THE ST. NAZAIRE RAID |

|

|

| THE GREATEST RAID OF ALL "What a story it is, straight out of a Commando comic book." the guardian Jeremy Clarkson tells the story of one of the most daring operations of World War II -- the Commando raid on the German occupied dry dock at St. Nazaire in France on 28th March 1942. It was an operation so successful and so heroic that it resulted in the award of five Victoria Crosses and 80 other decorations for gallantry. | The Most Courageous Raid of WWII |

|  |

| The St Nazaire Raid or Operation Chariot was a successful British amphibious attack on the heavily defended Normandie dry dock atSt Nazaire in German-occupied France during the Second World War. The operation was undertaken by the Royal Navy and British Commandos under the auspices of Combined Operations Headquarters on 28 March 1942. St Nazaire was targeted because the loss of its dry dock would force any large German warship in need of repairs, such as the Tirpitz, to return to home waters rather than having a safe haven available on the Atlantic coast. The obsolete destroyer HMS Campbeltown, accompanied by 18 smaller craft, crossed the English Channel to the Atlantic coast of France and was rammed into the Normandie dock gates. The ship had been packed with delayed-action explosives, well hidden within a steel and concrete case, that detonated later that day, putting the dock out of service for the remainder of the war and up to ten years after. A force of commandos landed to destroy machinery and other structures. Heavy German gunfire sank, set ablaze or immobilised all the small craft intended to transport the commandos back to England; the commandos had to fight their way out through the town to try to escape overland. They were forced to surrender when their ammunition was expended and they were surrounded. After the raid 228 men of the force of 622 returned to Britain; 169 were killed and 215 became prisoners of war. German casualties were over 360 dead, mostly killed after the raid when Campbeltown exploded. To recognise their bravery, 89 decorations were awarded to members of the raiding party, including five Victoria Crosses. After the war St Nazaire was one of 38 battle honours awarded to the Commandos; the operation has since become known as The Greatest Raid of All. |

The start of Word War II. German invasion of Poland. September '39. German motorized troops on the streets of Warsaw. |

| The Allied governments declared war on Germany on 3 September; however, they failed to provide any meaningful support. The German-French border saw only a few minor skirmishes, although the majority of German forces, including 85% of their armoured forces, were engaged in Poland. Despite some Polish successes in minor border battles, German technical, operational and numerical superiority forced the Polish armies to retreat from the borders towards Warsaw and Lwów. The Luftwaffe gained air superiority early in the campaign. By destroying communications, the Luftwaffe increased the pace of the advance which overran Polish airstrips and early warning sites, causing logistical problems for the Poles. Many Polish Air Force units ran low on supplies, 98 of their number withdrew into then-neutral Romania. The Polish initial strength of 400 was reduced to just 54 by 14 September and air opposition virtually ceased. By 3 September, when Günther von Kluge in the north had reached the Vistula river (some 10 km (6.2 mi) from the German border at that time) and Georg von Küchler was approaching the Narew River, Walther von Reichenau's armor was already beyond the Warta river; two days later, his left wing was well to the rear of Łódź and his right wing at the town of Kielce. By 8 September, one of his armored corps—having advanced 225 km (140 mi) in the first week of the campaign—reached the outskirts of Warsaw. Light divisions on Reichenau's right were on the Vistula between Warsaw and the town of Sandomierz by 9 September while List—in the south—was on the San River above and below the town of Przemyśl. At the same time, Guderian led his 3rd Army tanks across the Narew, attacking the line of the Bug River, already encircling Warsaw. All the German armies made progress in fulfilling their parts of the Fall Weiss plan. The Polish armies were splitting up into uncoordinated fragments, some of which were retreating while others were launching disjointed attacks on the nearest German columns.

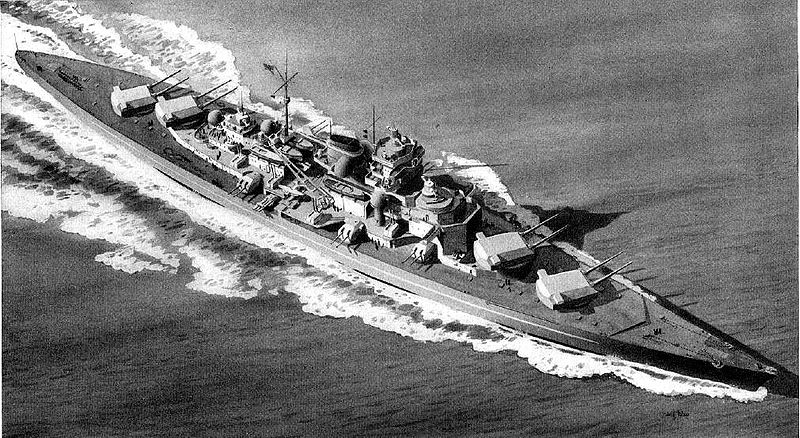

Cheerful German and Slovak soldiers posing with Ukrainian civilians in Komańcza, September 1939. |  In the course of the warship's short eight month career under its only commanding officer, Capt. Ernst Lindemann, Bismarck conducted only one offensive operation, in May 1941, codenamed Rheinübung. The ship, along with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, was to break into the Atlantic Ocean and raid Allied shipping from North America to Great Britain. The two ships were detected several times off Scandinavia, however, and British naval units were deployed to block their route. At the Battle of Denmark Strait, Bismarck engaged and destroyed the battlecruiser HMS Hood, the pride of the Royal Navy, and forced the battleship HMS Prince of Wales to retreat with heavy damage, although Bismarck herself was hit three times and suffered an oil leak from a ruptured tank. |

On 24 May 1941, the Battle of the Denmark Strait was fought between the German ships Bismarck and Prinz Eugen and the British ships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Hood. Hood was sunk and the damaged Prince of Wales was forced to retire. Bismarck, also damaged, ordered her consort to proceed independently while she headed for the French port of St Nazaire, which was the only port on the Atlantic coast with a drydock able to accommodate a ship of her size. She was intercepted by the British and sunk en route.

Britain's Naval Intelligence Division first proposed a commando raid on the dock in late 1941.When the German battleship Tirpitz was declared operational in January 1942, the Royal Navy (RN) and Royal Air Force (RAF) were already drawing up plans to attack her. Planners from Combined Operations Headquarters were looking at potential scenarios if Tirpitz escaped the naval blockade and reached the Atlantic.They decided the only port able to accommodate her was St Nazaire, especially if, like the Bismarck, she was damaged en route and needed repairs. They came to the conclusion that if the dock at St Nazaire was unavailable the Germans were unlikely to risk sending Tirpitz into the Atlantic.

SS Normandie in her namesake dock

Combined Operations examined a number of options while planning the destruction of the dock. At this stage of the war the British government still tried to avoid civilian casualties. This ruled out a bombing attack by the RAF, which at the time did not possess the accuracy needed to destroy the dock without serious loss of civilian life.[7] The Special Operations Executive were approached to see if its agents could destroy the dock gates. They decided that the mission was beyond their capabilities because the weight of explosives required too many agents just to carry them.[8] The RN were also unable to mount an operation, as St Nazaire is 8 km (5 miles) up the Loire estuary. Any naval ships large enough to cause sufficient damage would be detected well before they were within range.[7]

The planners then examined whether a commando force could be used. There was an unusually high spring tide due in March 1942, which would allow a light ship to pass over the sand banks in the estuary and approach the docks, bypassing the dredged and presumably well-defended channel. It would still be too shallow for infantry landing ships, but specially lightened destroyers might succeed

The purpose of the raid was to destroy three objectives: the Normandie dock, the old gates into the Basin de St Nazaire together with the water pumping machinery and other installations, and any U-boats or other shipping in the area. The initial Combined Operations plan required two specially lightened destroyers to carry out the raid. The first would be packed with explosives and rammed into the dock gates. Commandos on board would then disembark and use demolition charges to destroy nearby dock installations, searchlights and gun emplacements. The destroyer would then be blown up, and the second ship would come in and evacuate the ship's crew and the commandos. At the same time the RAF would carry out a number of diversionary air raids in the area.

When the plan was presented to the Admiralty, they refused to support it. The certain loss of one or both destroyers to eliminate the dry dock was out of the question. They suggested they could provide an old Free French ship, the Ouragan and a flotilla of small motor launches to transport the commandos and evacuate them afterwards.[9] Approval for the mission, codenamed Operation Chariot, was given on 3 March 1942. Using a French ship would involve using the Free French forces and increase the number of people aware of the raid. Consequently it was decided the navy would have to provide a ship of their own. The RAF complained that the raid would draw heavily on their resources; the number of aircraft assigned by RAF Bomber Command was reduced time and again before the day of the raid. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill further complicated matters when he ordered that bombing should only take place if targets were clearly identified.

The St. Nazaire U-boat pens in 2005

Combined Operations Headquarters worked closely with several intelligence organisations to plan the raid. The Naval Intelligence Division compiled information from a variety of sources. A detailed plan of the town of St Nazaire was provided by the Secret Intelligence Service, and information on the coastal artillery nearby was sourced from the War Office's Military Intelligence branch. Intelligence about the dock itself came from pre-war technical journals. The RN's Operational Intelligence Centre selected the route and timing for the raid based on intelligence about the location of minefields and German recognition signals sourced from Enigma decrypts and knowledge of Luftwaffe patrols compiled by the Air Ministry's Air Intelligence Branch.[5]When all the plans had been pulled together and the timing worked out, the raid was expected to last no longer than two hours. The commandos and crew from Campbeltown would board the motor launches at the Old Mole jetty and then return to base.

Associated Press correspondent Alvin Steinkopf broadcasting from the Free City of Danzig -- at the time, a semi-autonomous city-state tied to Poland. Steinkopf was relating the tense situation in Danzig back to America, on July 11, 1939. Germany had been demanding the incorporation of Danzing into the Third Reich for months, and appeared to be preparing military action. (AP Photo) #

Soviet premier Josef Stalin (second from right), smiles while Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (seated), signs the non-aggression pact with German Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop (third from right), in Moscow, on August 23, 1939. The man at left is Soviet Deputy Defense Minister and Chief of the General Staff, Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov. The nonaggression pact included a secret protocol dividing eastern Europe into spheres of influence in the event of a conflict. The pact now guaranteed that Hitler's troops would face no resistance from the Soviets if they invaded Poland, bringing the war one step closer to reality. (AP Photo/File) #

Two days after Germany signed the non-aggression pact with the USSR, Great Britain entered into a military alliance with Poland, on August 25, 1939. This photo shows the scene one week later, on September 1, 1939, one of the first military operations of Germany's invasion of Poland, and the beginning of World War II. Here, the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein is bombing a Polish military transit depot at Westerplatte in the Free City of Danzig. Simultaneously, the German Air Force (Luftwaffe), and ground troops (Heer) were attacking several other Polish targets. (AP Photo) #

German soldiers comb the Westerplatte after it was surrendered to German units from the Schleswig-Holstein landing crew, on September 7, 1939. Fewer than 200 Polish soldiers defended the small peninsula, holding off the Germans for seven days. (AP Photo) #

Aerial view of bombs exploding during a German bombing run over Poland in September of 1939 (LOC) #

Two tanks of the SS-Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Division cross the Bzura River during the German invasion of Poland in September of 1939. The Battle of Bzura, the largest of the entire campaign, lasted more than a week, ending with the German forces capturing most of western Poland. (LOC/Klaus Weill) #

Soldiers of the SS-Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Division, resting in a ditch alongside a road on the way to Pabianice, during the invasion of Poland in 1939. (LOC/Klaus Weill) #

Warning:

This image may contain graphic or

objectionable content

Click to view image

A ten-year-old Polish girl named Kazimiera Mika mourns over her sister's body. She was killed by German machine-gun fire while picking potatoes in a field outside Warsaw, Poland, in September of 1939. (AP Photo/Julien Bryan) #

German advance guards and scouts are shown in a Polish town that has been under fire during the Nazi invasion of Poland, September 1939. (AP Photo) #

German infantry cautiously advance on the outskirts of Warsaw, Poland on September 16, 1939. (AP Photo) #

Several civilian prisoners of war, with arms raised, walk along a road during the German invasion of Poland in September of 1939. (LOC) #

Britain's King George VI broadcasts to the British nation on the first evening of the war, on September 3, 1939, in London. (AP Photo) #

A conflict which would end with the dropping of two nuclear bombs began with a proclamation read aloud by a town crier. Acting Town Crier and Saltbearer of the City of London, W.T. Boston, reads the war proclamation from the steps of the Royal Exchange, in London, on September 4, 1939. (AP Photo/Putnam) #

A crowd reads newspaper headlines, "Bombs Rain On Warsaw" as they stand outside the U.S. State Department building where diplomats held a conference on war conditions in Europe, on September 1, 1939. (AP Photo) #

On September 17, 1939, the Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Courageous was hit by torpedoes from the German submarine U-29, and sank within 20 minutes. The Courageous, on an anti-submarine patrol off the coast of Ireland, was stalked for hours by U-29, which launched three torpedoes when it saw an opening. Two of the torpedoes struck the ship on the port side, sinking it with the loss of 518 of its 1,259 crew members. (AP Photo) #

The scene of devastation seen on Ordynacka Street in Warsaw, Poland on March 6, 1940. The carcass of a dead horse lies in the street among enormous piles of debris. While Warsaw was under nearly constant bombardment during the invasion, on one day alone, September 25, 1939, about 1,150 bombing sorties were flown by German aircraft against Warsaw, dropping over 550 tons of high explosive and incendiary bombs on the city. (AP Photo) #

Warning:

This image may contain graphic or

objectionable content

Click to view image

German troops marching into the city of Bromberg (the German name for the Polish city of Bydgoszcz) found several hundred German nationals dead from Polish sniper fire. The snipers were equipped with arms by the retreating Polish forces. Bodies are shown on a forest road, September 8, 1939. (AP Photo) #

A damaged Polish armored train carrying tanks captured by the 14th SS-Leibstandard Adolf Hitler Division, near Blonie, during the invasion of Poland in September of 1939. (LOC/Klaus Weill) #

German soldiers, taken prisoner by the Polish army during the Nazi invasion, are shown while they were held captive in Warsaw, on October 2, 1939. (AP Photo) #

A young Polish boy returns to what was his home and squats among the ruins during a pause in the German air raids on Warsaw, Poland, in September of 1939. German attacks lasted until Warsaw surrendered on September 28. One week later, the last of the Polish forces capitulated near Lublin, giving full control of Poland to Germany and the Soviet Union. (AP Photo/Julien Bryan) #

Adolf Hitler salutes parading troops of the German Wehrmacht in Warsaw, Poland, on October 5, 1939 after the German invasion. Behind Hitler are, from left to right: Colonel General Walther von Brauchitsch, Lieutenant General Friedrich von Cochenhausen, Colonel General Gerd von Rundstedt, and Colonel General Wilhelm Keitel. (AP Photo)

| German Wehrmacht General Anton Dostler is tied to a stake before his execution by a firing squad in a stockade in Aversa, Italy, on December 1, 1945. The General, Commander of the 75th Army Corps, was sentenced to death by an United States Military Commission in Rome for having ordered the shooting of 15 unarmed American prisoners of war, in La Spezia, Italy, on March 26, 1944. (AP Photo) |

| The St Nazaire Raid or Operation Chariot was a successful British amphibious attack on the heavily defended Normandie dry dock atSt Nazaire in German-occupied France during the Second World War. The operation was undertaken by the Royal Navy and British Commandos under the auspices of Combined Operations Headquarters on 28 March 1942. St Nazaire was targeted because the loss of its dry dock would force any large German warship in need of repairs, such as the Tirpitz, to return to home waters rather than having a safe haven available on the Atlantic coast. The obsolete destroyer HMS Campbeltown, accompanied by 18 smaller craft, crossed the English Channel to the Atlantic coast of France and was rammed into the Normandie dock gates. The ship had been packed with delayed-action explosives, well hidden within a steel and concrete case, that detonated later that day, putting the dock out of service for the remainder of the war and up to ten years after. A force of commandos landed to destroy machinery and other structures. Heavy German gunfire sank, set ablaze or immobilised all the small craft intended to transport the commandos back to England; the commandos had to fight their way out through the town to try to escape overland. They were forced to surrender when their ammunition was expended and they were surrounded. After the raid 228 men of the force of 622 returned to Britain; 169 were killed and 215 became prisoners of war. German casualties were over 360 dead, mostly killed after the raid when Campbeltown exploded. To recognise their bravery, 89 decorations were awarded to members of the raiding party, including five Victoria Crosses. After the war St Nazaire was one of 38 battle honours awarded to the Commandos; the operation has since become known as The Greatest Raid of All. St Nazaire is on the north bank of the Loire 400 km (250 miles) from the nearest British port, it had a population of 50,000 in 1942. The St Nazaire port has an outer harbour known as the Avant Port, formed by two piers jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean. This leads to two lock gates before the Basin de St Nazaire. These gates control the water level in the basin so that it is not affected by the tide. Beyond the basin is the larger inner dock called the Basin de Penhoët, which can accommodate ships up to 10,000 tons. There is also an old entrance to the Basin de St Nazaire located northwest of the Normandie dry dock. Built to house the ocean liner SS Normandie, this dock was the largest dry dock in the world when it was completed in 1932.[3] The "Old Mole" jetty juts into the Loire halfway between the southern pier of the Avant Port and the old entrance into the basin.[4] On 24 May 1941, the Battle of the Denmark Strait was fought between the German ships Bismarck and Prinz Eugen and the British ships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Hood. Hood was sunk and the damaged Prince of Wales was forced to retire. Bismarck, also damaged, ordered her consort to proceed independently while she headed for the French port of St Nazaire, which was the only port on the Atlantic coast with a drydock able to accommodate a ship of her size. She was intercepted by the British and sunk en route.[3] Britain's Naval Intelligence Division first proposed a commando raid on the dock in late 1941.[5] When the German battleship Tirpitz was declared operational in January 1942, the Royal Navy (RN) and Royal Air Force (RAF) were already drawing up plans to attack her. Planners from Combined Operations Headquarters were looking at potential scenarios if Tirpitz escaped the naval blockade and reached the Atlantic.[6] They decided the only port able to accommodate her was St Nazaire, especially if, like the Bismarck, she was damaged en route and needed repairs. They came to the conclusion that if the dock at St Nazaire was unavailable the Germans were unlikely to risk sending Tirpitz into the Atlantic.[6] SS Normandie in her namesake dock Combined Operations examined a number of options while planning the destruction of the dock. At this stage of the war the British government still tried to avoid civilian casualties. This ruled out a bombing attack by the RAF, which at the time did not possess the accuracy needed to destroy the dock without serious loss of civilian life.[7] The Special Operations Executive were approached to see if its agents could destroy the dock gates. They decided that the mission was beyond their capabilities because the weight of explosives required too many agents just to carry them.[8] The RN were also unable to mount an operation, as St Nazaire is 8 km (5 miles) up the Loire estuary. Any naval ships large enough to cause sufficient damage would be detected well before they were within range.[7] The planners then examined whether a commando force could be used. There was an unusually high spring tide due in March 1942, which would allow a light ship to pass over the sand banks in the estuary and approach the docks, bypassing the dredged and presumably well-defended channel. It would still be too shallow for infantry landing ships, but specially lightened destroyers might succeed.[9] Plan[edit source | editbeta]St Nazaire docks, 1942 The purpose of the raid was to destroy three objectives: the Normandie dock, the old gates into the Basin de St Nazaire together with the water pumping machinery and other installations, and any U-boats or other shipping in the area.[10] The initial Combined Operations plan required two specially lightened destroyers to carry out the raid. The first would be packed with explosives and rammed into the dock gates. Commandos on board would then disembark and use demolition charges to destroy nearby dock installations, searchlights and gun emplacements.[11] The destroyer would then be blown up, and the second ship would come in and evacuate the ship's crew and the commandos. At the same time the RAF would carry out a number of diversionary air raids in the area.[9] When the plan was presented to the Admiralty, they refused to support it. The certain loss of one or both destroyers to eliminate the dry dock was out of the question. They suggested they could provide an old Free French ship, the Ouragan and a flotilla of small motor launches to transport the commandos and evacuate them afterwards.[9] Approval for the mission, codenamed Operation Chariot, was given on 3 March 1942. Using a French ship would involve using the Free French forces and increase the number of people aware of the raid. Consequently it was decided the navy would have to provide a ship of their own. The RAF complained that the raid would draw heavily on their resources; the number of aircraft assigned by RAF Bomber Command was reduced time and again before the day of the raid. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill further complicated matters when he ordered that bombing should only take place if targets were clearly identified.[8] The St. Nazaire U-boat pens in 2005 Combined Operations Headquarters worked closely with several intelligence organisations to plan the raid. The Naval Intelligence Division compiled information from a variety of sources. A detailed plan of the town of St Nazaire was provided by the Secret Intelligence Service, and information on the coastal artillery nearby was sourced from the War Office's Military Intelligence branch. Intelligence about the dock itself came from pre-war technical journals. The RN's Operational Intelligence Centre selected the route and timing for the raid based on intelligence about the location of minefields and German recognition signals sourced from Enigma decrypts and knowledge of Luftwaffe patrols compiled by the Air Ministry's Air Intelligence Branch.[5]When all the plans had been pulled together and the timing worked out, the raid was expected to last no longer than two hours. The commandos and crew from Campbeltown would board the motor launches at the Old Mole jetty and then return to base.[12] Composition of the raiding force[edit source | editbeta]HMS Campbeltown being converted for the raid. There are twin lines of armour plate down each side of the ship and the Oerlikonmountings. Two of her funnels have been removed, with the remaining two cut at an angle The revised Combined Operations plan required one destroyer to ram the dock gates and a number of smaller craft to transport the Commandos. The Royal Navy would therefore provide the largest contingent for the raid, under the overall command of the senior naval officer, Commander Robert Ryder. The ship selected to ram into the dock gates was HMS Campbeltown, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Stephen Halden Beattie. TheCampbeltown was a First World War destroyer and had previously been the USS Buchanan in the United States Navy. She had come into RN service in 1940 as one of 50 destroyers transferred to the United Kingdom under the Destroyers for Bases Agreement.[12] Converting Campbeltown for the raid took ten days. She had to be lightened to raise her draught to get over the sand banks in the estuary. This was achieved by completely stripping all her internal compartments.[13] The dockyard removed her three 4 inch (100 mm) guns, torpedoes and depth charges from the deck and replaced the forward gun with a light quick–firing 12 pounder (3"). Eight 20 mm Oerlikons were installed on mountings raised above deck level.[14] The bridge and wheelhouse were given extra armour-plate protection, and two rows of armour were fixed along the sides of the ship to protect the Commandos on the open deck.[15] Two of her four funnels were removed, and the forward two were cut at an angle to resemble those of a German destroyer.[16] The bow was packed with 4.5 tons of high explosives, which were set in concrete.[13] It was decided that the explosive charge would be timed to detonate after the raiders had left the harbour. To prevent the Germans towing her away, the crew would open the ship's seacocks before abandoning the ship.[12] Should she become disabled or sunk before getting to the dock, four motor launches had been detailed to take off the crew and put the commandos ashore. The charge would be reset to explode after the last boat had left.[17] British Commandos, 1942 Other naval units involved were two Hunt class destroyers, HMS Tynedale and Atherstone, which would accompany the force to and from the French coast and remain out at sea during the raid.[12] A Motor Gun Boat (MGB 314) was the headquarters ship for the raid, with Commander Ryder and the commanding officer of the Commandos on board.[18] A Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB 74), commanded by Sub-Lieutenant Michael Wynn,[19] had two objectives: If the outer Normandie dock gates were open, she had to torpedo the inner dock gates. If the gates were closed she would instead torpedo the gates at the old entrance into the St Nazaire basin.[12] To assist in transporting the Commandos, 12 motor launches (ML) were assigned from the 20th and 28th Motor Launch flotillas. These boats were re-armed with two Oerlikon 20 mm guns mounted forward and aft to complement their twin Lewis guns.[20][nb 2] At the last minute another four MLs were assigned from the 7th Motor Launch flotilla (see Footnotes for flotilla details). These four boats were also armed with two torpedoes each. Instead of transporting the Commandos, these boats were to engage any German shipping found in the estuary.[11] All the MLs had a 500 gallon auxiliary fuel tank fixed to the upper deck to increase their range.[22] The S class submarine HMS Sturgeon would leave before the rest of the convoy and be in position to act as a navigational beacon to guide the convoy into the Loire estuary.[12] The man selected to lead the Commando force was Lieutenant Colonel Charles Newman; his own No. 2 Commando would provide the largest Commandos contingent, 173 men, for the raid.[12][18] The Special Service Brigade headquarters used the raid to provide experience for their other units and 92 men were drawn from Nos 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, and 12 Commandos.[18][23][24] The Commandos were divided into three groups; One and Two would travel in the MLs, three would be in the Campbeltown. Under the command of Captain Hodgeson, Group One had the objectives of securing the Old Mole and eliminating the anti-aircraft gun positions around the southern quays. They were then to move into the old town and blow up the power station, bridges and locks for the new entrance into the basin from the Avant port.[25] The capture of the mole was a major objective, as it was to be the embarkation point for the evacuation after the mission.[26] Group Two, under the command of Captain Burn, would land at the old entrance to the St Nazaire basin. Their objectives were to take out the anti-aircraft positions in the area and the German headquarters, to blow up the locks and bridges at the old entrance into the basin and then to guard against a counter-attack from the submarine base.[25] Group Three was under the command of Major William 'Bill' Copland, who was also the Commandos' second in command. They were to secure the immediate area around the Campbeltown, destroy the dock's water-pumping and gate-opening machinery and the nearby underground fuel tanks.[26] All three groups were subdivided into assault, demolition and protection teams. The assault teams would clear the way for the other two. The demolition teams carrying the explosive charges only had sidearms for self-defence; the protection teams, armed with Thompson submachine guns, were to defend them while they completed their tasks.[26] The Commandos were aided in their planning for the operation by Captain Bill Pritchard of the Royal Engineers, who had pre-war experience as an apprentice in the Great Western Railway dockyards and whose father was the dock master of Cardiff Docks. In 1940, while part of the British Expeditionary Force in France, his duties had included examining how to disable the French dockyards if they were captured. One of the dockyards he had studied was St Nazaire, and he had submitted a report detailing how to put the dock out of action.[24] German forces[edit source | editbeta]German 20 mm anti-aircraft gun The Germans had around 5,000 troops in the immediate area of St Nazaire.[27] The port was defended by the 280th Naval Artillery Battalion under the command of Kapitän zur See Edo Dieckmann. The battalion was composed of 28 guns of various calibres from 75 mm to 280 mm railway guns,[28] all positioned to guard the coastal approaches. The heavy guns were supplemented by the guns and searchlights of the 22nd Naval Flak Brigade[nb 3]under the command of Kapitän zur See Karl-Konrad Mecke. The brigade was equipped with 43 anti-aircraft guns ranging in calibre from 20 to 40 mm. These guns had a dual role as both anti-aircraft and coastal defence weapons. Many were in concrete emplacements on top of the submarine pens and other dockside installations of the St Nazaire submarine base.[28][29] The harbour defence companies were responsible for local defence and for the security of the ships and submarines moored in the harbour. These companies and the harbour defence boats used to patrol the river were under the command of Harbour Commander Korvettenkapitän Kellerman. The333rd Infantry Division was the German Army unit responsible for the defence of the coast between St Nazaire and Lorient. The division had no troops based in the town, but some were located in villages nearby and would be able to respond to any attack on the port.[30] The German Navy had at least three surface ships in the Loire estuary: a destroyer, an armed trawler and a Sperrbrecher (minesweeper), the latter being the guard ship for the port.[31] On the night of the raid there were also four harbour defence boats and ten ships from the 16th and 42nd Minesweeper flotillas berthed in the basin, while two tankers were berthed inside the Normandie dock.[28] The 6th and 7th U-Boat flotillas, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Georg-Wilhelm Schulz and Korvettenkapitän Herbert Sohler respectively, were permanently based in the port. It is not known how many submarines were present on the day of the raid. The submarine base had been inspected by the U-Boat Commander in Chief, Vizeadmiral Karl Dönitz, the day before the raid. He asked what would they do if the base was subject to an attack by British Commandos. Sohler replied that "an attack on the base would be hazardous and highly improbable".[32] The raid[edit source | editbeta]Outward journey[edit source | editbeta]The three destroyers and 16 small boats left Falmouth, Cornwall at 14:00 on 26 March 1942.[2] They formed into a convoy of three lanes, with the destroyers in the middle. On arrival at St Nazaire the portside MLs were to head for the Old Mole to disembark their Commandos, while the starboard lane would make for the old entrance to the basin to disembark theirs. Not having the range to reach St Nazaire unaided, the MTB and MGB were taken under tow by the Campbeltown and Atherstone.[26] On 27 March at 07:20 Tynedale reported a U-Boat on the surface and opened fire.[33] The two escort destroyers left the convoy to engage the U-Boat, later identified as U-593. The U-Boat promptly dived and was unsuccessfully attacked by depth charges. The two destroyers returned to the convoy at 09:00.[27] The convoy next encountered two French fishing trawlers. Both crews were taken off and the ships sunk for fear they might report the composition and location of the convoy.[27] At 17:00 the convoy received a signal from Commander-in-Chief Plymouth that five German torpedo boats were in the area. Two hours later another signal informed them that another two Hunt class destroyers, HMS Cleveland and HMS Brocklesby, had been dispatched at full speed to join the convoy.[34][nb 4] The convoy reached a position 65 nautical miles (120 km; 75 mi) off St Nazaire at 21:00 and changed course toward the estuary, leaving Atherstone and Tynedale as a sea patrol.[36] The convoy adopted a new formation with the MGB and two torpedo MLs in the lead, followed by Campbeltown. The rest of the MLs formed two columns on either side and astern of the destroyer, with the MTB bringing up the rear.[37] The first casualty of the raid was ML 341, which had developed engine trouble and was abandoned. At 22:00 the submarine Sturgeon directed her navigation beacon out to sea to guide the convoy in. At about the same time the Campbeltown raised the German naval ensign in an attempt to deceive any German lookouts into thinking she was a German destroyer.[27] At 23:30 on 27 March, five RAF squadrons (comprising 35 Whitleys and 27 Wellingtons) started their bombing runs. The bombers had to stay above 6,000 feet (1,800 m) and were supposed to remain over the port for 60 minutes to divert attention toward themselves and away from the sea. They had orders to only bomb clearly identified military targets and to drop only one bomb at a time. As it turned out, poor weather over the port (10/10ths cloud) meant that only four aircraft bombed targets in St Nazaire. Six aircraft managed to bomb other nearby targets.[27][38] The unusual behaviour of the bombers concerned Kapitän zur See Mecke. At 00:00 on 28 March, he issued a warning that there might be a parachute landing in progress. At 01:00 on 28 March, he followed up by ordering all guns to cease firing and searchlights to be extinguished in case the bombers were using them to locate the port. Everyone was placed on a heightened state of alert. The harbour defence companies and ships' crews were ordered out of the air raid shelters. During all this a lookout reported seeing some activity out at sea, so Mecke began suspecting some type of landing and ordered extra attention to be paid to the approaches to the harbour.[39] The run-in[edit source | editbeta]HMS Campbeltown wedged in the dock gates. Note the exposed forward gun position on Campbeltown and the German anti-aircraft gun position on the roof of the building at the rear At 00:30 hours on 28 March the convoy crossed over the shoals at the mouth of the Loire estuary, with the Campbeltown scraping the bottom twice. Each time she was able to pull free, and the group proceeded on up toward the harbor in darkness. They had got to within about eight minutes passage from the dock gates when at 01:22 the entire convoy was illuminated by the combined searchlights of both banks of the estuary. A naval signal light demanded their identification.[31] The MGB-314 replied in a coded response obtained from a German trawler boarded during the Vagsoy mission. A few bursts were fired from a shore battery and both the Campbeltown and the MGB-314 replied: "Ship being fired upon by friendly forces" The deception gave them a couple more precious minutes before every German gun in the bay opened fire.[40] At 01:28, with the convoy a 1 mile (1.6 km) from the dock gates, Beattie ordered the German flag lowered and the White Ensign raised. The intensity of the German fire seemed to increase. The guard ship opened fire but was quickly silenced when the ships in the convoy responded, shooting into her as they passed.[41] By now all the ships in the convoy were within range to engage targets ashore and were firing at the gun emplacements and searchlights. Campbeltown was hit a number of times but still increased her speed to 19 kn (35 km/h). The helmsman on her bridge was killed; his replacement was wounded and replaced as well.[42] Blinded by the searchlights, Beattie knew they were close to their objective. Still under heavy fire, the MGB turned into the estuary as the Campbeltown cleared the end of the Old Mole, cut through anti-torpedo netting strung across the entrance and rammed the dock gates, striking home at 01:34, three minutes later than scheduled. The force of the impact drove the ship 33 feet (10 m) onto the gates.[31] Disembarkation from the Campbeltown and the MLs[edit source | editbeta]Commando prisoners under German escort The Commandos on Campbeltown now disembarked: two assault teams, five demolition teams with their protectors and a mortar group.[37] Three demolition teams were tasked with destroying the dock pumping machinery and other installations associated with the drydock. The kilt wearing Captain Donald Roy - 'The Laird' and his 14 man assault troop were tasked with taking out two pump-house roof-top gun emplacements high above the quayside and securing a bridge to provide a route for the raiding parties to exit the dock area. Roy and Sgt Don Randall used scaling ladders and grenades to accomplish the former and a head on rush to secure the bridge and form a bridgehead that enabled Capt. Bob Montgomery and Lt Corran Purdon and their demolition teams to exit the area.[43][44] They lost 4 men in this action. The fifth team also succeeded in completing all their objectives but almost half its men were killed. The other two Commando groups were not as successful. The MLs transporting Groups One and Two had almost all been destroyed on their approach. ML 457 was the only boat to land its Commandos on the Old Mole and only ML 177 had managed to reach the gates at the old entrance to the basin.[45] That team succeeded in planting charges on two tugboats moored in the basin.[46] There were only two other MLs in the vicinity: ML 160 had continued past the dock and was engaging targets upriver, ML 269 appeared to be out of control and was running in circles. By this time the crew of Campbeltown had detonated the scuttling charges and gathered at the rear of the ship to be taken off. ML 177 came alongside the destroyer and took 30 men on board including Beattie and some of the wounded. Major Copland went through Campbeltownand evacuated the wounded towards the Old Mole, not knowing that there were no other boats there to take the Commandos off.[45] Lt Col Newman aboard the MGB, need not have landed, but he was one of the first ashore. One of his first actions was to direct mortar fire onto a gun position on top of the submarine pens that was causing heavy casualties among the Commandos. He next directed machine-gun fire onto an armed trawler, which was forced to withdraw upriver. Newman organised a defence that succeeded in keeping the increasing numbers of German reinforcements at bay until the demolition parties had completed their tasks.[47] Some 100 Commandos were still ashore when Newman realised that evacuation by sea was no longer an option. He gathered the survivors and issued three orders:

Newman and Copland led the charge from the old town across a bridge raked by machine gun fire and advanced into the new town. The Commandos attempted to get through the narrow streets of the town and into the surrounding countryside, but were eventually surrounded. When their ammunition was expended their only option was to surrender.[45][47][49] Not all the Commandos were captured; five men reached neutral Spain, from where they eventually returned to England.[50] Small ships[edit source | editbeta]Most of the MLs had been destroyed on the run in and were burning. The first ML in the starboard column was the first boat to catch fire; her captain managed to beach her at the end of the Old Mole. Some starboard boats managed to reach their objective and disembark their Commandos. ML 443, the leading boat in the port column, got to within 10 feet (3.0 m) of the mole in the face of heavy direct fire and hand grenades before being set on fire. The crew were rescued by ML 160, one of the torpedo MLs which had been looking for targets of opportunity such as the two large tankers reported to be in the harbour.[51] The commanders of MLs 160 and 443, Lieutenants T Boyd and T D L Platt, were awarded the Distinguished Service Order for their bravery.[52][nb 5] The rest of the port column had been destroyed or disabled before reaching the mole.[54] MLs 192 and 262 were set on fire; there were only six survivors. ML 268 was blown up; one man survived.[55] ML 177, the launch that had successfully taken off some of the crew fromCampbeltown, was sunk on her way out of the estuary.[56] ML 269, another torpedo-armed boat, had the unenviable task of moving up and down the river at high speed to draw German fire away from the landings. Soon after passing Campbeltown it was hit and its steering damaged. It took ten minutes to repair the steering. They turned and started in the other direction, opening fire on an armed trawler in passing. Return fire from the trawler set their engine on fire.[57] The German torpedo boat Jaguar ML 306 also came under heavy fire when it arrived near the port. Sergeant Thomas Durrant of No. 1 Commando, manning the aft Lewis gun, engaged gun and searchlight positions on the run in. He was wounded but refused to leave the gun for treatment. The ML reached the open sea but was attacked at short range by the German torpedo boat Jaguar. Durrant returned fire, aiming for the torpedo boat's bridge. He was wounded again but remained at his gun even after the German commander asked for their surrender. Firing drum after drum of ammunition, he refused to give up until after the ML had been boarded. Durrant died of his wounds and, after the recommendation of the Jaguar's commander, was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.[34][58] After the Commando headquarters group had landed, Commander Ryder went to check for himself that Campbeltown was firmly stuck in the dock. Some of her surviving crewmen were being taken on board the MGB. Ryder returned to the boat and ordered the MTB to carry out its alternative task and torpedo the lock gates at the old entrance to the basin. After a successful torpedo attack, Ryder ordered the MTB to leave. On their way out of the estuary they stopped to collect survivors from a sinking ML and were hit and set on fire.[59] Back at the docks the MGB had positioned itself in mid-river to engage enemy gun emplacements. The forward 2 pounder was manned by Able Seaman William Alfred Savage. Commander Ryder reported that

Motor Gun Boat 314 Ryder could see no ships other than seven or eight burning MLs. He then realised that the landing places at the Old Mole and the entrance to the basin had both been recaptured by the Germans.[2] There was nothing more they could do for the Commandos, so they headed out to sea. On their way they were continuously illuminated by German searchlights and were hit at least six times by the German guns. Passing ML 270, they ordered her to follow and made smoke to hide both boats. When they reached the open sea the smaller calibre guns were out of range and stopped firing but the heavier artillery continued to engage them. The boats were about 4 miles (6.4 km) off-shore when the last German salvo straddled them and killed Savage, who was still at his gun. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his exploits. His citation recognised both Savage and the bravery of "the many unnamed crews of the Motor Gun Boat, Motor Torpedo Boat and Motor Launches who continued to carry out their duties in exposed positions, in the face of close range enemy fire."[52] Return journey[edit source | editbeta]The remains of an unidentified Motor Launch, 28 March 1942 At 06:30 the five German torpedo boats that the convoy had evaded the previous day were sighted by HMS Atherstone and Tynedale. The two destroyers turned toward them and opened fire at a range of 7 miles (11 km). After ten minutes the German boats turned away, making smoke.[60] The destroyers sighted the MGB and two accompanying MLs soon after and transferred their casualties to the Atherstone. Not expecting any more boats to arrive, they headed for home. Just after 09:00 the destroyers Brocklesby and Cleveland arrived, sent by Commander-in-Chief Plymouth. Shortly after this the ships were spotted by a Heinkel 115 floatplane of the Luftwaffe.[2] The next aircraft on the scene, a Junkers 88, was engaged by a RAF Bristol Beaufighter which had appeared in the area earlier. Both machines crashed into the sea. Other German planes arrived but were driven off by Beaufighters and Hudsons from Coastal Command. The Atlantic weather conditions deteriorated. Amid concerns about the growing German threat and the realisation that the damaged small ships would not be able to keep up, Commander Sayer ordered the crews off the smaller boats and had them sunk.[61] Three of the small vessels managed to return to England: MLs 160, 307 and 443.[62] They had reached the rendezvous and waited until 10:00 for the destroyers to appear. Having already been attacked once, they moved further out into the Atlantic to try and avoid the German Air Force, but a Junkers 88 appeared overhead at 07:30 and approached them at low level for a closer look. The ships opened fire and hit the Junkers in the cockpit. The plane went into the sea. The next aircraft to appear was a Blohm and Voss seaplane which attempted to bomb the ships, but left after being damaged by machine-gun fire. The surviving MLs eventually reached England unaided the following day.[63] Campbeltown explodes[edit source | editbeta]Close up of HMS Campbeltown after the raid. Note the shell damage in the hull and upper works and the German personnel on–board the vessel The explosive charges in HMS Campbeltown detonated at noon on 28 March 1942, the dry dock was destroyed.[64] Both tankers that were in the dock were swept away by the wall of water and sunk,[65] (or just swept to the far end of the Dock, but not sunk).[66] A party of 40 senior German officers and civilians who were on a tour of the ship were killed. In total, the explosion killed about 360 men.[67] The wreck of the Campbeltown could still be seen inside the dry dock months later when RAF photo reconnaissance planes were sent to photograph the port.[68] The day after the explosion, Organisation Todt workers were assigned to clean up the debris and wreckage. On 30 March at 16:30 the torpedoes from MTB 74, which were on a delayed fuse setting, exploded at the old entrance into the basin. This raised alarms among the Germans. The Organisation Todt workers ran away from the dock area. German guards, mistaking their khaki uniforms for British uniforms, opened fire, killing some of them. The Germans also thought that some Commandos were still hiding in the town, and made a street by street search, during which some townspeople were also killed.[64] Aftermath[edit source | editbeta]Surviving British commandos, mission completed, are taken into captivity The Normandie Dock months after the raid. The wreck of HMS Campbeltown is dwarfed by the size of the dock. he explosion put the dry dock out of commission until the end of the war.[69] The St Nazaire raid had been a success, but at a cost. Of the 622 men of the Royal Navy and Commandos who took part in the raid, only 228 men returned to England. Five escaped overland via Spain and Gibraltar. 169 men were killed (105 RN and 64 Commandos) and another 215 became prisoners of war (106 RN and 109 Commandos). They were first taken to La Baule and then sent to Stalag 133 at Rennes.[13][49] The fallen British raiders were buried at the Escoublac-la-Baule cemetery with military honors. The cemetery is located 13 kilometres west of St Nazaire. To recognise their achievement, 89 decorations were awarded for the raid. This total includes the five Victoria Crosses awarded to Lieutenant Commander Beattie, Lieutenant Colonel Newman and Commander Ryder, and posthumous awards to Sergeant Durrant and Able Seaman Savage. Other decorations awarded were four Distinguished Service Orders, four Conspicuous Gallantry Medals, five Distinguished Conduct Medals, 17 Distinguished Service Crosses, 11 Military Crosses, 24 Distinguished Service Medals and 15Military Medals. Four men were awarded the Croix de Guerre by France, another 51 were mentioned in dispatches

The number of Free French troops grew with Allied success in North Africa and subsequent rallying of the Army of Africa which pursued the fight against the Axis fighting in many campaigns and eventually invading Italy, occupied France and Germany from 1944 to 1945. On 23 October 1944, Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union officially recognized de Gaulle's regime as the provisional government of France (GPRF) which replaced the in-exile French State (relocated at Sigmarigen, a short-living City State in western Germany) and preceded the Fourth Republic (1946). Recruitment in liberated France led to notable enlargements of the French armies. By the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, France had 1,250,000 troops, 10 divisions of which were fighting in Germany. An expeditionary corps was created to liberate French Indochina then occupied by the Japanese. During the course of the war, French military losses totaled 212,000 dead, of which 92,000 were killed through the end of the campaign of 1940, 58,000 from 1940 to 1945 in other campaigns, 24,000 lost while serving in the French resistance, and a further 38,000 lost while serving with the German Army.[1] Among the odd aspects of French military history in the war were limited French participation in the Normandy beach landings of June 1944 (Free French SAS of Major Philippe Kieffer) and the presence of French SS among the defenders of Berlin in May 1945 (33rd SS Division commanded by Hauptsturmführer Henri Fenet).

German strategy Hitler had always fostered dreams about major military campaigns to defeat the Western European nations as a preliminary step to the conquest of territory in Eastern Europe, thus avoiding a two-front war. However, these intentions were absent from Führer-Directive N°6.[13] This plan was firmly based on the seemingly more realistic assumption that Germany's military strength would still have to be built up for several more years and that for the moment only limited objectives could be envisaged. They were aimed at improving Germany's ability to survive a long, protracted war in the West.[14] Hitler ordered a conquest of the Low Countries to be executed at the shortest possible notice. This would stop France from occupying them first, and prevent Allied air power from threatening the vital German Ruhr Area.[15] It would also provide the basis for a successful long-term air and sea campaign against Britain. There was no mention in the Führer-Directive of any immediate consecutive attack to conquer the whole of France, although as much as possible of the border areas in northern France should be occupied.[13] While writing the directive, Hitler had assumed that such an attack could be initiated within a period of at most a few weeks, but the very day he issued it he was disabused of this illusion. It transpired that he had been misinformed about the true state of Germany's forces. The motorized units had to recover, repairing the damage to their vehicles incurred in the Polish campaign, and ammunition stocks were largely depleted.[16] [edit] Similarity to Schlieffen PlanOn 10 October 1939, the British refused Hitler's offer of peace; on 12 October, the French did the same. Franz Halder, the chief of staff of the German Army (Generalstabschef des Heeres), presented the first plan for Fall Gelb ("Case Yellow") on 19 October, the pre-war codename of plans for campaigns in the Low Countries: the Aufmarschanweisung N°1, Fall Gelb ("Deployment Instruction No. 1, Case Yellow"). Halder's plan has often been compared to the Schlieffen Plan, which the Germans attempted to execute in 1914 during the opening phase of the First World War.[17] It was similar in that both plans entailed an advance through the middle of Belgium, but while the intention of the Schlieffen Plan was to gain a decisive victory by executing a surprise encirclement of the French Army, Aufmarschanweisung N°1 was based on an unimaginative frontal attack, sacrificing a projected half a million German soldiers to attain the limited goal of throwing the Allies back to the River Somme. Germany's strength for 1940 would then be spent; only in 1942 could the main attack against France begin.[18] Hitler was very disappointed with Halder's plan and reacted first by deciding that the German army should attack early, ready or not, in the hope that Allied unpreparedness might bring about an easy victory. This led to a series of postponements, as time and again commanders convinced Hitler to delay the attack for a few days or weeks to remedy some critical defect in the preparations, or to wait for better weather. Hitler also tried to alter the plan which he found unsatisfactory, without clearly understanding how it could be improved. This mainly resulted in a dispersion of effort, since besides the main axis in central Belgium, secondary attacks were foreseen further south. Hitler made such a suggestion on 11 November.[19] On 29 October, Halder let a second operational plan, Aufmarschanweisung N°2, Fall Gelb, reflect these changes by featuring a secondary attack on the Netherlands.[20] Hitler was not alone in disliking Halder's plan. General Gerd von Rundstedt, the commander of Army Group A, also disagreed with it. Unlike Hitler, von Rundstedt understood perfectly well how it should be rectified as a professional soldier. Its fundamental flaw was that it did not conform to the classic principles of the Bewegungskrieg ("manoeuvre warfare") which had been the basis of German operations since the 19th century. A breakthrough would have to be accomplished that would result in the encirclement and destruction of the main body of Allied forces. The logical place to achieve this would be in the region of Sedan, which lay in the sector of von Rundstedt's Army Group. On 21 October, von Rundstedt agreed with his chief of staff, Generalleutnant Erich von Manstein, that an alternative operational plan had to be arranged that would reflect these basic ideas, making Army Group A as strong as possible at the expense of Army Group B to the north.[21] [edit] Manstein PlanFurther information: Manstein Plan The evolution of German plans for Fall Gelb, the invasion of the Low Countries. The series begins at the left upper corner. Whilst von Manstein was formulating new plans in Koblenz, Generalleutnant Heinz Guderian, commander of the XIX Army Corps, Germany's elite armoured formation, happened to be lodged in a nearby hotel.[22] At this moment, von Manstein's plan consisted of a move directly north from Sedan against the rear of the main Allied forces in Belgium. When Guderian was invited to contribute to the plan during informal discussions, he proposed a radical and novel idea.[20] Not only his army corps, but most of the Panzerwaffe should be concentrated at Sedan. This concentration of armour should subsequently not move to the north but to the west, to execute a swift, deep, independent strategic penetration towards the English Channel without waiting for the main body of infantry divisions. This might lead to a strategic collapse of the enemy, avoiding the relatively high number of casualties normally caused by a Kesselschlacht ("annihilation battle"). Such a risky independent use of armour had been widely discussed in Germany before the war but had not been accepted as received doctrine. The German General Staff, however, doubted such an operation could work.[23] Von Manstein's operational idea won immediate support from Guderian. Guderian understood the terrain, having experienced the conditions with the German Army in 1914 and 1918.[24] Von Manstein wrote his first memorandum outlining the alternative plan on 31 October. In it he carefully avoided mentioning Guderian's name and downplayed the strategic part of the armoured units, in order to not generate unnecessary resistance.[25] Six more memoranda followed between 31 October 1939 and 12 January 1940, each becoming more radical in outline. All were rejected by the OKH, the German Army's headquarters, and nothing of their content reached Hitler.[24] [edit] Mechelen IncidentOn 10 January, a German Messerschmitt Bf 108 made a forced landing at Maasmechelen, north of Maastricht, in Belgium (the so-called "Mechelen Incident"). Among the occupants of the aircraft was Luftwaffe Major Hellmuth Reinberger, who was carrying a copy of the latest version of Aufmarschanweisung N°2. Reinberger was unable to destroy the documents, which quickly fell into the hands of the Belgian intelligence services.[26] It has often been suggested that this incident was the cause of a drastic change in German plans, but this is incorrect; in fact, a reformulation of them on 30 January, Aufmarschanweisung N°3, Fall Gelb, conformed to the earlier versions.[27] [edit] Adoption of Manstein PlanOn 27 January, von Manstein was relieved of his appointment as Chief of Staff of Army Group A and appointed commander of an army corps in Prussia, to begin his command in Stettin on 9 February, a move instigated by Halder to reduce von Manstein's influence.[28] Von Manstein's indignant staff brought his case to Hitler's attention. Hitler had, without any knowledge of von Manstein's plan, suggested an attack focused at Sedan but had been persuaded to forget the idea as it was too risky. On 2 February, von Manstein's plan was brought to his attention. On 17 February, Hitler summoned von Manstein, Generals Rudolf Schmundt (the German Army's Chief of Personnel) and Alfred Jodl, the Chief of Operations at the OKW (the German armed forces' supreme command), to attend a conference. Hitler sat and listened, abandoning his habits of interrupting and launching into monologues. In the end, he agreed to all of von Manstein's suggestions.[29] The next day, he ordered the plans to be changed in accordance with von Manstein's ideas. They appealed to Hitler mainly because they offered some real hope of victory.[30] Hitler recognized the breakthrough at Sedan only in tactical terms, whereas von Manstein saw it as a means to an end. He envisaged an operation to the English Channel and the encirclement of the Allied armies in Belgium, which, if carried out correctly, could have a favourable strategic outcome.[31][32] Halder had no intention of deviating from established doctrine by allowing an independent strategic penetration by the seven armoured divisions of Army Group A.[33] Much to the outrage of Guderian, this element was at first completely removed from the new plan, Aufmarschanweisung N°4, Fall Gelb, issued on 24 February.[20] However, Halder went through an "astonishing change of opinion".[34] Halder was criticized in the same way he had attacked von Manstein when he first suggested it. The bulk of the German officer corps was appalled by the plan, and they called him the "gravedigger of the Panzer force".[35] Even when adapted to more conventional methods, the new plan provoked a storm of protest from the majority of German generals. They thought it utterly irresponsible to create a concentration of forces in a position where they could not possibly be sufficiently supplied, while such inadequate supply routes as there were could easily be cut off by the French. If the Allies did not react as expected, the German offensive could end in catastrophe.[36] Their objections were ignored. Halder argued that, as Germany's strategic position seemed hopeless anyway, even the slightest chance of a decisive victory outweighed the certainty of ultimate defeat implied by inaction.[37] [edit] BlitzkriegMain article: Blitzkrieg The strategy, operational methods and tactics of the German Army and Luftwaffe has often been labelled "Blitzkrieg" (Lightning War). The concept is deeply controversial and is connected to the problem of the precise nature and origin of "Blitzkrieg" operations, of which the 1940 campaign is often described as a classic example. An essential element of "Blitzkrieg" was considered to be a strategic, or series of operational developments, executed by mechanised forces which led to the total collapse of the defenders' armed forces. "Blitzkrieg" has also been looked on as a revolutionary form of warfare. In recent years, its novelty and even its very existence have been disputed.[38][39] Rapid and decisive victories had been pursued by armies well before the Second World War. In the German wars of unification and First World War campaigns, the German General Staff had attempted Bewegungskrieg (Movement War), similar to the modern perception of "Blitzkrieg", with varying degrees of success. During the First World War, these methods often succeeded in achieving tactical breakthroughs, but the operational exploitation took time as armies lacked motorisation, could not move quickly, and sometimes failed to achieve a decisive victory altogether. The development of tanks, aircraft, and more importantly, motorised infantry and artillery, enabled the Germans to implement these old methods again with new technology in 1940. The combustion engine solved the problem of operational level exploitation.[40] When dealing with "Blitzkrieg" as a concept, things become complicated. It is seen as an anomaly and there is no explicit reference to such strategy, operations or tactics in the German battle plans. There is no evidence in German military art, strategy or industrial preparation that points to the existence of a thought out "Blitzkrieg" tendency.[41][42] Evidence suggests that the German Reich was preparing for a long sustained war of attrition, not a quick war of manoeuvre. Hitler's miscalculations in 1939 forced him into war before he was ready, and under these circumstances the German General Staff reverted to attempting to win a quick war, before the economic and material superiority of the Allies could make a difference, although this was not their original intention.[43] It was only after the defeat of France in 1940, that the German military pursued a "Blitzkrieg"-kind of warfare to achieve its ambitions in Europe. German historian Karl-Heinz Frieser explained: