The west should sink those illegal fishing of China as it avoids Kinetic warfare but indulge with media threats

Western history can be seen as having several inflection points: one was 1492, the advent of the “Columbian Era”. The Columbian era is the era of sea-faring, sea-power-based Western colonial and imperial empires. The demise of the Columbian era, was foreshadowed by an Oxford geographer in 1904 who put forth what is now known as the “Heartland Theory”. In a nutshell, it is a land-based theory of power that predicts the end of sea-based powers: “Who rules East Europe (Eurasia) commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.” It also concluded, “Were the Chinese…to…conquer its territory [of the Russian Empire], they might constitute the yellow peril to the world’s freedom.” This maxim and the anxiety it provoked was red-lined in Brezinski’s “Grand Chess game”: “No Eurasian challenger should emerge that can dominate Eurasia and thus also challenge U.S. global pre-eminence.”

In 1992, Marshall’s protégé, Paul Wolfowitz formulated the above strands into a formal doctrine, in the above mentioned DPG (Defense Planning guidance) document:

“Our first objective is to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival… that poses a threat on the order of that posed formerly by the Soviet Union…to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region to generate global power…The U.S. must… protect a new order that [convinces] potential competitors that they need not aspire to a greater role or pursue a more aggressive posture to protect their legitimate interests. In non-defense areas, we must… discourage them from challenging our leadership or seeking to overturn the established political and economic order. We must maintain the mechanism for deterring potential competitors from even aspiring to a larger regional or global role.”

This can be better understood by looking at a map:

This is a map of the world, drawn from a topologist’s eye. It shows relationships, not distances or area. From this map you can note the following things:

+ China has more borders than any other country in the world. This also gives it the possibility of connecting with more countries than any other.

+ Blue lines/corridors are oceans: The top two thirds is the “world island” or “pivot state”–it contains most of the world’s population, resources, and wealth, and it can be connected as a single entity through overland routes or short ocean hops.

+ The bottom is the Americas. It is topologically isolated from the world island. As sea lane control becomes less important, it will also lose prominence and relative power if the world island unifies. It’s clear that that unifying power will probably arise in China, whose overland paths using high-speed rail, roads, pipelines, and ports can be easily built and connected, in a “new silk road”.

+ The US needs to fracture the world island to maintain its global power. If you color in the places where China is encircled, or where the US is waging war/fracturing societies/creating chaos, this is exactly where the fault lines of the global conflict are, and reveal what US strategy is.

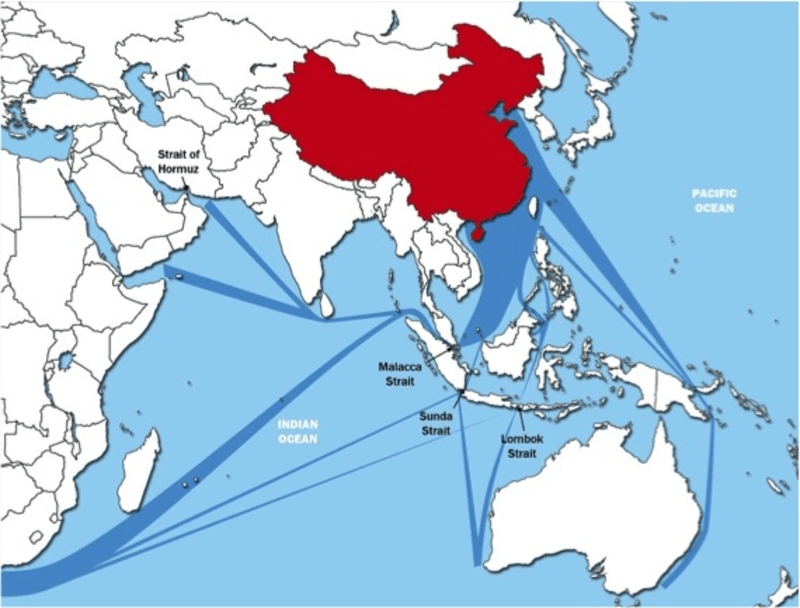

Here is a second map:

Image: CSBA: Shipping Lanes through the South China Sea.

The US has actually surrounded China with 400 military bases, bristling with strategic and tactical weaponry. It also has war-gamed out China’s key vulnerability: the chokepoint of the South China Sea. War in the South China Sea would disrupt $5.3 Trillion of China’s external trade and 77% of China’s oil imports[5]. In this scenario, the US does not have to win a shooting war with China in the South China Sea. The war just has to happen, and the disruption to trade could crash China’s economy. The map shows the shipping lanes that would be disrupted.

China’s first response to the US pivot and encirclement, especially in the South China Sea–its key chokepoint–was to build defensive military facilities along some of the islands, to deter US incursion and to raise the cost of interference. Its other response, much more ambitious, was the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI), which constitutes a long overland escape from the encirclement, similar to its “long march” during its encirclement by the fascist KMT. The BRI travels through SE Asia, then overland through Central Asia, to the Mediterranean, and then Europe and Africa. In particular:

+ CMEC (China-Myanmar Economic Corridor) travels through Rakhine State and exits to the Indian Ocean at Kyaukphyu port (bypassing the Strait of Malacca).

+ CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) to Gwadar port transits directly to the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf.

+ Xinjiang is the key overland route for BRI to exit China to Central Asia, with Iran also a key node.

+ Djibouti at the horn of Africa is the entry node to Africa (the Sahel, and the South)

BRI as it does this, becomes the physical realization of Mackinder’s “heartland” in Eurasia—the pivot state connecting the “world island” into a single economic bloc, and raising China to the status of the key regional power, exactly what Brezinski and Wolfowitz, sought to prevent.

Image: Mercator Institute for China Studies: Belt and Road Initiative.

Mindful of this development, and aware of the rapidly ticking biological clock on US power, the US is currently rapidly escalating hostilities in the SCS, most recently with war games, U2 incursions, belligerent passages of aircraft carriers, guided missile destroyers, submarines; China’s response has been to launch “carrier killer” missiles into the region.

In December 2018, Rear Admiral Lou Yuan of the PLA Navy said, ‘What the United States fears the most is taking casualties,’ and suggested that sinking two US aircraft carriers would be sufficient to expel the US from the South and East China seas. ‘We’ll see how frightened America is.’

The authors say that using this concept of ‘offensive deterrence’ by conducting strikes that kill Americans or Australians would not have the deterrent effect the PRC seeks or expects ‘and the risks of escalation from such a deterrent effort are extremely high’.

So, they say, planners must take this into account both when seeking to deter China as well as when thinking through what actions it might take or how it might react to our actions.

In examining how China might be deterred from actions inimical to international goals and standards, the report contains various definitions of what deterrence actually is. One is that of strategist Thomas Schelling, described as the contemporary father of coercion theory: ‘To be coercive, violence has to be anticipated. And it has to be avoidable by accommodation. The power to hurt is bargaining power. To exploit it is diplomacy—vicious diplomacy, but diplomacy.’

Zhao Xijun of the PRC’s National Defense University defines ‘offensive deterrence’ in his book Coercive warfare: a comprehensive discussion on missile deterrence as ‘a military deterrence that mainly aims at attacking’ and writes that ‘the characteristic of offensive deterrence is to use “pre-emptive strike” to deter the other side’. Zhao also states that this concept is ‘“using war to stop war” by [using] small war to constrain large war’.

The authors compare the current situation to the way the US and the Soviet Union related to each other during the Cold War. Apart from contact at organisations such as the United Nations, the two sides had little interaction, little trade, little commerce and relatively little overlap in their geographical spheres of influence.

‘There was tension and conflict on the margins with clear escalatory potential, but the two sides managed to avoid direct or large-scale confrontations, albeit narrowly at times. That was in large part because the two sides developed a shared basic understanding of the world.’

Everyone in the military and the broader defence and security establishment knew something about the Soviets and their military. People studied what the Soviets thought, how they spoke and the actions that they took, down to the smallest details.

Each side developed a solid basis for understanding the signals the other side was sending, and typically sent clear signals of its own.

The authors say that that is not the case today.

‘The CCP’s understanding of the world, and thus its approach to it, is significantly different from Western views. It’s neither right nor wrong, just a different perspective, and one that isn’t common in Western liberal democracies; nor is it commonly taught in Western education systems, or indeed even in professional military education.’

They say that Australian and US partners and allies such as Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan have a historical appreciation and can help contribute to a better understanding of historical concepts. But, since 2001, the US and many of its partners have been focused on fighting terrorist groups and managing the conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and the broader Middle East.

Only during the latter part of the Trump administration did the US truly focus the whole of government on addressing the competition with China, bringing in Congress as well as the military, the State Department, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States and others.

While it takes years to build a deep and wide group of specialists in any field, the authors say, it stands out that the US Air Force has the same number of foreign area officer places for Chinese specialists as it does for Portuguese speakers.

They warn that if the US and its allies and partners hope to avoid conflict with China, they must build a deeper shared understanding of how the CCP and the PRC see the world. That will require sustained effort over several years and involve a deep partnership with partners and allies who have vital knowledge and expertise.

They also urge planners not to ‘mirror ourselves onto our analysis of PRC thinking and action’.

They say that: ‘With sustained effort, we can do better at understanding Chinese thought and concepts and the twists that CCP ideology gives them. In that way, we can maximise our opportunities to ensure that our strategic goals are met and our interests are protected.’

The Americans counter-attacked the next day with fresh troops and gunboats. They pushed the Filipinos into Tondo (LEFT, dead Filipinos on a Tondo street). At the tramway station, Paco Roman's men resisted until late in the morning. Others were able to hold a blockhouse but had to withdraw for lack of ammunition.

The Americans counter-attacked the next day with fresh troops and gunboats. They pushed the Filipinos into Tondo (LEFT, dead Filipinos on a Tondo street). At the tramway station, Paco Roman's men resisted until late in the morning. Others were able to hold a blockhouse but had to withdraw for lack of ammunition.

Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton (LEFT) led five American regiments against Filipino forces entrenched in the area surrounding the church at Guadalupe, San Pedro de Macati (now Makati City).

Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton (LEFT) led five American regiments against Filipino forces entrenched in the area surrounding the church at Guadalupe, San Pedro de Macati (now Makati City).