19th July, 1936, General Francisco Franco assumed command of this force and organized its airlift to Spain. During the first two months of the war, around 10,500 men were flown across the Straits of Gibraltar by aircraft owned by the Luftwaffe. Others followed and the Army of Africa played an important role in gaining Nationalist control of South-Western Spain. There were also two internal paramilitary police forces: the Civil Guard and the Assault Guard. The Civil Guard, an elite paramilitary police force, had 69,000 men and officers. It is estimated that 42,000 joined the Nationalists and 27,000 remained with the Popular Front government. The Assault Guard had around 30,000 men. Of these, only 3,500 refused to join the Nationalist uprising. It is estimated that the Republican government retained the loyalty of about half the soldiers in the Spanish Army. However, only a small percentage of the officers refused to fight with the Nationalist Army. These were often members of the left-wing Union Militar Republican Antifascisca (UMRA). Soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War the Republican Army was about one-third larger than the Nationalist Army. However, by the time the rest of the Army of Africa arrived in mainland Spain, the figures were close to equal. In the early stages of the war, members of the Falange Española, Carlists and other right-wing political parties joined the Nationalist Army. After the first few weeks of the war the Nationalist Army controlled in the north of Spain the provinces of Galicia, León, Navarre and large parts of Old Castile and Aragón. In the south they held Cádiz, Seville, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva and Cáceres. Overall, the Nationalists controlled about a third of the land in Spain. In the summer of 1936 General Emilio Mola calculated that the Nationalist Army had 100,000 in the northern sector and 60,000 in the south. On 26th August, 1936, the Nationalist authorities introduced conscription. This enabled them to recruit some 270,000 men during the next six months. On the outbreak of the war Madrid was under the control of the Popular Front government. Emilio Mola and Francisco Franco were anxious to capture the capital city of Spain as soon as possible. The first bombing raids by the Nationalist airforce began on 28th August, 1936. In September 1936, Lieutenant Colonel Walther Warlimont of the German General Staff arrived as the German commander and military adviser to General Francisco Franco. The following month Warlimont suggested that a German Condor Legion should be formed to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The initial force consisted a Bomber Group of three squadrons of Ju-52 bombers; a Fighter Group with three squadrons of He-51 fighters; a Reconnaissance Group with two squadrons of He-99 and He-70 reconnaissance bombers; and a Seaplane Squadron of He-59 and He-60 floatplanes. General Hugo Sperrle was appointed commander of the Condor Legion in November 1936. His chief of staff was Wolfram von Richthofen, the cousin of the First World War flying ace, Manfred von Richthofen. Wilhelm von Thoma was placed in charge of all German ground troops in the war. The Condor Legion was initially equipped with around 100 aircraft and 5,136 men but by the end of the war over 19,000 Germans had fought alongside the Nationalist Army. Badajoz, a Spanish province on the border with Portugal, was controlled by the Republican Army during the early days of the Spanish Civil War. General Juan de Yagüe and 3,000 troops attacked Badajoz City, in August, 1936. Bitter street fighting took place when the Nationalist Army entered the city. Losses were heavy on both sides and when the Nationalists took control of Badajoz it was claimed they massacred around 1,800 people. He also encouraged his troops to rape supporters of the Popular Front government. As a result Yagüe became known as "The Butcher of Badajoz". On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War the President Antonio Salazar of Portugal immediately supported the Nationalists in the struggle against the Popular Front government in Spain. Salazar feared that if the Republicans won the war his own authoritarian government would be under threat. Salazar, concerned about the effect the events in Spain would have on his country, established a new militia that could serve as an auxiliary police. This new police force arrested dissidents and removed politically unreliable people from educational and governmental institutions. Salazar's police also arrested supporters of the Popular Front government living in Portugal. He also sealed off the Portuguese frontier to Republicans. Although he came under considerable pressure from Britain and France, Salazar refused to allow international observers being stationed on the Portugal-Spain border. Officially he claimed that it would be a violation of Portugal sovereignty while in reality he did not want the world to know about the large amounts of military aid that was crossing into Spain. In September 1936, President Azaña appointed the left-wing socialist, Francisco Largo Caballero as prime minister. Largo Caballero also took over the important role of war minister. Largo Caballero brought into his government two left-wing radicals, Angel Galarza (minister of the interior) and Alvarez del Vayo (minister of foreign affairs). He also included four anarchists, Juan Garcia Oliver (Justice), Juan López Sánchez (Commerce), Federica Montseny (Health) and Juan Peiró (Industry) and two right-wing socialists, Juan Negrin (Finance) and Indalecio Prieto (Navy and Air) in his government. Largo Caballero also gave two ministries to the Communist Party (PCE): Jesus Hernández (Education) and Vicente Uribe (Agriculture). After taking power Francisco Largo Caballero concentrated on winning the war and did not pursue his policy of social revolution. In an effort to gain the support of foreign governments, he announced that his administration was "not fighting for socialism but for democracy and constitutional rule." Largo Caballero introduced changes that upset the left in Spain. This included conscription, the reintroduction of ranks and insignia into the militia, and the abolition of workers' and soldiers' councils. He also established a new police force, the National Republican Guard. He also agreed for Juan Negrin to be given control of the Carabineros. By the end of September 1936, the generals involved in the military uprising came to the conclusion that Francisco Franco should become commander of the Nationalist Army. He was also appointed chief of state. General Emilio Mola agreed to serve under him and was placed in charge of the Army of the North. Franco now began to remove all his main rivals for the leadership of the Nationalist forces. Some were forced into exile and nothing was done to help rescue José Antonio Primo de Rivera from captivity. However, when José Antonio was shot by the Republicans in November 1936, Franco exploited his death by making him a mythological saint of the fascist movement. By the 1st November 1936, 25,000 Nationalist troops under General Jose Varela had reached the western and southern suburbs of Madrid. Five days later he was joined by General Hugo Sperrle and the Condor Legion. This began the siege of Madrid that was to last for nearly three years. Francisco Largo Caballero and his government decided to leave Madrid on 6th November, 1936. This decision was criticized by the four anarchists in his cabinet who regarded leaving the capital as cowardice. At first they refused to go but were eventually persuaded to move to Valencia with the rest of the government. Largo Caballero appointed General José Miaja as commander of the Republican Army in Madrid. He was given instructions to set up a Junta de Defensa (Defence Council), made up of all the parties of the Popular Front, and to defend Madrid "at all costs". He was aided by his chief of staff, Vicente Rojo. Miaja's task was helped by the arrival of the International Brigades. The first units reached Madrid on 8th November. Led by the Soviet General, Emilo Kléber, the 11th International Brigade was to play an important role in the defence of the city. The Thaelmann Battalion, a volunteer unit that mainly consisted of members of the German Communist Party and the British Communist Party, was also deployed to defend the city. On 14th November Buenaventura Durruti arrived in Madrid from Aragón with his Anarchist Brigade. Within a week of arriving Durruti was killed while fighting on the outskirts of the city. Durruti's supporters in the CNT were quick to complain that he had been murdered by members of the Communist Party (PCE). On 13th December 1936, the Nationalists attempted to cut the Madrid-La Coruna road to the north-east of Madrid. After suffering heavy losses the offensive was brought to an end over Christmas. On 5th January 1937, the attack was resumed. During the next four days the Nationalist gained ten kilometres of road and lost around 15,000 men. The International Brigades, defending the road, also suffered heavy losses during this battle. In December 1936, Benito Mussolini also began to supply the Nationalists with men and equipment. This included 30,000 men from the Blue Shirts militia and 20,000 soldiers serving with the Italian Army. In March 1937 these men were incorporated into the Italian Corps (CTV). After failing to take Madrid by frontal assault General Francisco Franco gave orders for the road that linked the city to the rest of Republican Spain to be cut. A Nationalist force of 40,000 men, including men from the Army of Africa, crossed the Jarama River on 11th February. General José Miaja sent three International Brigades including the Dimitrov Battalion and the British Battalion to the Jarama Valley to block the advance. On 12th February, at what became known as Suicide Hill, the Republicans suffered heavy casualties. Tom Winteringham, the British commander, was forced to order a retreat back to the next ridge. The Nationalist then advanced up Suicide Hill and were then routed by Republican machine-gun fire. However, on the right flank, the Nationalists forced the Dimitrov Battalion to retreat. This enabled the Nationalists to virtually surround the British Battalion. Coming under heavy fire the British, now only 160 out of the original 600, had to establish defensive positions along a sunken road. Unwilling to attack again, the Nationalist Army retreated. General Francisco Franco came under pressure from Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to obtain a quick victory by taking Madrid. He eventually decided to use 30,000 Italians and 20,000 legionnaires to attack Guadalajara, forty miles northeast of the capital. On 8th March the Italian Corps took Guadalajara and began moving rapidly towards Madrid. Four days later the Republican Army with Soviet tanks counter-attacked. The Italians suffered heavy losses and those left alive were forced to retreat on 17th March. The Republicans also captured documents which proved that the Italians were regular soldiers and not volunteers. However, the Non-Intervention Committee refused to accept the evidence and the Italian government boldly announced that no Italian soldiers would be withdrawn until the Nationalist Army was victorious. On 19th April 1937, Franco forced the unification of the Falange Española and the Carlists with other small right-wing parties to form the Falange Española Tradicionalista. Franco then had himself appointed as leader of the new organisation. Imitating the tactics of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, giant posters of Franco and the dead José Antonio were displayed along with the slogan, "One State! One Country! One Chief! Franco! Franco! Franco!" all over Spain. Francisco Largo Caballero came under increasing pressure from the Communist Party to promote its members to senior posts in the government. He also refused their demands to suppress the Worker's Party (POUM) in May 1937. The Communists now withdrew from the government. In an attempt to maintain a coalition government, President Manuel Azaña sacked Largo Caballero and asked Juan Negrin to form a new cabinet. Negrin now began appointing members of the Communist Party (PCE) to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history." During the Spanish Civil War the National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT), the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and the Worker's Party (POUM) played an important role in running Barcelona. This brought them into conflict with other left-wing groups in the city including the Union General de Trabajadores (UGT), the Catalan Socialist Party (PSUC) and the Communist Party (PCE). On the 3rd May 1937, Rodriguez Salas, the Chief of Police, ordered the Civil Guard and the Assault Guard to take over the Telephone Exchange, which had been operated by the CNT since the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. Members of the CNT in the Telephone Exchange were armed and refused to give up the building. Members of the CNT, FAI and POUM became convinced that this was the start of an attack on them by the UGT, PSUC and the PCE and that night barricades were built all over the city. Fighting broke out on the 4th May. Later that day the anarchist ministers, Federica Montseny and Juan Garcia Oliver, arrived in Barcelona and attempted to negotiate a ceasefire. When this proved to be unsuccessful, Juan Negrin, Vicente Uribe and Jesus Hernández called on Francisco Largo Caballero to use government troops to takeover the city. Largo Caballero also came under pressure from Luis Companys not to take this action, fearing that this would breach Catalan autonomy. On 6th May death squads assassinated a number of prominent anarchists in their homes. The following day over 6,000 Assault Guards arrived from Valencia and gradually took control of Barcelona. It is estimated that about 400 people were killed during what became known as the May Riots. These events in Barcelona severely damaged the Popular Front government. Communist members of the Cabinet were highly critical of the way Francisco Largo Caballero handled the May Riots. President Manuel Azaña agreed and on 17th May he asked Juan Negrin to form a new government. Negrin was a communist sympathizer and from this date Joseph Stalin obtained more control over the policies of the Republican government Negrin's government now attempted to bring the Anarchist Brigades under the control of the Republican Army. At first the Anarcho-Syndicalists resisted and attempted to retain hegemony over their units. This proved impossible when the government made the decision to only pay and supply militias that subjected themselves to unified command and structure. Negrin also began appointing members of the Communist Party (PCE) to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history." In the Asturias campaign in September 1937, Adolf Galland of the Condor Legion experimented with new bombing tactics. This became known as carpet bombing (dropping all bombs on the enemy from every aircraft at one time for maximum damage). In April 1938 the Nationalist Army broke through the Republican defences and reached the sea. General Francisco Franco now moved his troops towards Valencia with the objective of encircling Madrid and the central front. Juan Negrin, in an attempt to relieve the pressure on the Spanish capital, ordered an attack across the fast-flowing Ebro. General Juan Modesto, a member of the Communist Party (PCE), was placed in charge of the offensive. Over 80,000 Republican troops, including the 15th International Brigade and the British Battalion, began crossing the river in boats on 25th July. The men then moved forward towards Corbera and Gandesa. On 26th July the Republican Army attempted to capture Hill 481, a key position at Gandesa. Hill 481 was well protected with barbed wire, trenches and bunkers. The Republicans suffered heavy casualties and after six days was forced to retreat to Hill 666 on the Sierra Pandols. It successfully defended the hill from a Nationalist offensive on 23rd September but once again large numbers were killed. The following day, Juan Negrin, head of the Republican government, announced that the International Brigades would be unilaterally withdrawn from Spain. That night the volunteers moved back across the River Ebro and began their journey out of the country. The rest of the Republican Army remained and had to endure continuous attacks from the Condor Legion. General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano also brought forward 500 cannon which fired an average of 13,500 rounds a day at the Republicans. By the middle of November, the Republicans were forced to retreat. During the battle of Ebro the Nationalist Army had 6,500 killed and nearly 30,000 wounded. These were the worst casualties of the war but it finally destroyed the Republican Army as an effective fighting force. Juan Negrin attempted to gain the support of western governments by announcing his plan to decollectivize industries. On 1st May 1938 Negrin published a thirteen-point program that included the promise of full civil and political rights and freedom of religion. In August 1938 President Manuel Azaña attempted to oust Juan Negrin. However, he no longer had the power he once had and with the support of the communists in the government and armed forces, Negrin was able to survive. On 26th January, 1939, Barcelona fell to the Nationalist Army. Azaña and his government now moved to Perelada, close to the French border. With the nationalist forces still advancing, Azaña and his colleagues crossed into France. On 27th February, 1939, the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain recognized the Nationalist government headed by General Francisco Franco. Later that day Manuel Azaña resigned from office, declaring that the war was lost and that he did not want Spaniards to make anymore useless sacrifices. Juan Negrin now promoted communist leaders such as Antonio Cordon, Juan Modesto and Enrique Lister to senior posts in the army. Segismundo Casado, commander of the Republican Army of the Centre, now became convinced that Negrin was planning a communist coup. On 4th March, Casedo, with the support of the socialist leader, Julián Besteiro and disillusioned anarchist leaders, established an anti-Negrin National Defence Junta. On 6th March José Miaja in Madrid joined the rebellion by ordering the arrests of Communists in the city. Negrin, about to leave for France, ordered Luis Barceló, commander of the First Corps of the Army of the Centre, to try and regain control of the capital. His troops entered Madrid and there was fierce fighting for several days in the city. Anarchists troops led by Cipriano Mera, managed to defeat the First Corps and Barceló was captured and executed. Segismundo Casado now tried to negotiate a peace settlement with General Francisco Franco. However, he refused demanding an unconditional surrender. Members of the Republican Army still left alive, were no longer willing to fight and the Nationalist Army entered Madrid virtually unopposed on 27th March. Four days later Francisco Franco announced the end of the Spanish Civil War. Available information suggests that there were about 500,000 deaths from all causes during the Spanish Civil War. An estimated 200,000 died from combat-related causes. Of these, 110,000 fought for the Republicans and 90,000 for the Nationalists. This implies that 10 per cent of all soldiers who fought in the war were killed. It has been calculated that the Nationalist Army executed 75,000 people in the war whereas the Republican Army accounted for 55,000. These deaths takes into account the murders of members of rival political groups. It is estimated that about 5,300 foreign soldiers died while fighting for the Nationalists (4,000 Italians, 300 Germans, 1,000 others). The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the war. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others). Around 10,000 Spanish people were killed in bombing raids. The vast majority of these were victims of the German Condor Legion. The economic blockade of Republican controlled areas caused malnutrition in the civilian population. It is believed that this caused the deaths of around 25,000 people. All told, about 3.3 per cent of the Spanish population died during the war with another 7.5 per cent being injured. After the war it is believed that the government of General Francisco Franco arranged the executions of 100,000 Republican prisoners. It is estimated that another 35,000 Republicans died in concentration camps in the years that followed the war. for someone who never actually fought in either World War I or the Spanish Civil War. The logistics of troop movements, the panic of soldiers and fleeing peasants, the contrast between the natural beauty of the countryside and the ruin war inflicts: it was when Hemingway was working with a large canvas that he was most effective. The shelling, the wounded on stretchers, the caravans of trucks moving through the mountains in A Farewell to Arms, have a lurid, Goyaesque clarity: The wounded were coming into the post, some were carried on stretchers, some walking and some were brought on the backs of men that came across the field. They were wet to the skin and all were scared. We filled two cars with stretcher cases as they came up from the cellar of the post and as I shut the door of the second car and fastened it I felt the rain on my face turn to snow. The flakes were coming heavy and fast in the rain.Here the syntax spills forward with scarcely a qualifying adjective, depending for its effect on repetition and on strong monosyllabic verbs. Henry's portentous musings on the futility of war seem fatuous beside his clear-eyed account of how war looks. A Farewell to Arms is narrated in the first person; For Whom the Bell Tolls, published eleven years later, is told by a whole cast of characters -- Robert Jordan, Jordan's lover, Maria, the peasants enlisted to help Jordan blow a bridge, a famous revolutionary, various Loyalist officers, even a fascist lieutenant. The novel shifts effortlessly from voice to voice, enabling Hemingway to portray the war from every side. Jordan's is the least plausible of these voices; it's the peasants who bring home the courage and terror latent in every skirmish. The meanspiritedness that spoils Hemingway's letters and his memoir, A Moveable Feast, is nowhere in evidence. For those who were no threat -- soldiers, peasants, doomed revolutionaries -- Hemingway was capable of unaffected sympathy, and his intuitions about what they must have gone through constitute a radical imaginative feat. The scene where a few guerrillas make their last stand on a hilltop, fending off a battalion of fascists only to perish when planes are brought in to bomb them from above, is nearly unbearable to read. Praying madly, firing at the strafing planes, they're caught at the very moment of death: Then, through the hammering of the gun, there was the whistle of the air splitting apart and then in the red black roar the earth rolled under his knees and then waved up to hit him in the face and then dirt and bits of rock were falling all over and Ignacio was lying on him and the gun was lying on him. But he was not dead because the whistle came again and the earth rolled under him with the roar. Then it came again and the earth lurched under his belly and one side of the hilltop rose into the air and then fell slowly over them where they lay.Hemingway's terse valediction is a masterpiece of indirect summary: "The planes came back three times and bombed the hilltop but no one on the hilltop knew it. For Whom the Bell Tolls made Hemingway a hero of the left in Spain, but he was too shrewd an artist to write a partisan book. The fascist lieutenant who storms the hill is given equal time to brood about how war is hell, and when, on the last page, Jordan lies dying behind a tree, submachine gun at the ready to take a few fascists with him, who should ride into view but this same lieutenant. Men are men, and both sides suffer equally: a hackneyed truth, perhaps, but a profound one. The active participants in the war covered the entire gamut of the political positions and ideologies of the time. The Nationalist side included the fascists of the Falange, Carlist and Legitimist monarchists, and Spanish nationalists and most conservatives. On the Republican side were most liberals, Basque and Catalan nationalists, socialists, Stalinist and Trotskyist communists, and anarchists of varying ideologies. To look at the breakdown another way, the Nationalists included the majority of the Catholic clergy and of practicing Catholics (outside of the Basque region), important elements of the army, the majority of landowners and many businessmen. The Republicans included most urban workers, peasants, and much of the educated middle class, especially those who were not entrepreneurs. The leaders of the rebellion were the generals Francisco Franco, Emilio Mola and José Sanjurjo. Sanjurjo was the unquestioned leader of the uprising, but he was killed in a plane crash on July 20 as he was going to Spain to take control of the rebel side. Franco, the overall commander of the Spanish army since 1933 and already a noted pro-Fascist, flew from the Canary Islands to the Spanish colonies in Morocco and took command there. For the remaining three years of the war, Franco was effective commander of all the Nationalists, and he unassumingly arranged events (including assigning missions to political rivals that would likely get them killed) so that at the end of the war there would be no opposition to his rule. One of the principal motives claimed at the time of the initial Nationalist uprising was to confront the anticlericalism of the Republican regime and to defend the Roman Catholic Church, which was censured for its support for the monarchy and which many on the Republican side blamed for the ills of the country. In the opening days of the war, churches, convents and other religious buildings were burnt without action on the part of the Republican authorities to prevent it. Articles 24 and 26 of the Constitution of the Republic banned the Jesuits, which deeply offended many of the Nationalists. Nothwithstanding these religious matters, the Basque nationalists, who nearly all sided with the Republic, were, for the most part, practicing Catholics. John Paul II has recently canonized several of these martyrs of the Spanish Civil War, murdered for being priests or nuns. The rebellion was opposed by the government (with the troops that remained loyal), as well as by Socialist, Communist and anarchist groups. The European powers such as Britain and France were officially neutral but still imposed an arms embargo on Spain, and actively discouraged the anti-fascist participation of their citizens. Both fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini and Nazi Germany violated the embargo and sent troops (Corpo Truppe Volontari and Legión Cóndor) and weapons to support Franco. In addition, there were a few volunteer troops from other nations who fought with the Nationalists, such as Eoin O'Duffy of Ireland. The Republicans received limited support from the Soviet Union as well as from volunteers from many countries, collectively known as the International Brigades. American volunteers formed the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and Canadians formed the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (the "Mac-Paps"). Among the more famous foreigners participating in the efforts against the fascists were Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell, who went on to write about his experiences in Homage to Catalonia. Hemingway's novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was inspired by his experiences in Spain. Norman Bethune used the opportunity to develop the special skills of battlefield medicine. As a casual visitor Errol Flynn used a fake report of his death at the battlefront to promote his movies. However, though the Nationalists were receiving overt aid in the form of arms and troops from Germany and Italy, the Republicans received no aid from any major world powers (e.g. Britain or France or the United States). Many of these powers were still practising a policy of appeasement towards Fascist regimes, or they viewed social revolutionary elements within the anti-fascist forces with distaste, or they believed that the Republicans were Communists. Germany used the war as a testing ground for faster tanks and aircraft that were just becoming available at the time. The Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter and Junkers Ju 52 transport/bomber were both used in the Spanish Civil War. In addition, the Soviet I-15 fighter and I-16 fighters were used. The Spanish Civil War was also an example of total war, where the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by the Legión Cóndor, as depicted by Pablo Picasso in Guernica, foreshadowed episodes of World War II such as the bombing campaign on Britain by the Nazis and the bombing of Dresden by the Allies.

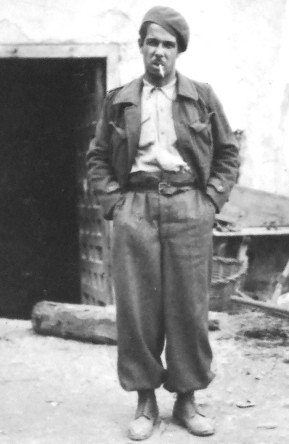

Sheffield and Spanish Civil War. Joe Albaya, Sheffield International Brigade volunteer from Woodseats, Sheffield, 1930s. Sheffield men fought alongside the Spanish people in their struggle for democracy during the Spanish Civil War (1936 - 1939). Many men and women in Sheffield worked in support of the cause. 2011 marks the 75th anniversary of the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and a series of events are being held to commemorate the occasion.

Spanish Civil War.image from our Spanish Civil War in Barcelona walk

Spanish Civil War. image from our Spanish Civil War in Barcelona walk

Spanish Civil War image from our Spanish Civil War in Barcelona walk

|

Following an aerial attack on Madrid from 16 rebel planes from Tetuan, Spanish Morocco, relatives of those trapped in ruined houses appeal for news of their loved ones, Jan. 8, 1937. The faces of these women reflect the horror non-combatants are suffering in the civil struggle. (AP Photo) #

A fascist machine gun squad, backed up by expert riflemen, hold a position along the rugged Huesca front in northern Spain, Dec. 30, 1936. (AP Photo) #

Solemnly promising the nation his utmost effort to keep the country neutral, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt is shown as he addressed the nation by radio from the White House in Washington, Sept. 3, 1939. In the years leading up to the war, the U.S. Congress passed several Neutrality Acts, pledging to stay (officially) out of the conflict. (AP Photo) # Riette Kahn is shown at the wheel of an ambulance donated by the American movie industry to the Spanish government in Los Angeles, California, on Sept. 18, 1937. The Hollywood Caravan to Spain will first tour the U.S. to raise funds to "help the defenders of Spanish democracy" in the Spanish Civil War. (AP Photo) #

Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Joris Ivens, Ernest Hemingway, and Ludwig Renn (Spanish Civil War, 1937) Nationalrevolutionärer Krieg des spanischen Volkes vom 18.7.1936 bis 2.4.1939/ Internationale Brigaden Während des spanischen Freiheitskampfes weilten Joris Ivens, holländischer Filmregisseur (links) und Ernest Hemingway, nordamerikanischer Schriftsteller (Mitte) bei den Internationalen Brigaden. Ludwig Renn, Chef des Stabes der XI.Internationalen Brigaden, Kommandeur des Thälmann-Bataillons (rechts).

Ernest Hemingway, Milan 1918.Ernest Hemingway, American Red Cross volunteer. Portrait by Ermeni Studios, Milan, Italy. (Credit: Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.) |

|

|

|  |

No comments:

Post a Comment