|  Guadalcanal-Tulagi Operation, August 1942

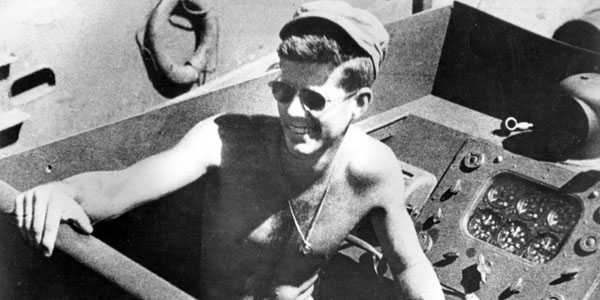

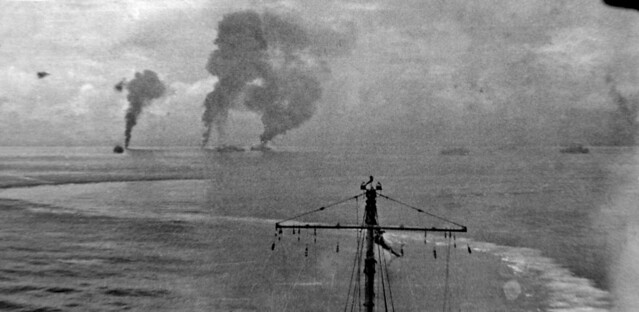

Makambo Island, inside Tulagi harbor just north of Tulagi Island, under bombardment by Allied ships and U.S. carrier aircraft on 7 August 1942, the day U.S. Marines landed on Tulagi. A pattern of four shells has just landed in the water nearby and fires are burning ashore. Despite having a bad back, Kennedy was able to join the U.S. Navy through the help of Captain Alan Kirk, the Director, Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) who had been the Naval Attache in London when Joseph Kennedy was the Ambassador. In October 1941, Kennedy was appointed an Ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve and joined the staff of the Office of Naval Intelligence. The office, for which Kennedy worked, prepared intelligence bulletins and briefing information for the Secretary of the Navy and other top officials. On 15 January 1942, he was assigned to an ONI field office the Sixth Naval District in Charleston, South Carolina. After spending most of April and May at Naval Hospitals at Charleston and at Chelsea, Massachusetts, Kennedy attended Naval Reserve Officers Training School at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, from 27 July through 27 September. After completing this training, Kennedy entered the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Training Center, Melville, Rhode Island. On 10 October, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant, Junior Grade. Upon completing his training 2 December, he was ordered to the training squadron, Motor Torpedo  Squadron FOUR, for duty as the Commanding Officer of a motor torpedo boat, PT 101, a 78- foot Higgins boat. In January 1943, PT 101 with four other boats was ordered to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron FOURTEEN, which was assigned to Panama. Seeking combat duty, Kennedy transferred on 23 February as a replacement officer to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron TWO, which was based at Tulagi Island in the Solomons. Traveling to the Pacific on USS Rochambeau, Kennedy arrived at Tulagi on 14 April and took command of PT 109 on 23 April 1943. On 30 May, several PT boats, including PT 109 were ordered to the Russell Islands, in preparation for the invasion of New Georgia. After the invasion of Rendova, PT 109 moved to Lumbari. From that base PT boats conducted nightly operations to interdict the heavy Japanese barge traffic resupplying the Japanese garrisons in New Georgia and to patrol the Ferguson and Blackett Straits near the islands of Kolumbangara, Gizo, and Vella-Lavella in order to sight and to give warning when the Japanese Tokyo Express warships came into the straits to assault U.S. forces in the New Georgia-Rendova area.

PT 109 commanded by Kennedy with executive officer, Ensign Leonard Jay Thom, and ten enlisted men was one of the fifteen boats sent out on patrol on the night of 1-2 August 1943 to intercept Japanese warships in the straits. A friend of Kennedy, Ensign George H. R. Ross, whose ship was damaged, joined Kennedy's crew that night. The PT boat was creeping along to keep the wake and noise to a minimum in order to avoid detection. Around 0200 with Kennedy at the helm, the Japanese destroyer Amagiri traveling at 40 knots cut PT 109 in two in ten seconds. Although the Japanese destroyer had not realized that their ship had struck an enemy vessel, the damage to PT 109 was severe. At the impact, Kennedy was thrown into the cockpit where he landed on his bad back. As Amagiri steamed away, its wake doused the flames on the floating section of PT 109 to which five Americans clung: Kennedy, Thom, and three enlisted men, S1/c Raymond Albert, RM2/c John E. Maguire and QM3/c Edman Edgar Mauer. Kennedy yelled out for others in the water and heard the replies of Ross and five members of the crew, two of which were injured. GM3/c Charles A. Harris had a hurt leg and MoMM1/c Patrick Henry McMahon, the engineer was badly burned. Kennedy swam to these men as Ross and Thom helped the others, MoMM2/c William Johnston, TM2/c Ray L. Starkey, and MoMM1/c Gerald E. Zinser to the remnant of PT 109. Although they were only one hundred yards from the floating piece, in the dark it took Kennedy three hours to tow McMahon and help Harris back to the PT hulk. Unfortunately, TM2/c Andrew Jackson Kirksey and MoMM2/c Harold W. Marney were killed in the collision with Amagiri. PT 109 commanded by Kennedy with executive officer, Ensign Leonard Jay Thom, and ten enlisted men was one of the fifteen boats sent out on patrol on the night of 1-2 August 1943 to intercept Japanese warships in the straits. A friend of Kennedy, Ensign George H. R. Ross, whose ship was damaged, joined Kennedy's crew that night. The PT boat was creeping along to keep the wake and noise to a minimum in order to avoid detection. Around 0200 with Kennedy at the helm, the Japanese destroyer Amagiri traveling at 40 knots cut PT 109 in two in ten seconds. Although the Japanese destroyer had not realized that their ship had struck an enemy vessel, the damage to PT 109 was severe. At the impact, Kennedy was thrown into the cockpit where he landed on his bad back. As Amagiri steamed away, its wake doused the flames on the floating section of PT 109 to which five Americans clung: Kennedy, Thom, and three enlisted men, S1/c Raymond Albert, RM2/c John E. Maguire and QM3/c Edman Edgar Mauer. Kennedy yelled out for others in the water and heard the replies of Ross and five members of the crew, two of which were injured. GM3/c Charles A. Harris had a hurt leg and MoMM1/c Patrick Henry McMahon, the engineer was badly burned. Kennedy swam to these men as Ross and Thom helped the others, MoMM2/c William Johnston, TM2/c Ray L. Starkey, and MoMM1/c Gerald E. Zinser to the remnant of PT 109. Although they were only one hundred yards from the floating piece, in the dark it took Kennedy three hours to tow McMahon and help Harris back to the PT hulk. Unfortunately, TM2/c Andrew Jackson Kirksey and MoMM2/c Harold W. Marney were killed in the collision with Amagiri.

Because the remnant was listing badly and starting to swamp, Kennedy decided to swim for a small island barely visible (actually three miles) to the southeast. Five hours later, all eleven survivors had made it to the island after having spent a total of fifteen hours in the water. Kennedy had given McMahon a life-jacket and had towed him all three miles with the strap of the device in his teeth. After finding no food or water on the island, Kennedy concluded that he should swim the route the PT boats took through Ferguson Passage in hopes of sighting another ship. After Kennedy had no luck, Ross also made an attempt, but saw no one and returned to the island. Ross and Kennedy had spotted another slightly larger island with coconuts to eat and all the men swam there with Kennedy again towing McMahon. Now at their fourth day, Kennedy and Ross made it to Nauru Island and found several natives. Kennedy cut a message on a coconut that read "11 alive native knows posit & reef Nauru Island Kennedy." He purportedly handed the coconut to one of the natives and said, "Rendova, Rendova!," indicating that the coconut should be taken to the PT base on Rendova. Kennedy and Ross again attempted to look for boats that night with no luck. The next morning the natives returned with food and supplies, as well as a letter from the coastwatcher commander of the New Zealand camp, Lieutenant Arthur Reginald Evans. The message indicated that the natives should return with the American commander, and Kennedy complied immediately. He was greeted warmly and then taken to meet PT 157 which returned to the island and finally rescued the survivors on 8 August. Kennedy was later awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his heroics in the rescue of the crew of PT 109, as well as the Purple Heart Medal for injuries sustained in the accident on the night of 1 August 1943. An official account of the entire incident was written by intelligence officers in August 1943 and subsequently declassified in 1959. As President, Kennedy met once again with his rescuers and was toasted by members of the Japanese destroyer crew. In September, Kennedy went to Tulagi and accepted the command of PT 59 which was scheduled to be converted to a gunboat. In October 1943, Kennedy was promoted to Lieutenant and continued to command the motor torpedo boat when the squadron moved to Vella Lavella until a doctor directed him to leave PT 59 on 18 November. Kennedy left the Solomons on 21 December and returned to the U.S. in early January 1944. On 15 February, Kennedy reported to the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Training Center, Melville, Rhode Island. Due to the reinjury of his back during the sinking of PT 109, Kennedy entered a hospital for treatment. In March, Kennedy went to the Submarine Chaser Training Center, Miami, Florida. In May while still assigned to the Center, Kennedy entered the Naval Hospital, Chelsea, Massachusetts, for further treatment of his back injury. At the Hospital in June, he received his Navy and Marine Corps Medals. Under treatment as an outpatient, Kennedy was ordered detached from the Miami Center on 30 October 1944. Subsequently, Kennedy was released from all active duty and finally retired from the U.S. Naval Reserve on physical Amagiri (Destroyer, 1930-1944)  A A

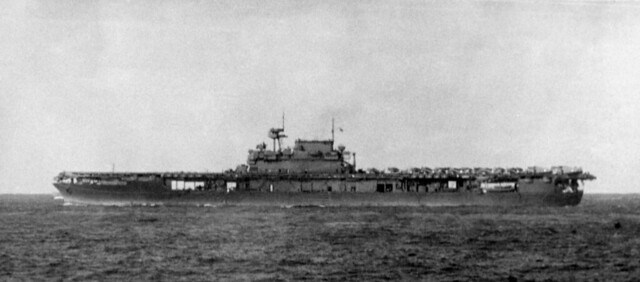

Amagiri, a 1750-ton Fubuki class destroyer, was built at Tokyo, Japan. She was completed in November 1930 and spent the next decade taking part in combat exercises and, during the later 1930s, in operations connected with the Sino-Japanese War. When Japan began the Pacific War on 8 December 1942, Amagiri covered landings on the coast of Thailand. Later involved with the campaign to conquer Malaya and Singapore, she engaged two British destroyers off the Malay coast on the night of 27 January 1942. She also supported the invasion of western Java in February and served with Admiral Yamamoto's force in the Battle of Midway Amagiri participated in the 14-15 October and 14 November bombardment missions during the Guadalcanal Campaign, and helped escort the last major Japanese convoy to that island, on 15 November 1942. Employed as a high-speed transport during the Central Solomons Campaign, she participated in the Battle of Kula Gulf on the night of 5-6 July 1943. While on another reinforcement run to Vila on 2 August, Amagiri rammed and sank the U.S. motor torpedo boat PT-109 and engaged other PT boats in Blackett Strait, south of Kolombangara. Later in the year, she was at Rabaul during the U.S. carrier air raids on 5 and 8 November and carried troops to Bougainville on 6-7 November. Another reinforcement mission to Bougainville, on 24-25 November 1943, resulted in the Battle of Cape Saint George, in which Amagiri escaped pursuing U.S. destroyers led by Captain Arleigh Burke. She was sunk by a mine near Borneo on 23 April 1944.  Kinugawa Maru (Japanese cargo ship)

Beached and sunk on the Guadalcanal shore, November 1943.

She had been sunk by U.S. aircraft on 15 November 1942, while attempting to deliver men and supplies to Japanese forces holding the northern part of the island.

Savo Island is in the distance.

In the six months between August 1942 and February 1943, the United States and its Pacific Allies fought a brutally hard air-sea-land campaign against the Japanese for possession of the previously-obscure island of Guadalcanal. The Allies' first major offensive action of the Pacific War, the contest began as a risky enterprise since Japan still maintained a significant naval superiority in the Pacific ocean. Nevertheless, the U.S. First Marine Division landed on 7 August 1942 to seize a nearly-complete airfield at Guadalcanal's Lunga Point and an anchorage at nearby Tulagi, bounding a picturesque body of water that would soon be named "Iron Bottom Sound". Action ashore went well, and Japan's initial aerial response was costly and unproductive. However, only two days after the landings, the U.S. and Australian navies were handed a serious defeat in the Battle of Savo Island. A lengthy struggle followed, with its focus the Lunga Point airfield, renamed Henderson Field. Though regularly bombed and shelled by the enemy, Henderson Field's planes were still able to fly, ensuring that Japanese efforts to build and maintain ground forces on Guadalcanal were prohibitively expensive. Ashore, there was hard fighting in a miserable climate, with U.S. Marines and Soldiers, aided by local people and a few colonial authorities, demonstrating the fatal weaknesses of Japanese ground combat doctrine when confronted by determined and well-trained opponents who possessed superior firepower. At sea, the campaign featured two major battles between aircraft carriers that were more costly to the Americans than to the Japanese, and many submarine and air-sea actions that gave the Allies an advantage. Inside and just outside Iron Bottom Sound, five significant surface battles and several skirmishes convincingly proved just how superior Japan's navy then was in night gunfire and torpedo combat. With all this, the campaign's outcome was very much in doubt for nearly four months and was not certain until the Japanese completed a stealthy evacuation of their surviving ground troops in the early hours of 8 February 1943. Guadalcanal was expensive for both sides, though much more so for Japan's soldiers than for U.S. ground forces. The opponents suffered high losses in aircraft and ships, but those of the United States were soon replaced, while those of Japan were not. Strategically, this campaign built a strong foundation on the footing laid a few months earlier in the Battle of Midway, which had brought Japan's Pacific offensive to an abrupt halt. At Guadalcanal, the Japanese were harshly shoved into a long and costly retreat, one that continued virtually unchecked until their August 1945 capitulation.

Photo #: 80-G-17066

Guadalcanal-Tulagi Operation, August 1942

Japanese Navy Type 1 land attack planes (later nicknamed "Betty") fly low through anti-aircraft gunfire during a torpedo attack on U.S. Navy ships maneuvering between Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the morning of 8 August 1942.

Note that these planes are being flown without bomb-bay doors.

Photo #: NH 97766

Guadalcanal-Tulagi Operation, August 1942

Japanese Navy Type 1 land attack planes ("Betty") make a torpedo attack on the Tulagi invasion force, 8 August 1942. The burning ship in the center distance is probably USS George F. Elliott (AP-13), which was hit by a crashing Japanese aircraft during this attack.

The original photograph came from the illustrations package for Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison "History of United States Naval Operations in World War II", volume IV (originally published opposite page 293).

Photo #: NH 69117

Guadalcanal - Tulagi Operation, August 1942

A Japanese torpedo plane attack on U.S. transports between Guadalcanal and Tulagi, 8 August 1942.

Several G4M1 bombers are visible, flying low through anti-aircraft shell bursts near the destroyer in the center.

Photo #: NH 97751

Guadalcanal-Tulagi Operation, August 1942

Ships maneuvering during the Japanese torpedo plane attack on the Tulagi invasion force, 8 August 1942. Several Japanese Navy Type 1 land attack planes ("Betty") are faintly visible at left, center and right, among the anti-aircraft shell bursts. Destroyer in the foreground appears to be USS Bagley (DD-386) or USS Helm (DD-388). A New Orleans class heavy cruiser is in the left distance, with a large splash beside it. Column of smoke in the left center is probably from a crashed plane.

The original photograph came from Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison's World War II history project working files.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Online Image: 68KB; 740 x 560 pixels

Photo #: NH 97752

Guadalcanal-Tulagi Operation, August 1942

Ships maneuvering during the Japanese torpedo plane attack on the Tulagi invasion force, 8 August 1942. Several Japanese Navy Type 1 land attack planes ("Betty") are faintly visible in the center and at right. The ship in the left center appears to be USS San Juan (CL-54). Other ships present include two destroyers, a fast transport and a heavy cruiser, with the latter very distant at the right.

The original photograph came from Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison's World War II history project working files.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Online Image: 68KB; 740 x 560 pixels PT-109 Motor Torpedo Boat 109 (PT-109) was laid down 4 March 1942 by the Elco Works Naval Division of the Electric Boat Company in Bayonne, New Jersey. The seventh 40-ton Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) built there, she was launched on 20 June, delivered to the Navy on 10 July 1942, and fitted out in the New York Naval Shipyard at Brooklyn. PT-109 joined MTB Squadron FIVE and shifted to Panama, replacing the first eight PT boats that sailed on transports for the south Pacific in early September. Six of the Elco boats, PTs 109 through 114, were then transferred to MTB Squadron TWO on 26 October 1942 and prepared for deployment to the Solomon Islands. The boats were loaded on cargo ships and sailed west, arriving at Sesapi, Tulagi harbor, Nggela Islands, at the end of November. There, the Elco boats joined the earlier boats--which had established the MTB base at Sesapi in October--to form Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla ONE, under Commander Allen P. Calvert.  The sound between the Nggela Islands and Guadalcanal, called "Iron Bottom Sound" for the number of warships sunk there, was geographically favorable for PT operations. The two western entrances, one between Cape Esperance and Savo Island to the south; and the other, between Savo Island and Sandfly Passage to the north, were relatively narrow. Finally, the western tip of Guadalcanal was less than thirty-five miles across sheltered water from the PT base at Sesapi. The sound between the Nggela Islands and Guadalcanal, called "Iron Bottom Sound" for the number of warships sunk there, was geographically favorable for PT operations. The two western entrances, one between Cape Esperance and Savo Island to the south; and the other, between Savo Island and Sandfly Passage to the north, were relatively narrow. Finally, the western tip of Guadalcanal was less than thirty-five miles across sheltered water from the PT base at Sesapi.

Starting the night of 13-14 October, when four boats attacked a Japanese force bombarding Henderson Field, it became regular practice to send the MTBs out on patrol when Japanese warships were reported heading down the "slot"--the broad passage between New Georgia and Santa Isabel. These reinforcement missions--delivering men and supplies to the Japanese-held shore of Guadalcanal--were called the "Tokyo Express." When those forces were spotted by plane or coast watcher, the torpedo boats put out from Tulagi and stationed pickets in the channels around Savo Island. Other motor torpedo boats waited inside "Iron Bottom Sound," ready to move toward either passage when enemy ships were spotted. The first action for PT-109, then commanded by Lt. Rollins E. Westholm, took place on the night of 7-8 December 1942, after reconnaissance planes reported eight Japanese destroyers moving down the "slot." Eight PTs split into three groups to meet this opposing force, with patrols off Kokumbona, another off Cape Esperance, and a four-boat division lay to [came to a stationary position] near Savo Island to act as a striking force. After initial contact took place off Cape Esperance, the striking group of four boats closed and unleashed a torpedo attack. In the ensuing running gun battle, the PTs weaved around the destroyers in a confused melee. Although PT-59 was hit by shellfire, and suffered minor damage, the Japanese withdrew, racing north with uncertain damage and without delivering their reinforcements. Four days later, five patrolling PT boats encountered eleven Japanese destroyers northwest of Savo Island. In the melee, the MTBs managed to torpedo and sink destroyer Terutsuki at the cost of PT-44, sunk by two destroyers off Savo Island. In early January 1943, PT-109 encountered the Japanese several more times as she and her sister boats continued intercepting "Tokyo Express" supply runs. On the night of 2-3 January, she had two bombs from an enemy plane explode off her port beam and, after firing torpedoes at an enemy destroyer, a Japanese patrol plane strafed her wake east of Savo Island. In the early morning darkness of 9 January, the PT boat closed [approached] the beach on Guadalcanal to destroy enemy stores by strafing a supply depot with .50 caliber and 20-mm guns. Then, on the night of 11-12 January, PT-109 joined eight other MTBs to attack eight Japanese destroyers off Cape Esperance. In the ensuing battle, PT-112 was sunk and PT-43 damaged, though not before a torpedo hit seriously damaged Japanese destroyer Hatsukaze. On night patrol on 14-15 January 1943, PT-109 unsuccessfully searched northwest of Savo for signs of nine expected Japanese destroyers. At one point, a patrolling plane dropped a depth charge about 150 yards off the port quarter. Before dawn, she closed Cape Esperance looking for an opportunity to attack enemy troops and stores. At daylight, however, enemy shore batteries caught her in range and punched three holes in her hull. She then made an unsuccessful attempt to pull PT-72 off a reef southwest of Florida Island before returning to base. During the night of 1-2 February 1943, twenty Japanese destroyers steamed down the slot as part of Operation "KE," the evacuation of their remaining troops from Guadalcanal. Although attacked by two waves of fighters and bombers from Henderson Field at dusk, only one destroyer was damaged. The rest closed Cape Esperance, covered by half a dozen patrol planes. The Japanese were spotted by eleven PT boats in positions around Savo Island, but heavy defensive fire drove off the attacking PT boats. Accurate gunfire from Kawakaze sank PT-111 and PT-37, while a Japanese seaplane destroyed PT-123. During the battle, both PT-115 and PT-38 beached themselves on the western side of Savo Island and were pulled off by PT-109. This was the most violent action the PTs participated in off Guadalcanal, and it was their last, as the Japanese completed their evacuation of that island on 7-8 February. Over the next few months, while the MTB flotilla regrouped on Tulagi, the Japanese devoted most of their efforts to strengthening their garrisons in the upper Solomons. There were few offensive operations by either side, a respite sorely needed by PT-109 and her sister boats. The flotilla was short on manpower, with barely enough men to man the motor torpedo boats, let alone repair those damaged in combat and maintain adequate base facilities. Indeed, the crews were exhausted and easy prey to malaria, dengue fever and other tropical diseases. During this trying period, Lt. Westholm left PT-109 to become operations officer for the flotilla, leaving Ensign Bryant L. Larson in command of the boat. On 21 February, the MTBs escorted transports for the invasion of the Russell Islands, with PT-109 personally delivering Col. E. J. Farrel and his staff to the beach in Renard Sound. After the transports landed the remaining Marine and Army troops, the PTs began nightly offshore security patrols to protect the beach head. Additional patrols covered the familiar channels off Savo Island in case the Japanese returned to the Solomons. These operations became more difficult on 5 March, when a single plane dropped four bombs on Senapi, destroying the operations office and riddling the hull of PT-118. Then, on 7 April, the last major Japanese air strike in the Solomons managed to sink three Allied ships in Tulagi harbor and damage two others, temporarily disrupting MTB base operations. In between regular security patrols, PT-109 underwent several short maintenance periods, which included the installation of a surface search radar set. As radar sets were not issued with this class of PT-boats, the device was undoubtedly a "scrounged" item and it is unclear how long it lasted. Ensign Larson left the boat on 20 April 1943 and Ensign Leonard J. Thom, USNR, the executive officer, took charge until relieved by Lieutenant (jg) John Fitzgerald Kennedy, USNR, on the 24th. Starting in late April, the motor torpedo boat increasingly conducted patrols in the Russell Islands area and on 16 June, PT-109 shifted with other boats to a "bush" berth on Rendova Island in support of these forward operations. On 1 August, an air strike by 18 Japanese bombers struck this temporary base, wrecking PT-117 and sinking PT-164. Two torpedoes were blown off the latter boat and ran erratically around the bay until they fetched upon [ran ashore on] the beach without exploding. Intelligence reports indicated five enemy destroyers were scheduled to run that night from Bougainville Island through Blackett Strait to Vila, on the southern tip of Kolombangara Island. Despite the loss of two boats, the flotilla sent out fifteen motor torpedo boats out in four sections to meet the Japanese destroyers. Lieutenant Brantingham in PT-159 made radar contact at midnight with ships approaching from the north, close to Kolombangara. Soon after this he sighted what he believed to be large landing craft and closed range for a strafing run only to run into heavy shellfire that revealed the "landing craft" to be destroyers. He got off four torpedoes, and PT-157 launched two as well, before the two boats withdrew. Lieutenant Kennedy in PT-109 patrolled without incident until gunfire and searchlights were seen in the direction of the southern shore of Kolombangara. The location was undetermined, however, and the boat rendezvoused with PT-162 to determine the source of firing. PT-109 then intercepted a terse radio message [probably from PT-159] "I am being chased through Ferguson Passage! Have fired fish." At this time, PT-169 came alongside and reported an engine out of order. She lay to with PT-109 and PT-162 to await developments while instructions were requested from base. Orders were received to resume normal patrol station, and PT-162 being uncertain as to its position, requested Lieutenant Kennedy to lead the way back to patrol station. Lieutenant Kennedy started his patrol on one engine ahead at idling speed. The three boats were due east of Gizo Island and headed south with PT-109 leading a right echelon formation. Unknown to them, the Japanese destroyer Amagiri was returning north after completing a supply mission to Kolobangara and had spotted the torpedo boats at a range of about 1,000 yards. Rather than open fire--and give away their position--the destroyer captain, Lieutenant Comander Kohei Hanami, turned to intercept and closed in the darkness at 30-knots. Initially spotted by PT-109 at 200 to 300 yards, Kennedy ordered the boat turned to starboard, preparatory to firing torpedoes. The turn was too slow, however, and the destroyer rammed, neither slowing or firing her guns as she split the boat apart. While the Japanese destroyer was slightly damaged in the collision, smashing in part of her bow and bending her screws, the warship still made 24-knots on the run home to Rabaul and arrived safely the following morning. Meanwhile, the crew of PT-109 were thrown in the water as the Japanese destroyer knifed through their boat. Fire ignited spilled gasoline on the water some twenty yards around the wreckage, driving the crew in all directions. It quickly became clear that the forward half of the boat was still floating after the flames died down and Lieutenant Kennedy, Ensign Thom, Ensign George Ross, QM3 [Quarter Master Third Class] Edman Mauer, RM2 [Radioman Second Class] John Maguire and S1 [Seaman First Class] Raymond Albert all crawled back on board the hull. Shouting soon revealed three men were in the water some 100 yards to the southwest, while two others were an equal distance to the southeast. These were GM3 Charles Harris, MoMM2 [Motor Machinist Mate Second Class] William Johnston, MoMM1 [Motor Machinist Mate First Class] Patrick McMahon, TM2 [Torpedoman Second Class] Ray Starkey and MoMM1 [Motor Machinist Mate First Class] Gerald Zinser. Lieutenant Kennedy swam to the group of three where he found one man helpless because of serious burns and another struggling to stay afloat owing to a water-logged kapok life jacket. Trading his life belt to the latter sailor, he towed the injured man back to the wreckage of PT-109. Returning to the scene, he helped tow the exhausted crew member back to the boat. Meanwhile Ensigns Thom and Ross towed the other two survivors back to the floating section. Two sailors, TM2 Andrew Kirksey and MoMM2 Harold Marney, were never seen and presumed killed in the collision with Amagiri. Daylight on 2 August found all eleven survivors clinging to the wreckage of PT-109 about four miles north and slightly east of Gizo anchorage. When it became obvious the boat remnants would sink, Kennedy decided to abandon ship to a small island some four miles southeast of Gizo, hoping to avoid any Japanese garrisons that way. At 1400, the crew pushed off for land, towing the badly burned engineer and two non-swimmers on a float rigged from a wooden post which had been a part of the 37mm gun mount. Arriving on shore, the group took cover and set up a temporary camp. That night, Kennedy grabbed a salvaged battle lantern, donned a lifejacket, and swam to a small island a half-mile to the southeast, then along the reef stretching into Ferguson Passage where he tried unsuccessfully to intercept patrolling motor torpedo boats. Returning in the morning, he turned the lantern over to Ensign Ross who swam the same route into Ferguson Passage that evening. He too had no luck and returned the next morning. When the remaining rations, and all the local coconuts, had been consumed, the survivors investigated a small islet west of Cross Island and took cover in the heavy brush the next day. Undaunted by the sight of a New Zealand P-40 strafing Cross Island itself, Kennedy and Ross swam to that island in search of food, boats or anything which might prove useful to their party. At one point, the two men found a Japanese box with 30-40 bags of crackers and candy and, a little farther up the beach, a native lean-to with a one-man canoe and a barrel of water alongside. About this time a canoe with two natives was sighted but they paddled swiftly off despite all efforts to attract their attention. During the night of 5 August, Kennedy took the canoe into Ferguson Passage but found no PT boats. Returning home by way of Cross Island, where he picked up the food, he found the two natives there with the rest of the group. Ensign Thom, after telling them in as many ways as possible that he was an American and not a Japanese, had finally convinced the natives to help the Americans. The natives were then sent with messages to the coast watchers on Wana Wana, one was a pencilled note written the day before by Ensign Thom and the other a message written on a green coconut husk by Kennedy. The next day, eight natives arrived with instructions from the coast watcher for the senior naval officer to go with the natives to Wana Wana. After the natives dropped off food and other supplies, including a cook stove, they hid Kennedy under ferns in a large war canoe and paddled him to Wana Wana. The war canoe reached its destination about 1600 [4 p.m.] and later that night Kennedy made rendezvous in Ferguson Passage with PT-157, piloted by Lieutenant (jg) W. F. Liebenow. In company with PT-171, and guided by natives who knew passages through the reefs, the survivors were picked up by small boats later that evening. Everything went off smoothly and PT-157 returned the survivors to Rendova by morning. Lieutenant Kennedy was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal "for extremely heroic conduct as Commanding Officer of Motor Torpedo Boat 109 following the collision and sinking of that vessel in the Pacific War Area on August 1-2, 1943. Unmindful of personal danger, Lieutenant (then Lieutenant, junior grade) Kennedy unhesitatingly braved the difficulties and hazards of darkness to direct rescue operations, swimming many hours to secure aid and food after he had succeeded in getting his crew ashore. His outstanding courage, endurance and leadership contributed to the saving of several lives and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service." PT-109 earned two battle stars for the operations listed below: 1 Star/Capture and Defense of Guadalcanal:

7-8 December 1942; 13-15 January 1943; 1-2 February 1943. 1 Star/New Georgia Group Operation:

New Georgia-Rendova-Gangunu Occupation: 1-2 August1943. List of Commanding Officers Ensign Bryant L. Larson, USNR: 16 July 1942 - 20 April 1943. Ensign Leonard J. Thom, USNR: 20 April 1943 - 24 April 1943. Lieutenant (jg) John Fitzgerald Kennedy, USNR: 24 April 1943 - 2 August 1943. Combatant Features Motor torpedo boats, contrary to some beliefs, did not go seventy miles-per-hour nor did they launch torpedoes at high speed. PT-109 was a plywood boat measuring 80 feel in length and had a maximum beam [width] of 20 feet. Her maximum draft was six feet and she was powered by three 12-cylinder Packard engines, each of which developed 1,350 horse power. She could carry as many as four 21-inch torpedoes and originally mounted four .50 caliber machine guns in two twin mounts. One 20-mm was mounted on the fantail [aft or rear of boat] and small arms included submachine guns, rifles and 12-gauge shotguns. She could communicate with a blinker tube having an eight-inch searchlight, and by voice radio that had a range of 75 miles. Her maximum speed for a range of 358 miles was 35 knots (roughly 30 mph.). A full-load patrol speed of nine knots would he usual in covering a 600-mile range. Under ideal conditions, and after torpedoes have been fired, a maximum speed of approximately 46-knots (roughly 40 mph.) is possible. Her usual complement was three officers and nine men. | | | Declassified (8 SEP 59)

Subject: Sinking of PT 109 and subsequent rescue of survivors. Source: Survivors of PT 109. Narrative: On the night of August 1, fourteen boats were ordered into Blackett Strait from the Rendova PT base in anticipation of the Bougainville Express running into Vila. Four patrol sections were formed: 1st, under Lt. G. C. Cookman was stationed in Ferguson Passage; 2nd, under Lt. W. Rome, whose station was East of Makuti Island; 3rd, under Lt. A. H. Berndston stationed between Makuti Island and Kolombangara; and the 4th, the section in which PT 109 was a part, under Lt. E. J. Brantingham stationed five miles West of the 3rd section. Lt. Brantinghams' boats were further subdivided into two sections; PT 159, radar equipped, operating with PT 157, while PT 162, under the command of Lt.(jg) J. R. Lowrey, was the lead boat of the second section with PT 109 following. PTs 159 and 162 both carried TBYs for inter-boat communications. Instructions were issued to Lt.(jg) Jack Kennedy, captain of PT 109, to follow closely on PT 162's starboard quarter, which would keep in touch with the radar equipped PT 159 by TBY. [Portable radio equipment of low power used as emergency for TBS.] All boats departed from Rendova at 1830 and reached their patrol station about 2030. The 4th section patrolled without incident until gunfire and a searchlight were seen in the direction of the southern shore of Kolombangara. No radio or other warning had been received of enemy activity in the area. It was impossible to ascertain whether the searchlight came from shore or from a ship close into shore. Presumably it was not a ship as PT 162 retired on a westwardly course toward Gizo Strait. PT 109 followed and inquired as to the source of the firing. PT 162 replied that it was believed to be from a shore battery. However, PT 109 intercepted the following sudden terse radio message: "I am being chased through Ferguson Passage. Have fired fish". That was all, but it was enough to inform the group that an action with the enemy was in progress, and a significant one. At this time PT 169 came alongside to inquire about the firing in Blackett Strait and to report that one of her engines was out of order. PT 169 lay to with PTs 109 and 162 to await developments. In the meantime all contact with PT 109 had been lost. Instructions from base were requested and orders were received to resume normal patrol station. PT 162, being uncertain as to its position, requested PT 109 lead the way back to the patrol station, which it proceeded to do. When Lt. Kennedy thought he had reached the original patrol station, he started to patrol on one engine at idling speed. The time was about 0230. Ensign Ross was on the bow as lookout: Ensign Thom was standing beside the cockpit: Lt. Kennedy was at the wheel, and with him in the cockpit was McGuire, his radioman; Marney was in the forward turret; Mauer, the quartermaster was standing beside Ensign Thom; Albert was in the after turret; and McMann was in the engine room. The location of other members of the crew upon the boat is unknown. Suddenly a dark shape loomed up on PT 109's starboard bow 200-300 yards in the distance. At first this shape was believed to be other PTs. However, it was soon seen to be a [Japanese] destroyer identified as the Ribiki Group of the Fubuki Class bearing down on PT 109 at high speed. The 109 had started to turn to starboard preparatory to firing torpedoes. However, when PT 109 had scarcely turned 30, the destroyer rammed the PT, striking it forward of the forward starboard tube and shearing off the starboard side of the boat aft, including the starboard engine. The destroyer traveling at an estimated speed of 40 knots neither slowed nor fired as she split the PT, leaving part of the PT on one side and the other on the other. Scarcely 10 seconds elapsed between time of sighting and the crash.

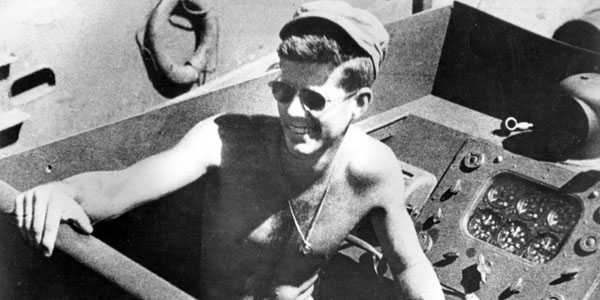

In April 1943, 25-year-old John F. Kennedy arrived in the Pacific and took command of the PT-109. Just months later, the boat collided with a Japanese ship, killing two of his men (John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library,

A fire was immediately ignited, but, fortunately, it was gasoline burning on the water's surface at least 20 yards away from the remains of the PT which were still afloat. This fire burned brightly for 15-20 minutes and then died out. It is believed that the wake of the destroyer carried off the floating gasoline there by saving PT 109 from fire. Lt. Kennedy, Ensigns Thom and Ross, Mauer, Mc McGuire and Albert still clung to the PT 109's hull. Lt. Kennedy ordered all hands to abandon ship when it appeared the fire would spread to it. All soon crawled back aboard when this danger passed. It was ascertained by shouting that Harris, McMahon and Starkey were in the water about 100 yards to the Southwest while Zinser and Johnson were an equal distance to the Southeast. Kennedy swam toward the group of three, and Thom and Ross struck out for the other two. Lt. Kennedy had to tow McMahon, who was helpless because of serious burns, back to the boat. A strong current impeded their progress, and it took about an hour to get McMahon aboard PT 109. Kennedy then returned for the other two men, one of whom was suffering from minor burns. He traded his life belt to Harris, who was uninjured in return for Harris's waterlogged kapok life jacket which was impeding the latters' swimming. Together they towed Starkey to the PT. Meanwhile, Ensigns Thom and Ross had reached Zinser and Johnson who were both helpless because of gas fumes. Thom towed Johnson, and Ross took Zinser and Johnson who were both helpless because of gas fumes. Thom towed Johnson, and Ross took Zinser. Both regained full consciousness by the time the boat was reached. Within three hours after the crash all survivors who could be located were brought aboard PT 109. Marney and Kirksey were never seen after the crash. During the three hours it took to gather the survivors together, nothing was seen or heard that indicated other boats or ships in the area. PT 109 did not fire its Very pistols for fear of giving away its position to the enemy. Meanwhile the IFF [Identification, friend or foe] and all codes aboard had either been completely destroyed or sunk in the deep waters of Vella Gulf. Despite the fact that all water- tight doors were dogged down at the time of the crash, PT 109 was slowly taking on water. When daylight of August 2 arrived, the eleven survivors were still aboard PT 109. It was estimated that the boat lay about 4 miles north and slightly east of Gizo Anchorage and about 3 miles away from the reef along northeast Gizo. It was obvious that the PT 109 would sink on the 2nd, and decision was made to abandon it in time to arrive before dark on one of the tiny islands east of Gizo. A small island 3 1/2 - 4 miles to the southeast of Gizo was chosen on which to land, rather than one but 2 1/2 miles away which was close to Gizo, and, which, it was feared, might be occupied by the Japs. At 1400 Lt. Kennedy took the badly burned McMahon in tow and set out for land, intending to lead the way and scout the island in advance of the other survivors. Ensigns Ross and Thom followed with the other men. Johnson and Mauer, who could not swim, were tied to a float rigged from a 2 x 8 which was part of the 37 mm gun mount. Harris and McGuire were fair swimmers, but Zinser, Starkey and Albert were not so good. The strong swimmers pushed or towed the float to which the non-swimmers were tied. Lt. Kennedy was dressed only in skivvies, Ensign Thom, coveralls and shoes, Ensign Ross, trousers, and most of the men were dressed only in trousers and shirts. There were six 45s' in the group (two of which were later lost before rescue), one 38, one flashlight, one large knife, one light knife and a pocket knife. The boats first aid kit had been lost in the collision. All the group with the exception of McMahon, who suffered considerably from burns, were in fairly good condition, although weak and tired from their swim ashore. That evening Lt. Kennedy decided to swim into Ferguson Passage in an attempt to intercept PT boats proceeding to their patrol areas. He left about 1830, swam to a small island 1/2 mile to the southeast, proceeded along a reef which stretched out into Ferguson Passage, arriving there about 2000. No PTs were seen, but aircraft flares were observed which indicated that the PTs that night were operating in Gizo not Blackett Strait and were being harassed as usual by enemy float planes. Kennedy began his return over the same route he had previously used. While swimming the final lay to the island on which the other survivors were, he was caught in a current which swept him in a circle about 2 miles into Blackett Strait and back to the middle of Ferguson Passage, where he had to start his homeward trip all over again. On this trip he stopped on the small island just southeast of "home" where he slept until dawn before covering the last 1/2 mile lap to join the rest of his group. He was completely exhausted, slightly feverish, and slept most of the day. Nothing was observed on August 2 or 3 which gave any hope of rescue. On the night of the 3rd Ensign Ross decided to proceed into Ferguson Passage in another attempt to intercept PT patrols from Rendova. Using the same route as Kennedy had used and leaving about 1800, Ross "patrolled" off the reefs on the west side of the Passage with negative results. In returning he wisely stopped on the islet southeast of "home", slept and thereby avoided the experience with the current which had swept Kennedy out to sea. He made the final lap next morning. The complete diet of the group on what came to be called Bird Island (because of the great abundance of droppings from the fine feathered friends) consisted of coconut milk and meat. As the coconut supply was running low and in order to get closer to Ferguson Passage, the group left Bird Island at noon, August 4th, and using the same arrangements as before, headed for a small islet west of Cross Island. Kennedy, with McMahon in tow arrived first. The rest of the group again experienced difficulty with a strong easterly current, but finally managed to make the eastern tip of the island. Their new home was slightly larger than their former, offered brush for protection and a few coconuts to eat, and had no Jap tenants. The night of August 4th was wet and cold, and no one ventured into Ferguson Passage that night. The next morning Kennedy and Ross decided to swim to Cross Island in search of food, boats or anything else which might be useful to their party. Prior to their leaving for Cross Island, one of three New Zealand P-40s made a strafing run on Cross Island. Although this indicated the possibility of Japs, because of the acute food shortage, the two set out, swam the channel and arrived on Cross Island about 1530. Immediately the ducked into the brush. Neither seeing nor hearing anything, the two officers sneaked through the brush to the east side of the island and peered from the brush onto the beach. A small rectangular box with Japanese writing on the side was seen which was quickly and furtively pulled into the bush. Its contents proved to be 30-40 small bags of crackers and candy. A little farther up the beach, alongside a native lean-to, a one-man canoe and a barrel of water were found. About this time a canoe containing two persons was sighted. Light showing between their legs revealed that they did not wear trousers and, therefore, must be natives. Despite all efforts of Kennedy and Ross to attract their attention, they paddled swiftly off to the northwest. Nevertheless, Kennedy and Ross, having obtained a canoe, for and water, considered their visit a success. That night Kennedy took the canoe and again proceeded into Ferguson Passage, waited there until 2100, but again no PTs appeared. He returned to his "home" island via Cross Island where he picked up the food but left Ross who had decided to swim back the following morning. When Kennedy arrived at base at about 2330, he found that the two natives which he and Ross had sighted near Cross Island, had circled around and landed on the island where the rest of the group were. Ensign Thom, after telling the natives in as many ways as possible that he was an American and not a Jap, finally convinced them whereupon they landed and performed every service possible for the survivors. The next day, August 6, Kennedy and the natives paddled to Cross Island intercepting Ross, who was swimming back to the rest of the group. After Ross and Kennedy had thoroughly searched Cross Island for Japs and found none, despite the natives' belief to the contrary, they showed the two PT survivors where a two-man native canoe was hidden. The natives were then sent with messages to the Coastwatcher. One was a penciled note written the day before by Ensign Thom; the other was a message written on a green coconut husk by Kennedy, informing the Coastwatcher that he and Ross were on Cross Island. After the natives left, Ross and Kennedy remained on the island until evening, when they set in the two-man canoe to again try their luck at intercepting PTs in Ferguson Passage. They paddled far out into Ferguson Passage, saw nothing, and were caught in a sudden rain squall which eventually capsized the canoe. Swimming to land was difficult and treacherous as the sea swept the two officers against the reef on the south side of Cross Island. Ross received numerous cuts and bruises, but both managed to make land where they remained the rest of the night. On Saturday, August 7, eight natives arrived, bringing a message from the Coastwatcher instructing the senior officer to go with the natives to Wana Wana. Kennedy and Ross had the natives paddle them to island where the rest of the survivors were. The natives had brought food and other articles (including a cook stove) to make the survivors comfortable. They were extremely kind at all times. That afternoon, Kennedy, hidden under ferns in the native boat, was taken to the Coastwatcher, arriving about 1600. There it was arranged that PT boats would rendezvous with him in Ferguson Passage that evening at 2330. Accordingly he was taken to the rendezvous point and finally managed to make contact with the PTs at 2315. He climbed aboard the PT and directed it to the rest of the survivors. The rescue was effected without mishap, and the Rendova base was reached at 0530, August 8, seven days after the ramming of the PT 109 in Blackett Strait. When Kennedy took charge of PT-109, on April 25, 1943, he was already a millionaire heir, society figure, and ambassador's son (see photo). But fame and fortune were scarce comfort to him on August 2, 1943. That night at about 2 a.m., the Japanese destroyer Amagiri (see photo), by accident or by design, bisected the much smaller PT-109 (see size comparison), killing two of Kennedy's crew.

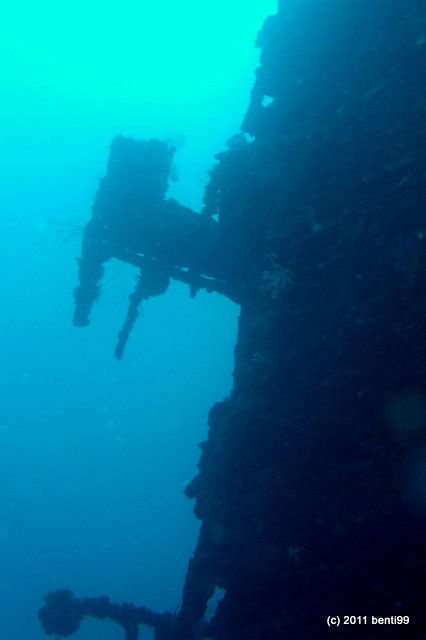

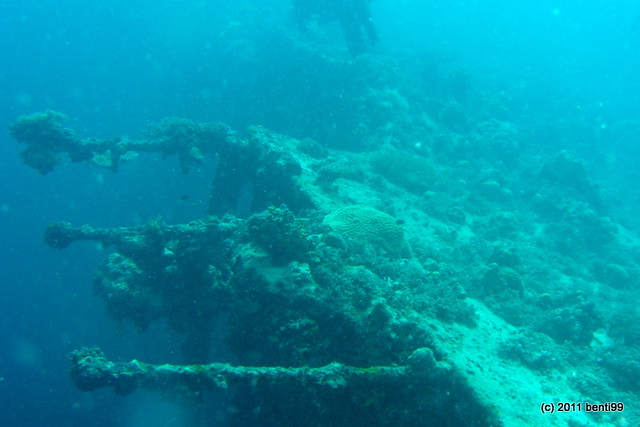

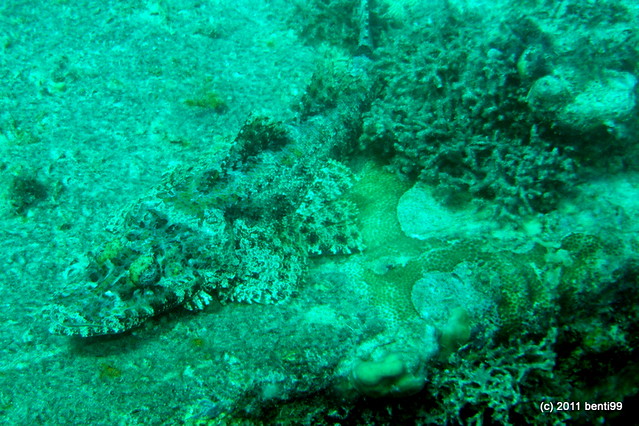

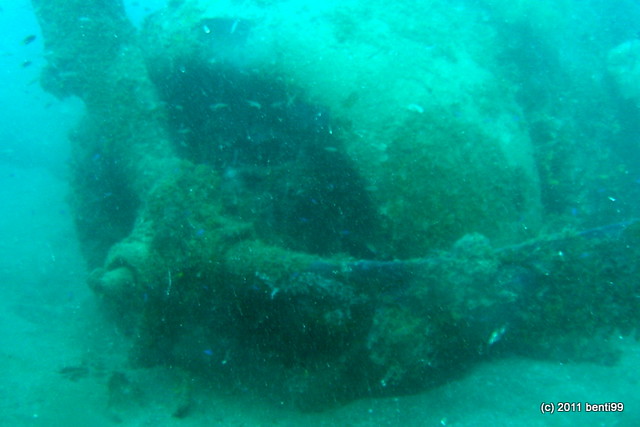

A torpedo from John F. Kennedy's PT-109 rests some 1,200 feet (360 meters) underwater in the Solomon Islands. Key details from the torpedo and its nearby launching tube helped identify this wreck site as that of the World War II boat. The jury-rigged scraper in the foreground was attached to a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and dubbed STUPID (sediment transport unit piloted in depth) by the search team. It was used in a fruitless attempt to clear away sand and reveal more remains of PT-109.

After drifting on PT-109's still-floating bow overnight, Kennedy and the other shipwreck survivors—several of them injured—swam for several hours to reach this tiny island, shown with much larger Kolombangara in the background. Now known as Kennedy Island, the deserted atoll was then called Plum Pudding. Despite its lush appearance, Plum Pudding was lacking in food and devoid of fresh water, and the survivors were soon weary from heat, hunger, and most of all, thirst. After two nights on their first island refuge, the PT-109 survivors risked the swim to another island—one with more coconuts, sources of much-needed food and water. The survivors swam some two miles (three kilometers) to Olasana Island (right), shown much as they would have seen it as they began their swim. At left is Naru Island, where Kennedy first encountered the Solomon Islanders who would play a pivotal role in his rescue. The Australia-based fishing boat Grayscout was chartered for the May 2002 PT-109 expedition and temporarily converted to a shipwreck-search vessel. The green container on deck, which serves as an onboard ROV repair shop, was transported from the U.S. via cargo ship to Australia. Both expedition ROVs, including lighting rig Argus(shown suspended from the rear of the ship), arrived inside the container. << Kennedy spent the rest of the night helping rescue injured and wave-tossed crew members (see photo). By dawn the survivors were all clinging to the still-floating bow. By afternoon they were making a several-hour swim—the strong towing the injured—to a deserted island (see photo). Despite a back injury, Kennedy himself pulled the worst case, tugging the sailor's life vest with his teeth. The following days (see detailed time line at right) saw several fearless attempts to be rescued. The men were weary with starvation and thirst, when they were eventually rescued by Solomon Islanders loyal to the Allies. The islanders could operate in daylight without arousing Japanese suspicion, and many served as scouts for Allied coastwatchers operating behind enemy lines. Two of them helped deliver to a coastwatcher a coconut Kennedy famously carved with a rescue message. After receiving messages from the 109 crew, the coastwatcher radioed the PT base to arrange a rescue. Six days after their stranding, Kennedy and crew were safe aboard a sister ship, PT-157. (Hear a firsthand account of the rescue from PT-157's Welford West.) The PT-109 survival story passed into popular culture and became perhaps Kennedy's greatest political asset. Kennedy the President had a PT-109 float in his inaugural parade, doled out 109 tiepins to visitors, and kept his medals on permanent display. And on his Oval Office desk sat, lacquered and almost illegible, the world's most important coconut. Photos of my trip to the Solomons 2002..ASC

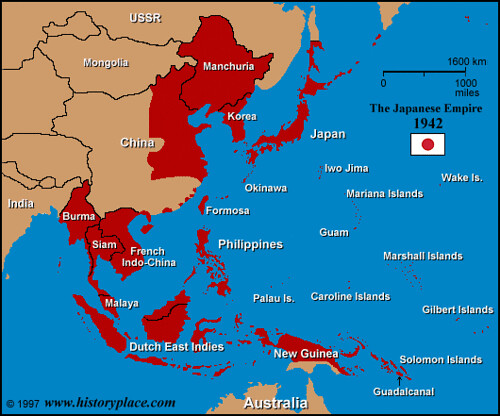

The Solomon Islands is a nation in Melanesia, east of Papua New Guinea, consisting of nearly one thousand islands. Together they cover a land mass of 28,400 square kilometres (10,965 sq mi). The capital is Honiara, located on the island of Guadalcanal. The Japanese defeat at the Battle of Midway had forced planners in the Imperial Army to reconsider their plans of expansion and to concentrate their forces on consolidating the territory that they had captured. The victory at Midway was also a turning point for the Americans as after this battle, they could think in terms of re-capturing taken Pacific islands - the first confrontation was to be at Guadalcanal.

Guadalcanal is part of the Solomon Islands which lie to the north-eastern approaches of Australia. Though it is a humid and jungle-covered tropical island its position made it strategically important for both sides in the Pacific War. If the Japanese captured the island, they could cut off the sea route between Australia and America. If the Americans controlled the island, they would be better able to protect Australia from Japanese invasion and they could also protect the Allied build-up in Australia that would act as a springboard for a major assault on the Japanese. Shores of Guadalcanal. Becalmed upon the sea of Thought,

Still unattained the land it sought,

My mind, with loosely-hanging sails,

Lies waiting the auspicious gales. No stone tells the place where their ashes repose,

Nor points out the spot from the graves of their foes.

They died in their glory, surrounded by fame,

And Victory's loud trump their death did proclaim; The Japanese hierarchy in Tokyo refused to admit defeat and ordered yet more men to Guadalcanal. In mid-November 1942, planes from Henderson attacked a convoy of ships bringing Japanese reinforcements to Guadalcanal. Of eleven transport ships, six were sunk, one was severely damaged and four had to be beached. Only 2,000 men ever reached Guadalcanal - but few had any equipment as this had been lost at sea. On December 1942, the emperor ordered a withdrawal from Guadalcanal. This withdrawal took place from January to February 1943 and the Americans learned that even in defeat that the Japanese were a force to be reckoned with. 11,000 Japanese soldiers were taken off the island in the so-called 'Tokyo Night Express'. On January 2, 1976, the Solomons became self-governing, and independence followed on July 7, 1978, the first post-independence government was elected in August 1980. The series of governments formed from there on have not performed to upgrade and build the country. Following the 1997 election of Bartholomew Ulufa'alu the political situation in the Solomon's began to deteriorate. This is why we were not allowed to go ashore in these islands. November 20, 1943: Under attack from Japanese machine gun fire on the right flank, men of the 165th Infantry are seen as the wade through coral bottom water on Yellow Beach Two, Butaritari, during the assault on the Makin atoll, Gilbert Islands. (AP Photo)

Nov. 4, 1942: Two alert U.S. Marines stand beside their small tank on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands during World War II. The military tank was used against the Japanese in the battle of the Tenaru River during the early stages of fighting. (AP Photo) Jan. 21, 1943: Native stretcher bearers rest in the shade of a coconut grove as they and the wounded American soldiers they are carrying from the front lines at Buna, New Guinea take the opportunity to relax. The wounded are on their way to makeshift hospitals in the rear. (AP Photo) January 1943: While on a bombing run over Salamau, New Guinea, before its capture by Allied forces, photographer Sgt. John A. Boiteau aboard an army Liberator took this photograph of a B-24 Liberator during World War II. Bomb bursts can be seen below in lower left and a ship at upper right along the beach. (AP Photo/U.S. Army Force) Aug. 1942: U.S. Marines approach the Japanese occupied Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands during World War II. (AP Photo) | |

This is infamous Henderson Field, the airstrip that was under constant Japanese bombardment and American repair from August 20 to end of November 1942. US SeaBees (Naval Construction Battalions) ensured that the strip could be used by own fighters and bombers to hold the Japanese from landing reinforcements and equipment

This is infamous Henderson Field, the airstrip that was under constant Japanese bombardment and American repair from August 20 to end of November 1942. US SeaBees (Naval Construction Battalions) ensured that the strip could be used by own fighters and bombers to hold the Japanese from landing reinforcements and equipment

PT 109 commanded by Kennedy with executive officer, Ensign Leonard Jay Thom, and ten enlisted men was one of the fifteen boats sent out on patrol on the night of 1-2 August 1943 to intercept Japanese warships in the straits. A friend of Kennedy, Ensign George H. R. Ross, whose ship was damaged, joined Kennedy's crew that night. The PT boat was creeping along to keep the wake and noise to a minimum in order to avoid detection. Around 0200 with Kennedy at the helm, the Japanese destroyer Amagiri traveling at 40 knots cut PT 109 in two in ten seconds. Although the Japanese destroyer had not realized that their ship had struck an enemy vessel, the damage to PT 109 was severe. At the impact, Kennedy was thrown into the cockpit where he landed on his bad back. As Amagiri steamed away, its wake doused the flames on the floating section of PT 109 to which five Americans clung: Kennedy, Thom, and three enlisted men, S1/c Raymond Albert, RM2/c John E. Maguire and QM3/c Edman Edgar Mauer. Kennedy yelled out for others in the water and heard the replies of Ross and five members of the crew, two of which were injured. GM3/c Charles A. Harris had a hurt leg and MoMM1/c Patrick Henry McMahon, the engineer was badly burned. Kennedy swam to these men as Ross and Thom helped the others, MoMM2/c William Johnston, TM2/c Ray L. Starkey, and MoMM1/c Gerald E. Zinser to the remnant of PT 109. Although they were only one hundred yards from the floating piece, in the dark it took Kennedy three hours to tow McMahon and help Harris back to the PT hulk. Unfortunately, TM2/c Andrew Jackson Kirksey and MoMM2/c Harold W. Marney were killed in the collision with Amagiri.

PT 109 commanded by Kennedy with executive officer, Ensign Leonard Jay Thom, and ten enlisted men was one of the fifteen boats sent out on patrol on the night of 1-2 August 1943 to intercept Japanese warships in the straits. A friend of Kennedy, Ensign George H. R. Ross, whose ship was damaged, joined Kennedy's crew that night. The PT boat was creeping along to keep the wake and noise to a minimum in order to avoid detection. Around 0200 with Kennedy at the helm, the Japanese destroyer Amagiri traveling at 40 knots cut PT 109 in two in ten seconds. Although the Japanese destroyer had not realized that their ship had struck an enemy vessel, the damage to PT 109 was severe. At the impact, Kennedy was thrown into the cockpit where he landed on his bad back. As Amagiri steamed away, its wake doused the flames on the floating section of PT 109 to which five Americans clung: Kennedy, Thom, and three enlisted men, S1/c Raymond Albert, RM2/c John E. Maguire and QM3/c Edman Edgar Mauer. Kennedy yelled out for others in the water and heard the replies of Ross and five members of the crew, two of which were injured. GM3/c Charles A. Harris had a hurt leg and MoMM1/c Patrick Henry McMahon, the engineer was badly burned. Kennedy swam to these men as Ross and Thom helped the others, MoMM2/c William Johnston, TM2/c Ray L. Starkey, and MoMM1/c Gerald E. Zinser to the remnant of PT 109. Although they were only one hundred yards from the floating piece, in the dark it took Kennedy three hours to tow McMahon and help Harris back to the PT hulk. Unfortunately, TM2/c Andrew Jackson Kirksey and MoMM2/c Harold W. Marney were killed in the collision with Amagiri.  A

A

The sound between the Nggela Islands and Guadalcanal, called "Iron Bottom Sound" for the number of warships sunk there, was geographically favorable for PT operations. The two western entrances, one between Cape Esperance and Savo Island to the south; and the other, between Savo Island and Sandfly Passage to the north, were relatively narrow. Finally, the western tip of Guadalcanal was less than thirty-five miles across sheltered water from the PT base at Sesapi.

The sound between the Nggela Islands and Guadalcanal, called "Iron Bottom Sound" for the number of warships sunk there, was geographically favorable for PT operations. The two western entrances, one between Cape Esperance and Savo Island to the south; and the other, between Savo Island and Sandfly Passage to the north, were relatively narrow. Finally, the western tip of Guadalcanal was less than thirty-five miles across sheltered water from the PT base at Sesapi.

No comments:

Post a Comment